You’re on an airplane when you hear a loud sound and things start violently shaking. A minute later, the captain comes on the speaker and says:

There’s been an explosion in the engine, and the plane is going to crash in 15 minutes. There’s no chance of survival. There is a potential way out—the plane happens to be transferring a shipment of parachutes, and anyone who would like to use one to escape the plane may do so. But I must warn you—the parachutes are experimental and completely untested, with no guarantee to work. We also have no idea what the terrain will be like down below. Please line up in the aisle if you’d like a parachute, and the flight attendants will give you one, show you how to use it and usher you to the emergency exit where you can jump. Those who choose not to take that option, please remain in your seat—this will be over soon, and you will feel no pain.

What would you do?

___________

When Robert Ettinger was a kid in the 1930s, he read a lot of science fiction, and he assumed that with the world advancing the way it was, scientists would surely have a cure for aging at some point during his lifetime. He would live to see a world where sickness was a thing of the past and death was something people chose to do voluntarily, at a time of their choosing.11← New to WBW? Open these.

But thirty years later, aging and involuntary death were still very much a thing, and Ettinger, by then a physics professor, realized that science might not solve these problems in time for him to reap the benefits. So he started thinking about how to hack the system.

If, rather than being buried or cremated after his death, he could instead be frozen in some way—then whenever the scientists did eventually get around to conquering mortality, they’d probably also have the tools and know-how to resuscitate him, and he could have the last laugh after all.

In 1962, he wrote about this concept in a book called The Prospects of Immortality, and the cryonics movement was born.

The first person to give cryonics a try was James Bedford, a psychology professor who died of cancer in 1967 at the age of 73 and is doing his thing in a vat of liquid nitrogen in Arizona as you read this. Others slowly began to follow, and today, there are over 300 people hanging out in vats of liquid nitrogen.

Now let’s pause for a second. A year ago, I knew almost nothing about cryonics, and my impressions of it were something like this sentence:

Cryonics, or cryogenics, is the morbid process of freezing rich, dead people who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to bring them back to life, and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

Then I started learning about it. It’s your fault—cryonics is one of the potential-future-post-topics people email me about most, and it’s something at least five readers have brought up in conversation when I’ve met them in person. And as I began to read about cryonics, I soon learned that a lot of the words in my italicized assumption sentence weren’t correct.

So let’s work our way through the sentence as we go over exactly what cryonics is and how it works. We’ll start with this part:

Cryonics, or cryogenics, is the morbid process of freezing rich, dead people who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to bring them back to life, and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

It turns out that this is like saying, “Wingsuit flying, or meteorology, is the sport of flying through the air using a wingsuit.” Meteorology is the study of what happens in the atmosphere, which includes how wind works, and wingsuit flying is a process that harnesses the wind—and you’d be an odd person if you thought they were the same thing.

Likewise, cryogenics is a branch of physics that studies the production and effects of very low temperatures, while cryonics is the practice of using very low temperatures to try to preserve a human being. Not the same thing.

Next, we have a string of three misleading words to talk about:

Cryonics is the morbid process of freezing rich, dead people who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to bring them back to life, and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

We’ll address these three words by going through how cryonics works, starting at the beginning.

So you decide you want to be a cryonicist. Here are the steps:

Step 1) Pick a company

There are four major companies that provide cryonics services—Alcor in Arizona, Cryonics Institute (CI) in Michigan, American Cryonics Society (ACS) in California, and KrioRus in Russia. KrioRus is the newest option and quickly up-and-coming, but the two big boys are Alcor and CI (ACS doesn’t have their own storage facilities—they store with CI).

From my perusing, it seems like Alcor is the slightly-more-legit and fancier of the two, while CI (which was started by Robert Ettinger, the guy who launched the movement) is more affordable and gives off more of a mom-and-pop vibe. Both are nonprofit, and each has about 150 people in storage. Alcor has a little over 1,000 “members” (i.e. people who will one day be in storage), and CI has around half that number.

Step 2) Become a member

To become a cryonicist, you need to fill out some paperwork, sign some stuff and get it notarized, and pay for three things: an annual membership fee, a transport fee to get your body to the facility after you die, and a treatment/storage/revival fee.

Alcor’s annual membership fee is about $700, and their transport fee is bundled together with the treatment/storage/revival fee—together they cost $200,000. Alcor gives you the option of ditching your body and just freezing your brain (this is called “neuropreservation”), which brings the price down to $80,000.

CI’s annual membership fee is $120 (or a one-time fee of $1,250 for a lifetime membership) and the treatment, etc. costs $35,000 ($28,000 for lifetime members). This is so much cheaper than Alcor for two main reasons:

First, it doesn’t include the transport. If you live near the facility, you can save a lot of money. If not, you’ll need to go through their partner for a transport contract, which costs $95,000 ($88,000 for lifetime members).

Second, Alcor uses more than half of their large fee to fund what they call their Patient Care Trust. Back in the 70s, there were more cryonics companies, and some of them went bankrupt, which meant their frozen people stopped being frozen, which was a not ideal outcome. Alcor’s trust is a backup fund to make sure their “patients” won’t be affected by something like a company financial crisis.

