Disclaimer: This is a post about going to the doctor in America, why it sucks, and a way to make it better. It’s also a post about my wife’s startup. Which means I’m almost certainly biased on this topic. But also I really think these things. I wouldn’t say things on WBW if I didn’t really think them, because that would be a dick thing to do. But I’m also not exactly a neutral observer on this one. But still. K? K.

___________

There’s someone I’d like you to meet.

This my wife, Tandice. We met back in 2011.

It took a while but I eventually won her over, and we’ve been together ever since.

No problem.

Anyway, one of the things about Tandice is that she’s kind of Larry-David-esque, and she likes to complain about stuff.

Her most impassioned complaints are reserved for one particular type of experience: the doctor’s office.

Tandice has a rare autoimmune disease that, without some very novel treatments, would cause her immune system to attack her eyes and destroy her vision. This, plus some general hypochondria, has made her somewhat of a regular at the doctor’s office.

The frustrations start with making the appointment.

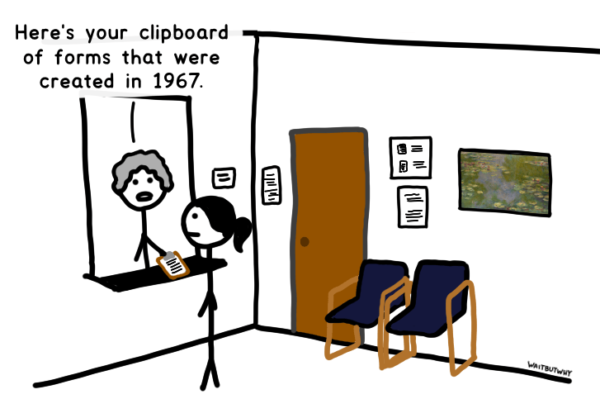

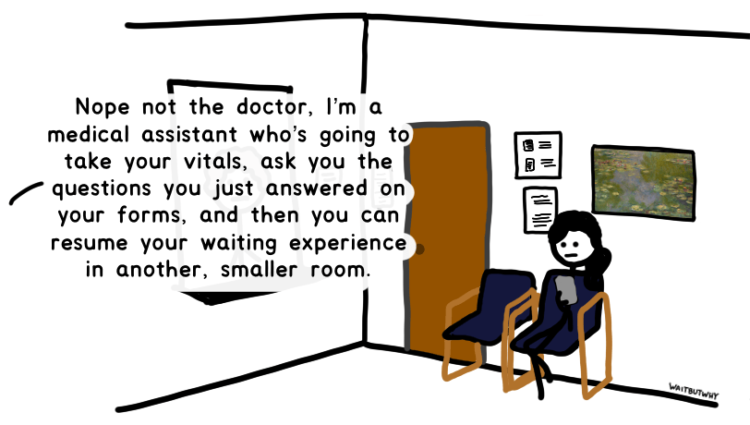

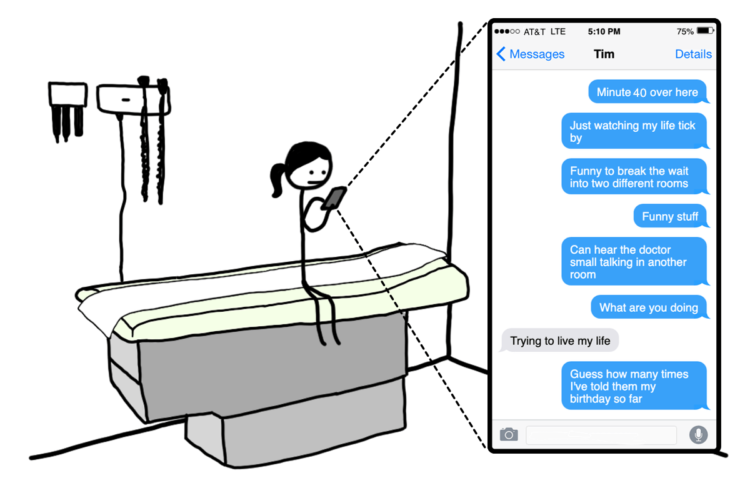

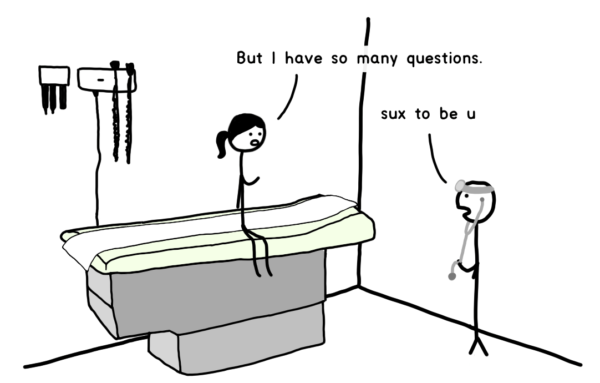

Then comes the actual appointment.

Over the years, Tandice’s complaints have turned into curiosity. Why, in 2021, in the U.S., would going to the doctor be so shitty?

Why going to the doctor sucks

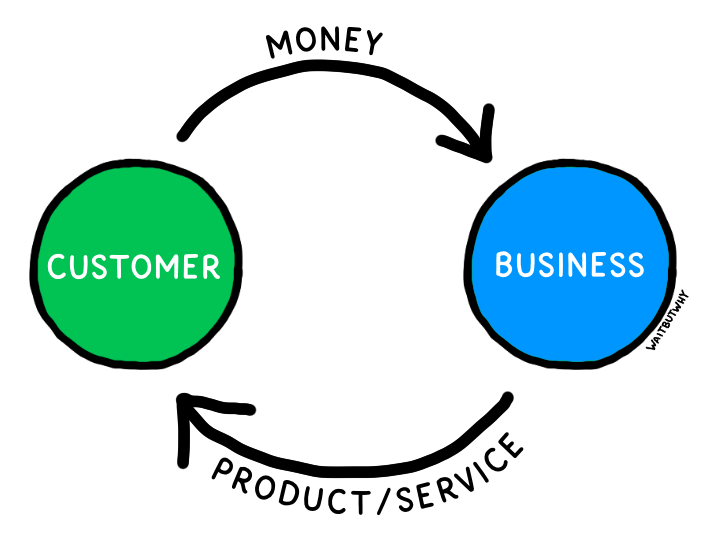

So you know how the free market looks kind of like this?