Step 3) Get a life insurance policy in the name of your new cryonics company

Sounds shady, right? But it also makes sense. Both Alcor and CI are small companies on a pretty tight budget and neither can afford to offer a payment plan to be hopefully paid out by your estate or your relatives. On the patient end, unless you’re rich, cryonics fees are huge, and a life insurance policy guaranteed to pay your full cryonics fee forces you to save for this fee throughout your life. For young people, even sizable life insurance policies are pretty cheap—with CI, you could be totally covered for as little as $300/year ($120 annual membership, $180 life insurance policy to cover the main fee). Even for Alcor’s more expensive package, costs shouldn’t exceed $100/month.

Those fees aren’t nothing, but the whole life insurance thing, at least when it comes to younger people, pretty effectively ejects “rich” from our black and red sentence. If it costs the same as cable or a cigarette habit, you don’t need to be rich to pay for it.

Step 4) Put on your bracelet and go on living your life

Cryonics members are given a bracelet and a necklace, etched with instructions and contact info, and encouraged to wear one at all times, so if you suddenly die, whoever finds you will know to notify the company.

Step 5) Die

Okay here’s where things get tricky. We think of the divide between life and death as a distinct boundary, and we believe that at any given point, a person is either definitively alive or definitively dead. But let’s examine that assumption for a second:

Let’s first talk about what it means when a person is “doomed” from a health standpoint. We can all agree that what constitutes someone being doomed depends on where, and when, they are. A three-year-old with advanced pneumonia in 1740 would probably have been doomed, while the same child with the same condition today might be fully treatable. The same story could be said of the fate of someone who falls badly ill in a remote village in Malawi compared with their fate if they were in London instead. “Doomed” depends on a number of factors.

That the same thing can be said of “dead” is at first pretty unintuitive. But Alcor’s CEO Max More puts it this way: “Fifty years ago if you were walking along the street and someone keeled over in front of you and stopped breathing you would have checked them out and said they were dead and disposed of them. Today we don’t do that, instead we do CPR and all kinds of things. People we thought were dead 50 years ago we now know were not.”2

Today, dead means the heart has been stopped for 4-6 minutes, because that’s how long the brain can go without oxygen before brain death occurs. But Alcor, in its site’s Science FAQ, explains that “the brain ‘dies’ after several minutes without oxygen not because it is immediately destroyed, but because of a cascade of processes that commit it to destruction in the hours that follow restoration of warm blood circulation. Restoring circulation with cool blood instead of warm blood, reopening blocked vessels with high pressure, avoiding excessive oxygenation, and blocking cell death with drugs can prevent this destruction.”3 The site goes on to explain that “with new experimental treatments, more than 10 minutes of warm cardiac arrest can now be survived without brain injury. Future technologies for molecular repair may extend the frontiers of resuscitation beyond 60 minutes or more, making today’s beliefs about when death occurs obsolete.”

In other words, what we think of as “dead” actually means “doomed, under the current circumstances.” Someone fifty years ago who suffered from cardiac arrest wasn’t dead, they were doomed to die because the medical technology at the time couldn’t save them. Today, that person wouldn’t be considered dead yet because they wouldn’t be doomed yet. Instead, someone today “dies” 4-6 minutes after cardiac arrest, because that happens to be how long someone can currently go before modern technology can no longer help them.

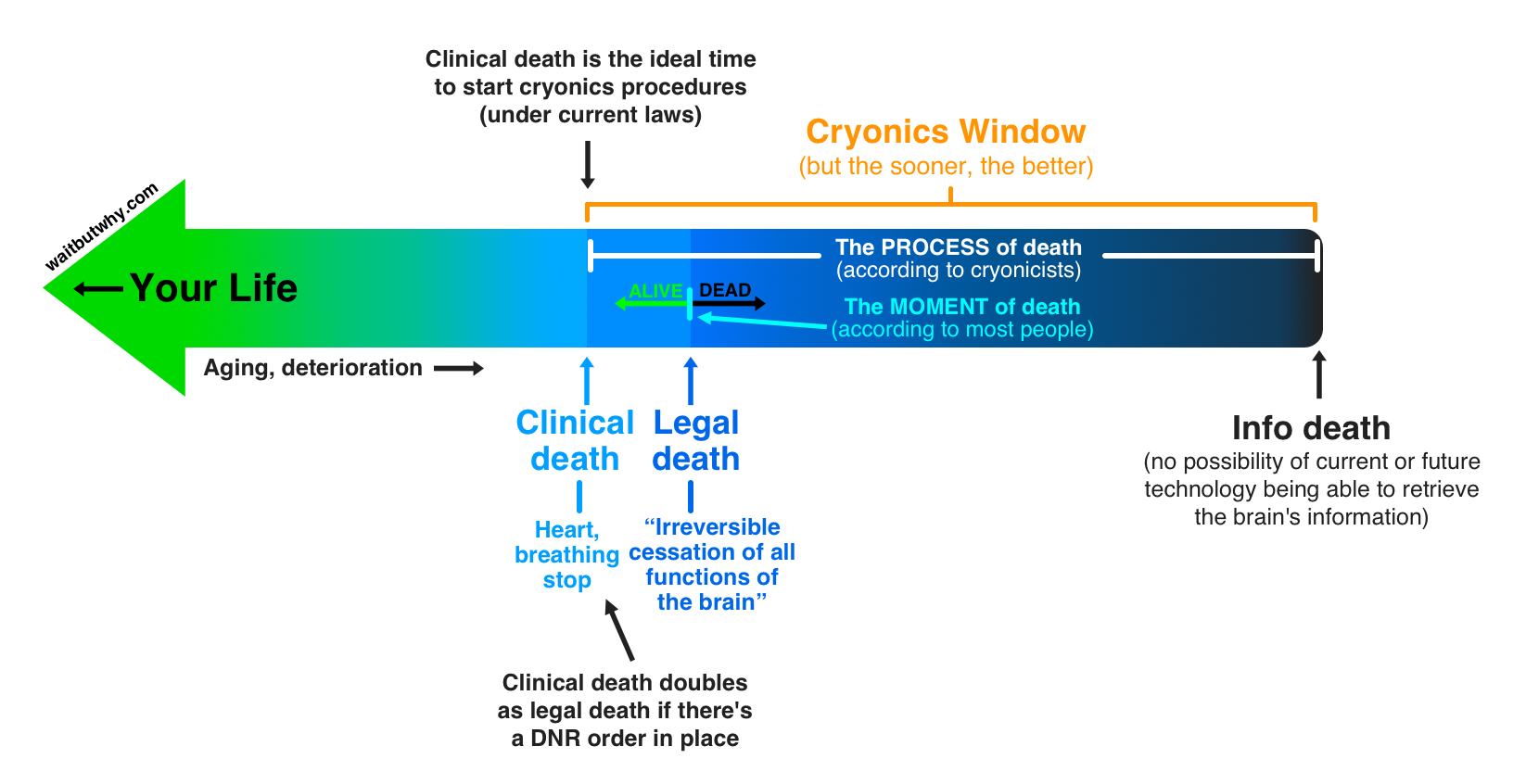

Cryonicists view death not as a singular event, but as a process—one that starts when the heart stops beating and ends later at a point called “the information-theoretic criterion for death”—let’s call it “info death”—when the brain has become so damaged that no amount of present or future technology could restore it to its original state or have any way to retrieve its information.

Here’s an interesting way to think about it: Imagine a patient arriving in an ambulance to Hospital A, a typical modern hospital. The patient’s heart stopped 15 minutes before the EMTs arrived and he is immediately pronounced dead at the hospital. What if, though, the doctors at Hospital A learned that Hospital B across the street had developed a radical new technology that could revive a patient anytime within 60 minutes after cardiac arrest with no long-term damage? What would the people at Hospital A do?

Of course, they would rush the patient across the street to Hospital B to save him. If Hospital B did save the patient, then by definition the patient wouldn’t actually have been dead in Hospital A, just pronounced dead because Hospital A viewed him as entirely and without exception doomed.

What cryonicists suggest is that in many cases where today a patient is pronounced dead, they’re not dead but rather doomed, and that there is a Hospital B that can save the day—but instead of being in a different place, it’s in a different time. It’s in the future.

That’s why cryonicists adamantly assert that cryonics does not deal with dead people—it deals with living people who simply need to be transferred to a future hospital to be saved. They believe that in many cases, today’s corpse is tomorrow’s patient (which is why they call their frozen clients “patients” instead of “corpses” or “remains”), and they view their work as essentially “extended emergency medicine.”4

But it’s emergency medicine with an important caveat. Today’s technology has no way to revive a cryonically-suspended patient, so it isn’t considered a medical procedure by the law but rather a weird kind of coffin—i.e. if you cryopreserve someone who hasn’t yet been pronounced dead, it’s seen by the law as homicide. Even if the patient is terminally ill beyond any hope and adamantly doesn’t want to deteriorate further before being cryopreserved, it’s not an option—at least not under current laws (laws that some are trying to change). This puts cryonicists in a tough bind—and it’s exactly where that differing definition of death comes in handy.

The law does not see death as a process. For a long time, legal death in the US was considered to occur when a person’s heartbeat and breathing stopped. As modern medical procedures like CPR and defibrillators started to allow those patients to be resuscitated, the law had to change the definition of legal death to include “irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain.”5 The old “heartbeat and breathing” definition of legal death is now called “clinical death,” a middle ground point where there’s an obligation to attempt resuscitation in most cases but where a patient can also have a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order in place (common with terminally ill patients).2 In DNR cases, a doctor or nurse will pronounce a clinically dead patient to be legally dead—even though a resuscitation effort could still revive them.

This is a critical fact for cryonics. Cryonics technicians have to wait until legal death to begin their work on a patient, but with the help of a patient’s DNR order, they can start the process right after the heart stops, well before any brain damage sets in.

So this is the window for cryonics:

Which brings us back to our list, where we can now clarify what we really mean with Step 5:

Step 5) Legally Die

You legally dying is a key step along the way here, so don’t mess it up. You can do it the good way, the bad way, or the really bad way.

The good way: Something predictable where you’re in a cliché deathbed situation, like cancer. This allows you to get yourself on a plane to either Scottsdale (Alcor) or Michigan (CI) and into one of the specifically designated hospice care facilities that the cryonics company regularly works with. This is important because cryonics is highly controversial within the mainstream medical community and often not well-regarded or well-understood. As a result, some hospitals and hospice care facilities are “cryonics friendly” and others are not (those that aren’t have been known to make it difficult for cryonics staff to do what they need to do or deny them the same privileges organ transplant specialists get in a hospital). Once you’re in hospice care, the cryonics company can put staff on standby around the clock, so that the second you legally die, they can be there to start the treatment.