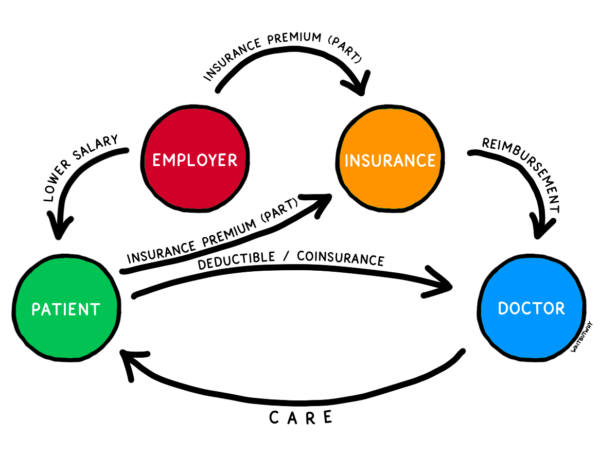

Well the U.S. healthcare industry looks more like this:1

What the hell?

It definitely isn’t a single-payer system—but as investor Bill Gurley explains, it’s not a free market system either:

There is no price evaluation during the purchase. The person paying is not the person consuming the service, and the majority of choices are made without comparative options. In many ways, we have the worst of both worlds. Our system … has the illusion of a free market and the illusion of regulated market with the apparent benefit of neither.1

Car insurance makes sense, because a car accident can happen to anyone, anytime, and the resulting damages and liability could leave the driver on the hook for tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars, something very few people can afford. The same logic applies to catastrophic coverage in health. For bearing the cost of an unexpected ambulance, injury, cancer treatment, etc., insurance is a good system.

But if the auto industry were like the healthcare industry, your employer2 would be incentivized to swap out some of your salary with auto coverage of their choice. When it was time for an oil change, you’d have to look for “in-network” auto shops. I’m glad that’s not how the auto industry works.

I’m not sure what exactly I think the U.S. healthcare system should look like—but I’m pretty sure it shouldn’t look like this. Maybe one day the system will change, but rather than hold our breath for that, let’s talk about one aspect of the system we can do something about: going to the doctor.