The bad way: Something sudden and unexpected, like a heart attack, where at best, someone is there and can contact the cryonics company as you’re rushed to the hospital so they can meet you there, or worse, where you’re dead for a few hours or even longer before anyone finds you. In these circumstances, the cryonics company will do the best they can. Your brain will be in worse shape than ideal when you go into cryopreservation, but again, who knows what future technology will be able to accomplish, and as long as you’re still somewhere in the “cryonics window” and still in the process of dying, not yet having reached info death, there remains hope.

The really bad way: A violent accident or something where your brain ends up badly damaged. In the worst of these cases, there’s not much cryonics can do to help—like the Alcor member who died in the September 11th attacks.6 Another bad ending would be dying in a foul-play situation that would lead the police to want to do an autopsy (Alcor suggests its members file a no-autopsy-for-religious-reasons form with the government). A woman who has signed up for cryonics did a Reddit AMA, and when one of the questions was about how signing up had changed her life, she answered, “The biggest change I’ve noticed is that I’m more careful. I drive slower and more cautiously/attentively, I pay more attention to what’s going on around me.” Because she doesn’t want to die the really bad way.

Step 6) Cool off ASAP and get transferred to the cryonics facility

After you’re declared legally dead, the cryonics team will, ideally, immediately get going. The first thing they do is two-fold—they put you in an ice water bath to bring down your temperature and slow your metabolism (so any damage taking place as a result of cardiac arrest takes longer to happen), and they start getting your heart and lungs working again so that the body remains in stable condition. They do this by administering CPS (like CPR but with an S for support instead of an R for resuscitation, because they’re not trying to resuscitate you) using a mechanical heart-lung resuscitator called a thumper:7

Then they inject you with a number of different medicines to make sure you don’t get blood clots or start rotting.

Once that’s under control, they can do a more involved procedure that surgically accesses the major blood vessels in your thigh and hooks them up to this guy:8

That’s a heart-lung machine that takes care of circulation and oxygenation so they can stop the much cruder CPS. In addition to circulating your blood, the machine draws heat out of your body, cooling it to just above the freezing temperature of water, and replaces some of your blood with an organ preservation solution that supports life at super low temperatures (this is similar to how transplant surgeons keep organs alive when they have to transport them long distances).

If you have to be flown to the cryonics facility, they pack you in ice and put you on board what they hope is not your last ever flight.

Step 7) Get vitrified

Most people who know what cryonics is think it means getting frozen. It doesn’t. It means getting vitrified.

Glass is weird. It’s not a typical solid because as it cools from its liquid phase, it never crystallizes into an orderly structure. But, as I learned when a bunch of commenters yelled at me after I published this post, it’s not actually a liquid either, since it doesn’t flow. So, it’s neither a typical solid nor a liquid—it’s an “amorphous solid,” sometimes compared to a giant molecule. For our purposes, the key is that like a liquid, glass doesn’t crystallize—rather, as it cools the molecules just move slower and slower until they stop.

If you froze a human, all the liquid water in their body would eventually hit its freezing point and crystallize into a solid. That wouldn’t be good—first, water ice takes up about 9% more volume than water liquid, so it would expand and badly damage tissue, and second, the sharp ice crystals would slice through cell membranes and other tissue around it.

So to avoid that catastrophic liquid-to-solid state change, cryonics technicians do something cool—they perform surgery through the chest and hook the major arteries up to tubes which pump all the blood out of the body, replacing it with a “cryoprotectant solution,” otherwise known as medical grade anti-freeze. This does two important things: it replaces 60% of the water in the body’s cells, and it lowers the freezing point of what liquid is left. The result, when done perfectly, is that no freezing happens in the body. Instead, as they chill your body down and down over the next three hours, it hits -124ºC, a key point called the “glass transition temperature” when the body’s liquid stays amorphous but rises so high in viscosity that no molecule can budge. You’re officially an amorphous solid, like glass—i.e. you’re vitrified.

With no molecule movement, all chemical activity in your body comes to a halt. Biological time is stopped. You’re on pause.

Since I’m sure you’re feeling skeptical, it’s helpful to note that vitrifying biological parts is nothing new. We’ve been successfully vitrifying and then rewarming human embryos, sperm, skin, bone, and other body parts for a while now. More recently, scientists vitrified a rabbit kidney:9

Then they rewarmed it and put it back in the rabbit. And it still worked.

And just in February of 2016, there was a cryonics breakthrough when for the first time, scientists vitrified a rabbit’s brain and showed that once rewarmed, it was in near-perfect condition, “with the cell membranes, synapses, and intracellular structures intact … [It was] the first time a cryopreservation was provably able to protect everything associated with learning and memory.”10

Once you’re vitrified, you need to keep being chilled, little by little, until after about two weeks, you’re down to -196ºC. Why? Because that’s the point at which nitrogen becomes a liquid, and you’re about to take a long-term liquid nitrogen bath.

Step 8) Go into storage

Or as Alcor euphemistically calls it, “long-term care.” The new vitrified you now goes into what is essentially a large upright thermos that’s about 10 feet tall and 3.5 feet wide.11

You meet your new neighbors—three other vitrified people, each in their respective quadrant of the thermos, along with five people traveling super lean, with no body, whose heads are stacked in the middle column.12

Or, if you’re in a heads-only thermos, you’ll be one of 45 brains sharing the space (the brain is what’s being stored, but they keep the brains in their heads because it’s riskier to remove a brain than to just keep it in there and use the head as a carrying case).

Oh, and you’re upside-down. This is because liquid nitrogen boils off gradually from the top of the container. Normally, it’s no problem—the staff tops it off about once a week. But if, in some worst-case scenario, a container was forced to be left for a long time, the head would be the last thing to be affected—upside-down patients means it would take six months before the nitrogen boiled off so far that the head would be exposed.

And when it comes to blackouts, cryonics patients are totally safe—there’s no electricity involved in their storage.

And this is where you’ll hang out. Maybe for 10 years. Maybe for 150 years. Maybe for 1,200 years. But the time doesn’t matter to you. You’re on pause.

Now’s a good time for us to take a step back and look at the big picture. If Point A is “I’ve decided I want to sign up for cryonics,” and Point B is “Oh cool it’s the year 2482 and here I am doing stuff,” there are four major Ifs that need to all go the right way to take you from A to B:

1) If I legally die in a not really bad way and everything goes as planned with getting me into the thermos

and

2) If future humanity ever reaches a point where it has the technology to revive me to full health

and

3) If the cryonics company can manage to store me safely and uninterrupted until that point

and

4) If when that point comes, the outside world actually does take action to revive me

—then I’ll be there in 2482 doing stuff.

The eight steps you’ve taken so far that start with choosing a cryonics company and end with you in the thermos only accomplish the first If, with all the other Ifs still standing in between you and the next step in your cryonics journey—revival.

To understand how we can reach that step, we need to understand the deal with all four Ifs.

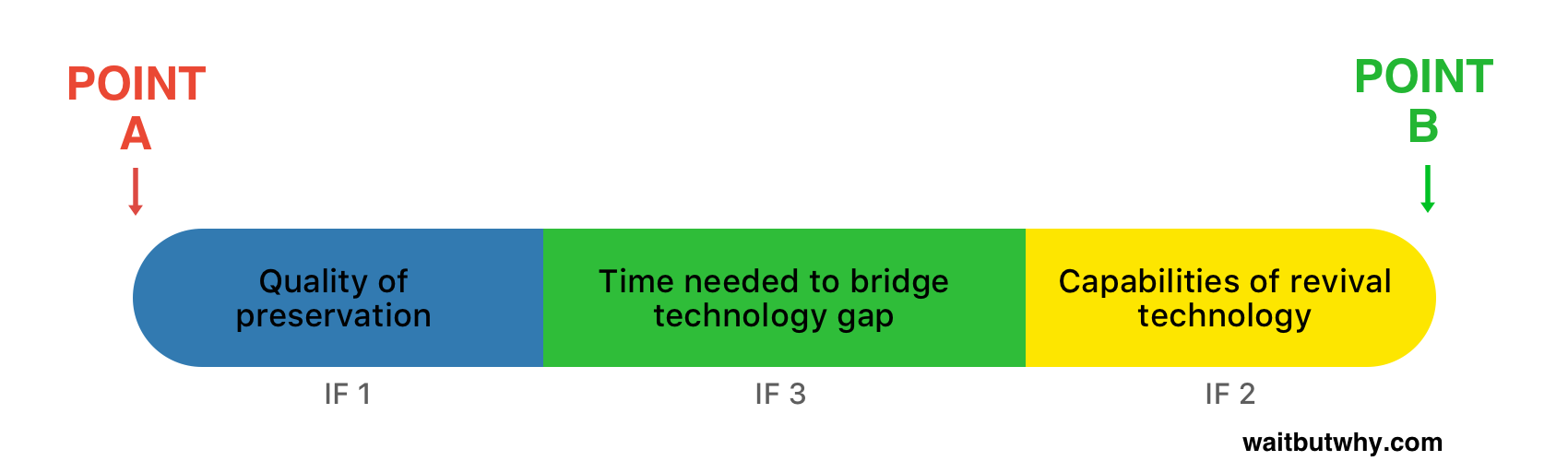

We’ll start by talking about Ifs 1-3, which need to be discussed together, because they’re interdependent and they work together. To illustrate why, let’s lay them out in the same visual:

The three segments of this line relate to Ifs 1, 2, and 3. But the visual is a little misleading at first, because even though all three segments lie on the same line, they’re all representing different concepts:

- The blue segment (If 1) represents the quality of your initial preservation.

- The yellow segment (If 2) represents the capabilities of medical technology as time moves forward.

- The green segment (If 3) represents the amount of time still needed to bridge the gap between the blue and yellow segments before they can finally connect to each other.

The idea is that the better you were preserved, the farther out to the right the blue segment extends, and as technology gets better and better, the yellow segment extends itself farther and farther left toward the blue segment. The green segment gets smaller and smaller as this happens, until eventually the green segment is no more and the blue and yellow segments connect—i.e. medical technology has reached the point where it can revive you.