The beauty of a basic free market interaction—at, say, a local barber—is that the business and customer incentives are entirely aligned. To get more of what it wants (revenue), the barbershop needs loyal customers—something that only happens when people have a good experience at the shop and leave with a haircut they like, at a price they think is reasonable.

But the convoluted U.S. healthcare system screws up that alignment. Sure, doctors get paid when patients choose to use their services, but there are two middlemen who distort that relationship, as a majority of the doctor’s actual payment comes from the insurer (who also negotiates the prices), and the insurer gets a majority of its payments from the employer.3 The patient is so far removed from the doctor, financially, that the various prices for the doctor’s services aren’t even available to the patient—they’re treated more like proprietary back-office info that’s none of the patient’s business. While there’s still some element of consumer choice and competition, the typical patient’s limited in-network options and the lack of transparency when comparing those options significantly dilutes this powerful motivator. Mostly, the system’s fee-for-service model incentivizes doctors to see a high volume of patients, even if it comes at the expense of quality.

American patients aren’t treated like customers because they’re not customers. Once you consider this, the typical4 American patient’s experience makes much more sense. The wait time for an appointment (24 days on average in the U.S.) and the inconvenient open hours. The lack of basic modern conveniences (I make my haircut appointments online but have to call the doctor’s office and listen to hold music). The stereotypically long waits on the day of the appointment (often because many doctors book two patients for every time slot). The lack of any follow-up after an appointment or any sophisticated way for patients to access their history and analyze trends.5

All of this feels a whole lot like the experience we have at places like the DMV or the post office—places where there’s little practical incentive to provide good customer service. It’s also probably why so many Americans put a doctor’s visit into the same bucket as a trip to the DMV or the post office: something to avoid if at all possible.

In a world where every decade raises our expectations for ease and convenience, it’s no surprise that people, especially young people,6 are going to the doctor less and less.

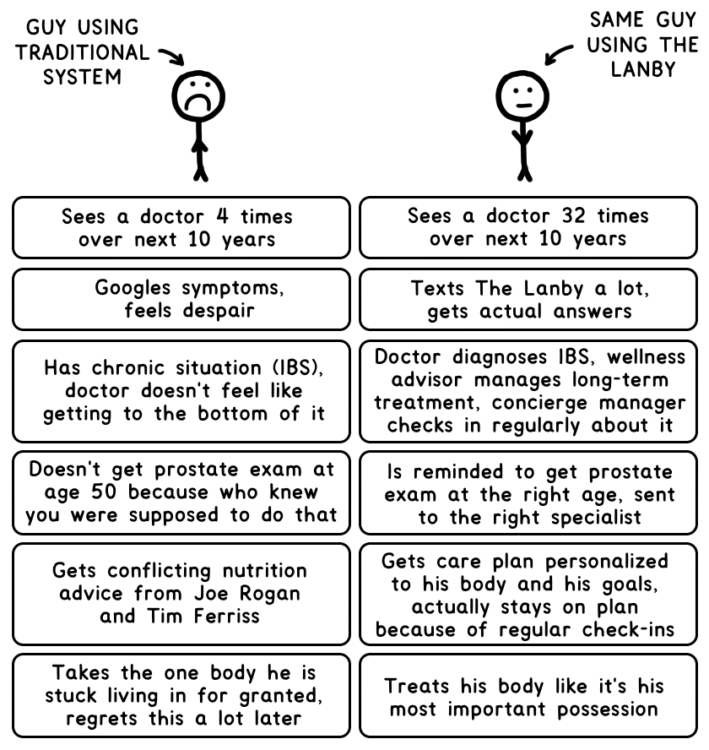

Count me among them. My last doctor’s appointment—a typical experience that was unpleasant and mostly unhelpful—was four years ago. I’ve since replaced the doctor with four things:

1) Ignoring my health and hoping for the best

2) Asking Google questions

3) Asking my doctor friends questions

4) Visiting urgent care clinics7

This is obviously not a great plan. Whether you’re a “me” kind of patient or a Tandice kind of patient, or somewhere in between, there’s a good chance you’re not getting what you need from the healthcare system.