A lot of the key details about cryonics are centered here, so let’s talk about each of these segments in more depth:

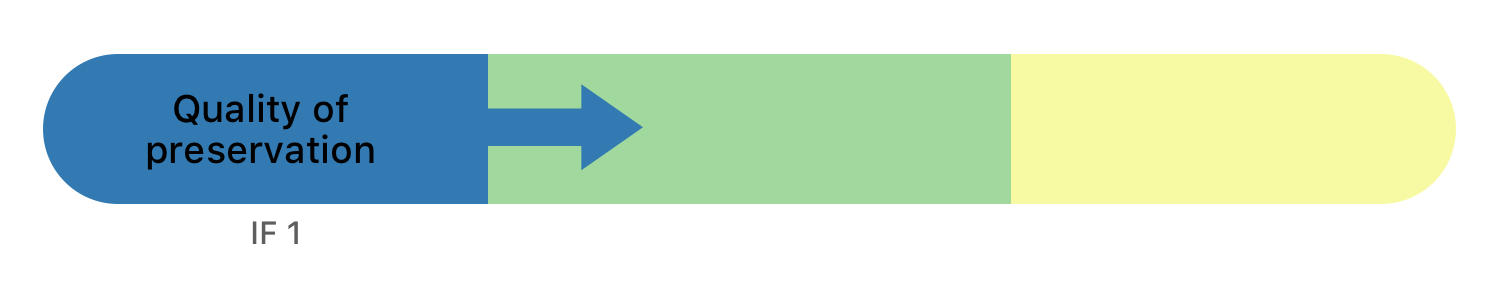

The blue segment—the quality of your preservation (which relates to If 1)

The length of the blue segment corresponds to the quality of preservation. Or, put most simply, the fewer roadblocks there are between your vitrified state in the thermos and a fully restored and healthy you, the longer the blue segment is—because if everything that happens leading up to you being put in the thermos goes as well as possible, it goes a longer way towards getting you to Point B and means the yellow segment has to do less work on its end to be able to revive you.

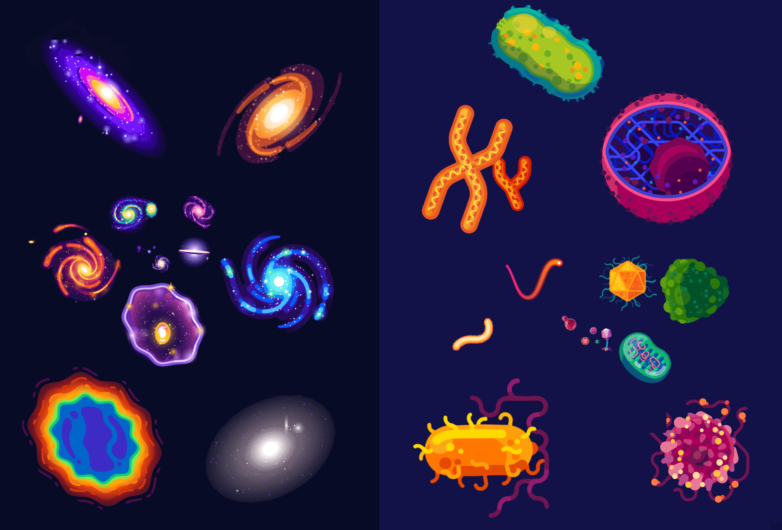

The major factor that determines the length of the blue segment is how closely the atomic structure of your vitrified brain resembles the original atomic structure of your brain when it was living and healthy.

Let’s note that I said “brain,” not “body,” because what we mostly care about here is the brain. Cryonicists, like many of us, believe that who you are comes down to your brain. If, in the future, your identical current brain lived on top of a synthetic body and your exact memories and personality were fully intact, cryonicists would be satisfied that you “survived.” That’s why some don’t even bother vitrifying their body.

The second thing to note is that scientists believe that short-term memory is contained in brain activity—in the electricity going through your brain—while your long-term memory, your personality, your knowledge, and everything else that makes you “you” is contained in the brain’s structure—i.e. the particular arrangement of atoms that make up your brain.13

Any electrical activity in your brain before legal death will be lost during vitrification, so you’d be revived without the short-term memory of the end of your pre-vitrified life. But what vitrification can preserve is the structure of your brain, which conveniently, is all we care about.

This concept gives us a clearer understanding of the way cryonicists view death. To cryonicists, perfect health means the exact arrangement of atoms in your healthy brain being intact, and the process of dying means the deterioration of that arrangement due to phenomena like aging, injury, disease, and, eventually, effects caused by heart stoppage. Death, to them, means the point at which the original structure of your brain has become so disorganized that even the fanciest future science lab would have no way of figuring out what the original arrangement looked like—that’s the definition of info death.

The concept of info death makes sense when we compare the brain to a computer’s hard drive. Eliezer Yudkowsky explains how difficult it actually is to bring a computer hard drive to info death:14

If you want to securely erase a hard drive, it’s not as easy as writing it over with zeroes. Sure, an “erased” hard drive like this won’t boot up your computer if you just plug it in again. But if the drive falls into the hands of a specialist with a scanning tunneling microscope, they can tell the difference between “this was a 0, overwritten by a 0” and “this was a 1, overwritten by a 0”.

There are programs advertised to “securely erase” hard drives using many overwrites of 0s, 1s, and random data. But if you want to keep the secret on your hard drive secure against all possible future technologies that might ever be developed, then cover it with thermite and set it on fire. It’s the only way to be sure.

He applies the same logic to the human brain to suggest that cryonics patients should one day be revivable:

Pumping someone full of cryoprotectant and gradually lowering their temperature until they can be stored in liquid nitrogen is not a secure way to erase a person.

In other words, it’s reasonable to assume that the fanciest future neuroscientists will become so good at reading a damaged vitrified brain for clues as to its original structure that a typical combo of aging, disease, heart stoppage, and vitrification likely won’t be able to “stump” them. And to cryonicists, if future scientists can examine your vitrified brain and figure out what it’s supposed to look like, you’re not dead—by definition.

The length of the blue segment—preservation quality—is affected by three things:

1) How much damage happened before you legally died. How old were you when you died? How much had your brain deteriorated by that point? Did you suffer from a dementia-causing disease like Alzheimer’s and how much permanent damage did that disease do?3 Did the thing that killed you damage your brain (like brain cancer, or a head injury) or was your brain unharmed?

2) How much damage happened between when you legally died and when the cryonics team started working on you. In the ideal situation, your heart stops and before any changes happen in your brain, you’re stabilized and put on ice. Often, this isn’t how things go, and every unattended minute that passes after legal death has a big impact on the brain and shortens the length of the blue segment. But cryonicists believe that true info death doesn’t happen for many hours, or even days, after legal death occurs, and that there’s often hope in cryopreserving even people who lay “dead” for a while before being found.

3) How much damage happened during the vitrifying process. Vitrification itself—at least the way it is currently done—causes its own damage to the brain. Cryonics research focuses mostly on mitigating this factor, and it’s dramatically improved since the earliest days in the 1970s—the series of images at the bottom of this page shows the progress that has been made.

The yellow segment—the state of medical technological advancement as time moves forward (which relates to If 2)

As medical technology becomes more and more advanced, the yellow segment grows—but while the blue segment extends to the right as it grows, the yellow segment extends to the left. The key point happens when technology eventually gets so good that the yellow segment meets the blue segment and you become officially revivable.

Some questions:

Will If 2 happen? Will technology ever reach the point when it can revive you?

Assuming If 1 gets a check mark, cryonicists believe If 2 is likely to one day get a check mark too. Because there are only two ways to totally fail If 2:

1) For some reason, humans permanently stop working on medical technology advancements before you hit the If 2 key point.

2) Humans go extinct before hitting the If 2 key point.

Barring those two situations, If 2 should eventually cooperate. The theory is that with enough future technology, you’ll one day be revivable.

When will If 2 happen? How long until I’m revived?

This part depends on how substantial the technological challenge of cryonic revival turns out to be and how quickly technology ends up moving forward—but it also depends upon how well If 1 went. As we just discussed, the better If 1 goes, the sooner If 2 happens.

How will If 2 happen? What kind of future technology might be able to revive vitrified people?

Well, it depends on what we mean by revival. Cryonicists seem to have a Plan A and a Plan B.

Plan A: Restore the vitrified patient as a healthy human

Under Plan A, revival consists of restoring the structure of the vitrified brain to its original state—i.e. putting all the atoms where they belong. To do that, you need two things:

1) The info about where the atoms are supposed to go

2) A way to put the atoms where they’re supposed to go

The first thing is taken care of if today’s vitrifying procedures do their job, assuming future neuroscientists become really good at deciphering a brain’s original state from the information they can gather by examining the vitrified brain.

The second thing requires molecular nanotechnology. For a quick nanotech overview, I’ll steal part of a blue box from the AI post:

Nanotechnology Blue Box

Nanotechnology is our word for technology that deals with the manipulation of matter that’s between 1 and 100 nanometers in size. A nanometer is a billionth of a meter, or a millionth of a millimeter, and this 1-100 range encompasses viruses (100 nm across), DNA (10 nm wide), and things as small as large molecules like hemoglobin (5 nm) and medium molecules like glucose (1 nm). If/when we conquer nanotechnology, the next step will be the ability to manipulate individual atoms, which are only one order of magnitude smaller (~.1 nm).4

To understand the challenge of humans trying to manipulate matter in that range, let’s take the same thing on a larger scale. The International Space Station is 268 mi (431 km) above the Earth. If humans were giants so large their heads reached up to the ISS, they’d be about 250,000 times bigger than they are now. If you make the 1nm – 100nm nanotech range 250,000 times bigger, you get .25mm – 2.5cm. So nanotechnology is the equivalent of a human giant as tall as the ISS figuring out how to carefully build intricate objects using materials between the size of a grain of sand and an eyeball. To reach the next level—manipulating individual atoms—the giant would have to carefully position objects that are 1/40th of a millimeter—so small normal-size humans would need a microscope to see them.5

Nanotech was first discussed by Richard Feynman in a 1959 talk, when he explained: “The principles of physics, as far as I can see, do not speak against the possibility of maneuvering things atom by atom. It would be, in principle, possible … for a physicist to synthesize any chemical substance that the chemist writes down…. How? Put the atoms down where the chemist says, and so you make the substance.” It’s as simple as that. If you can figure out how to move individual molecules or atoms around, you can make literally anything. Nanotechnology so advanced that it allows us to engineer at an atomic level is called molecular nanotechnology (MNT).