And it was just as Tandice was starting to wonder if she might be able to do something about all this that she met Chloe.

They were introduced through a mutual friend who thought they might have a lot to talk about. Chloe was a breast cancer survivor who, after having to navigate the system at such a young age, from treatment to specialist coordination to post-survivorship care, was also fixated on the problem of being a patient. They got together to discuss.

Tandice came home electrified. She and Chloe were going to build the doctor’s office they wished they could go to. They decided to call it The Lanby.

The Lanby

Tandice and Chloe spent the next six months researching, brainstorming, planning, white boarding, flow charting, spreadsheeting, and generally organizing their list of patient complaints.

The first question they had to answer was, “Is there some good reason healthcare has to suck like this? There’s gotta be some reason it’s like this, right?” The answer turned out to be, “Actually, not really.”

The second question was, “Where do we start?” They knew they couldn’t overhaul the whole system, so they decided to focus on their own experience and what they wish they had most during their patient journeys: one centralized healthcare home base. This, they believed, should be the role of primary care.

From there, the natural third question: “What could great primary care look like if it were designed purely from the patient’s perspective? What would be our dream experience as a patient?”

Reasoning from first principles, they started to lay down what they believed should be the core features of great primary care:

Easy. Friction should be minimized at every step of the way.

Unlimited. A primary care physician isn’t just another specialist. Primary care should be both the patient’s first line of defense and their long-term partner. The exact kind of thing that’s best as a flat-fee, unlimited-use model—something patients are incentivized to interact with as often as they want to or need to.

Financially simple. A single annual membership fee and that’s it. No middlemen or extra costs. Likewise on the doctor’s side: a flat, annual salary that, unlike the fee-for-service model, incentivizes quality over volume.

Comprehensive. True primary care should focus on all facets of a patient’s health, not just medical health.

Continuous. To facilitate a long-term partnership, patients should be seen by the same practitioners every visit. Continuity should also extend to specialist referrals. Primary care should be the patient’s hub, making the referral, communicating with the specialist, and closing the loop after the treatment.

Common sense-y. When in doubt, go with common sense. Example: Some patients prefer to exclusively see the doctor in person. Some would like to go entirely virtual. But common sense suggests that most would like a mix, depending on the reason for the visit.

Patient-centric. Every single decision should be run through the “what would this be like for the patient?” lens.

With those as the building blocks, they designed something they believed could nail every important point: a primary care member’s club.

The basic framework: Members pay $3,000/year ($2,000 right now, more on that below) and have unlimited visits, both in person and virtually. It’s a no-insurance model, though members should still carry basic insurance (to cover catastrophic care, specialist visits, labwork, and prescriptions). This keeps insurance confined to the places where insurance makes sense and lets patients be actual customers where that makes sense.8

Tandice and Chloe imagined themselves joining this kind of members club, and brainstormed what it would have to be like to absolutely delight them. They concluded that there were really two realms to great primary care: the care itself, and everything about the patient experience surrounding that care (“delivery”). Here’s their plan for each:

1) Care

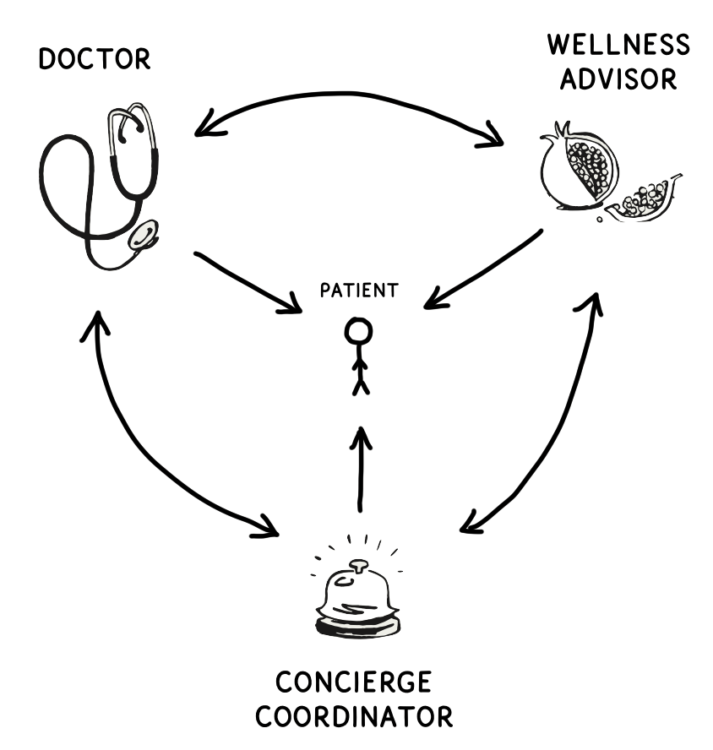

Thinking about primary care from first principles yielded an interesting insight: primary care should ideally be handled by three practitioners, not just a single doctor. If The Lanby was really going to live up to its promise and cover every aspect of a patient’s basic health, each member should be assigned to a three-person team that worked together to provide comprehensive, continuous, and coordinated care. Here’s how it looks:

The doctor is the kind they wish they had: Someone curious, patient, and empathetic. Someone with a wide breadth of knowledge and lifelong learner who’s always up on the latest research.

The wellness advisor takes on everything about your health that’s outside of the doctor’s direct purview: nutrition, exercise, sleep, etc. Is Whole 30 the right kind of diet for me? Do air purifiers actually do anything? Is a Fitbit the best health tracker? The wellness advisor’s got you.

The concierge manager is a registered nurse and your go-to contact—someone you can text anytime about anything health-related. Basically how you’d treat your parent if they happened to be a medical professional.

A Lanby member can know that somewhere out there, a group of pros is obsessed with their health and has it covered—in both a short- and long-term sense.

2) Delivery

Delivery is the hidden beast at the heart of good (or awful) healthcare. If we imagine the consumer experience as a spectrum, The Lanby’s goal is to take healthcare delivery from Point A to Point C.

Going from A to B is simple: treat the patient like a customer and bring the systems from the 1960s into the 2020s. At Point B, appointments are easy to make, for sometime soon, and they actually last long enough for all the patient’s questions. Patient data is collected and easy to access online, where patients can also order refills and chat with the team. Point B means making everything in the Tandice-at-the-doctor comic good/easy/modern/effective instead of bad/hard/archaic/useless. An analysis of 35,000 online reviews revealed that 96% of patient complaints are about customer service. Getting to Point B should take care of that.

Going from Point B to Point C takes things to the next level with a new concept: healthcare hospitality.

Healthcare hospitality means that everything is nice. The space looks great and smells great and the seats are super comfortable. When you walk in, you’re offered a cup of coffee. There’s a bookshelf full of health-related books you can check out, old school library-style. There will never be a clipboard of forms because handing a customer a clipboard is the opposite of hospitality. Cozy robes instead of paper gowns. Charmin instead of industrial one-ply toilet paper. The Aesop soap Tandice is obsessed with instead of pink gas station soap. Marginal costs for the business that do wonders for the patient experience.

On a deeper level, healthcare hospitality means that Lanby members get the distinct feeling that The Lanby gives an immense shit about them. It starts with the basics: reviewing patient charts before the appointment starts, making real eye contact during patient visits, and never asking a patient to repeat the same information twice. And then it’s about going the extra mile: If a member texts them after hours, they’ll probably respond anyway. If they know a member is interested in a particular new fitness movement, they’ll send the member an interesting article about it when they see it. They’ll host classes and events in the office to make The Lanby a fun community.

If all of this sounds a little over the top for a doctor’s office, we should consider whether maybe all of our expectations are in the wrong place for something as important as our health. Tandice and Chloe are convinced that American healthcare has a “tragedy of low expectations” problem. We’re outraged if a restaurant makes us wait for a meal, but not if the doctor makes us wait for our healthcare? We’re outraged if the person at a hotel front desk is unfriendly to us—but we shrug and take a seat when that happens at the doctor’s office? It makes no sense.

Which gets to the bigger point:

The big picture

The American healthcare system is full of problems. But our health also suffers from a human nature problem.

Humans tend to be highly irrational about long-term planning, no matter how important it is. Prioritizing our health seems frivolous when we’re healthy.

This kind of thinking makes The Lanby seem like a luxury service—because $3,000/year is luxurious when spent on something frivolous. But healthcare when you’re healthy is anything but frivolous. It’s critical preventive care—the kind that prolongs (and often saves9) our lives and drastically increases our chance of a happy future (and which ends up saving us money over the long run).

If humans were perfectly rational creatures, we’d all be highly attentive to our health and put the proper effort toward preventive care. But since we’re not, one fix is to hack the human system by sweetening the experience enough that our dumb short-term brains actually like going to the doctor.

If going to the doctor is an easy, lovely experience, we’ll go more often. When there’s an expert who always wants to talk to you about your diet, sleep, and exercise, we’ll live a healthier lifestyle. When it’s incredibly easy to send a text to ask a quick health question, we’ll ask more health questions. When preventive care is a way of life, we’ll have a healthier future.

Tandice and Chloe are excited to run their dream doctor’s office—but they’re most excited about the burgeoning paradigm shift The Lanby could be a part of. A future industry could include lots of iterations on this model, at lots of different price points (some have already sprung up). Their long-term vision is to set a whole new standard for primary care. And once we get used to that new standard, I’m pretty sure the old model will look utterly archaic—and really bad for you.

Founding Memberships

The Lanby is launching in September 2021, starting with 300 “Founding Members”.

They think of Founding Members the way they’d think of a friend who offered to be an advisor—as part of their extended team. Founding Members can meet with the founders, offer early feedback, and help The Lanby be a service for patients, by patients. Ideal Founding Members are people who think a lot about health and would like to have a voice in the future of healthcare.

Brainstorming how they could give back to those critical first members, Tandice and Chloe settled on a lifelong discount. Founding Members will pay only $2,000/year (instead of $3,000/year) for life. When they move into a bigger space, the membership fee will likely go up, but advisory members stay at $2,000/year. When they open multiple locations and offer a higher-priced “all clubs” membership tier, advisory members are in that tier for the same $2,000/year. You get the point. And of course, the team plans to go above and beyond to make sure they have an extra special experience.

Founding Members, and only Founding Members, will also be given the opportunity to invest in the company and sit on an Advisory Member Board. By launching using only membership fees and member investor funds, The Lanby can ensure all incentives remain entirely patient-focused.

If you want to be a Founding Member, sign up here (available to the first 300 people who join). Members can be located anywhere in the U.S., as long as they can make it to Manhattan at least once a year for an in-person visit.

If you have questions about anything I’ve written or anything about the company, email Tandice at [email protected].

I’m also doing a Clubhouse session with Tandice and Chloe this Wednesday at 8pm ET.

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our unannoying-I-promise email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

_______

Wait But Why on a totally different kind of healthcare

The funny thing is this is the significantly simplified version. When you include the government, hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry, etc. it’s even more of a mess.↩

About half of all Americans receive health insurance through their employer. This strange custom is a remnant of the Stabilization Act of 1942, which froze wages and salaries for all the country’s workers. Looking for new ways to attract workers during the wartime labor shortage, employers started offering better health insurance, a loophole that was allowed to increase over time by “a reasonable amount.”↩

This is such a mess for consumers that there’s an entire industry—patient advocacy—devoted to helping people navigate the insurance system and its many codes and methods for getting refunds on unfair charges.↩

There are exceptions for each of these, but this is a reasonable representation of the system as a whole.↩

Tools do exist, but they tend to be such a nightmare to use that patients don’t use them.↩

A recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 45% of 18–29-year-olds no longer have a primary care provider at all.↩

Urgent care clinics are increasingly popular because of their convenience and because they, more than the typical traditional doctor’s office, actually treat patients like customers. They’re conveniently located, take walk-in appointments, and often list their prices. But there’s no continuity—each visit is with a new doctor who knows nothing about you or your health history, and they have a tendency to over-prescribe quick fixes like antibiotics, often when it’s not the correct treatment.↩

Doing an experiment outside the traditional insurance model means it inevitably won’t be accessible to everyone. One thing that does help offset the cost, though, is that by front-loading healthcare spend on primary care, patients can also consider going for a higher deductible, lower monthly payment plan. And there’s the effect on long-term costs (one study found that having a PCP ultimately saves patients 33% on health care costs overall). The membership fee can also be paid using HSA/FSA dollars.↩

According to the CDC, “up to 40% of annual deaths from each of five leading U.S. causes are preventable.”↩