Humans haven’t yet conquered MNT, and scientists debate how long it’ll take humanity to get there. But when we do, we might look back on today’s technology as terribly primitive, like the picture scientist Ralph Merkle paints: “Today’s manufacturing methods are very crude at the molecular level. Casting, grinding, milling and even lithography move atoms in great thundering statistical herds. It’s like trying to make things out of LEGO blocks with boxing gloves on your hands. Yes, you can push the LEGO blocks into great heaps and pile them up, but you can’t really snap them together the way you’d like.”

MNT will be a game-changer in an unimaginable number of arenas, one of which is in medicine. A brain synapse is just a particular configuration of atoms, so if we have the tools to move atoms around and put them where we want, then we can perfectly “repair” a damaged synapse. Cryonicists believe MNT is the key to the future revival and restoration of cryonics patients.

The first thought some people have when they think about revival is that the person would be revived as the old and dying person they were before being vitrified. But that’s not the plan. When we get to the point when we have technology so incredible that we can move atoms around well enough to revive someone, we should also have the technology to repair and rejuvenate them. For someone who was dying of cancer before going into the thermos, not only will their successful revival mean that cancer has likely been conquered long ago, but probably aging too.

Along the same lines, by that point we should also be able to either rejuvenate the patient’s vitrified body or simply make a new, perfectly-working body. Alcor’s Medical Response Director, Aaron Drake, explains: “We know we can regenerate a small organ, and grow a new heart. We know we can 3-dimensionally print cells and hearts. So at some point we would need to regenerate her entire body, or at least her organs, and put it all together. Then we’d need to transplant that brain into a new body.”15

Plan B: Upload the person’s brain info into a virtual world

Plan B shares Plan A’s first requirement—the info about where the atoms are supposed to go—but not its need for physical assembly. Instead, Plan B relies on a hypothetical future technology called “whole brain emulation,” where an entire brain structure can be uploaded to a computer with such perfect accuracy that everything about the person is intact and alive in a virtual world.

Sounds super fun, right?

This is an option if physical revival is too difficult, or if it’s so far in the future that the physical world has actually gone out of style entirely. If humans can somehow pull off whole brain emulation, you could be revived to wake up in a magical virtual world, fully conscious and no longer confined to the limits and vulnerabilities of biology and the physical world. Please.

While both Plan A and B require immense technological hurdles, cryonicists stress that both options are theoretically possible.

The green segment—the amount of time you need to stay safely in storage before technology is able to revive you (which relates to If 3)

The green segment’s job is simple: hold everything together until the yellow segment connects to the blue segment.

So what could mess up If 3? What could sabotage a vitrified person’s ability to remain bathed in liquid nitrogen as long as necessary?

A lot of things. Like:

The cryonics company screws up. A human-error-caused catastrophe—e.g. a rupture in a thermos tank lets in heat, and all the liquid nitrogen evaporates before the staff realizes what happened.

The cryonics company goes bankrupt and doesn’t have the means, the will, or the organization to create a plan that will save the patients. I mentioned that this happened a few times with some of the earlier companies. The major companies today claim to have secure backup plans in place in case of the worst case scenario, and this security blanket is the main purpose of Alcor’s sizable trust.

A natural disaster. An earthquake, tornado, or something else smashes the building holding the thermoses to oblivion. Neither major US cryonics company is in a location highly prone to natural disasters—Alcor actually located itself in Scottsdale, AZ because it is the place in the US least at risk of natural disasters. Even if a natural disaster were to strike, the patients might be fine—the thermoses are strong, they’re power-outage-proof with no electricity involved, and even if a thermos is ruptured, there’s the upside-down thing where patients’ heads will be the last body part affected.

A terrorist attack on a cryonics facility. There are a lot of people in the world—especially in the world of religion—who hate the concept of cryonics.

War. All bets are off in war.

The law prevents the cryonics company from doing its job. This one almost happened recently. In 2004, Arizona legislators tried to pass a bill that would have put Alcor under the regulation of the State Funeral Board. This, if passed, would have likely ended up shutting Alcor down. It turned into a nasty debate, centered largely around religious issues, with the religious voice disapproving of Alcor’s line of work—but ultimately, Alcor prevailed. That said, in order to do business legally, Alcor has to accept bodies in the guise of “anatomical donations for research purposes,” a practice protected by the constitutional right to donate one’s body for research into cryopreservation. The law-related variable seems pretty stable currently, but if someone has a long green segment and requires 800 years of storage before their revival becomes possible, who the hell knows what will happen—what is currently Scottsdale, AZ might not even be part of the US by that point.

The cryonics company comes under ownership with different values and they decide to give up on the patients. Or, more maliciously, a cryonics-hater makes a too-good-to-refuse offer to the owners of a cryonics company with the intention of shutting it down. All major cryonics companies claim that they’re run and always will be run by passionate cryonicists and this is not a possibility—but again, who knows.

The longer the green segment is and the longer it needs to hold out, the higher the chance of failing If 3. If patients can be revived 40 years from now, there’s a lot less that can go wrong than if revival doesn’t become possible for 2,500 years.

But the companies are doing their best to plan for the long run. On the question of how long until revival becomes possible, Alcor says, “Some think it will take centuries before patients can be revived, while others think the accelerating pace of technological change might so rapidly transform our world that decades would suffice. Alcor is planning for however long it might take.”16

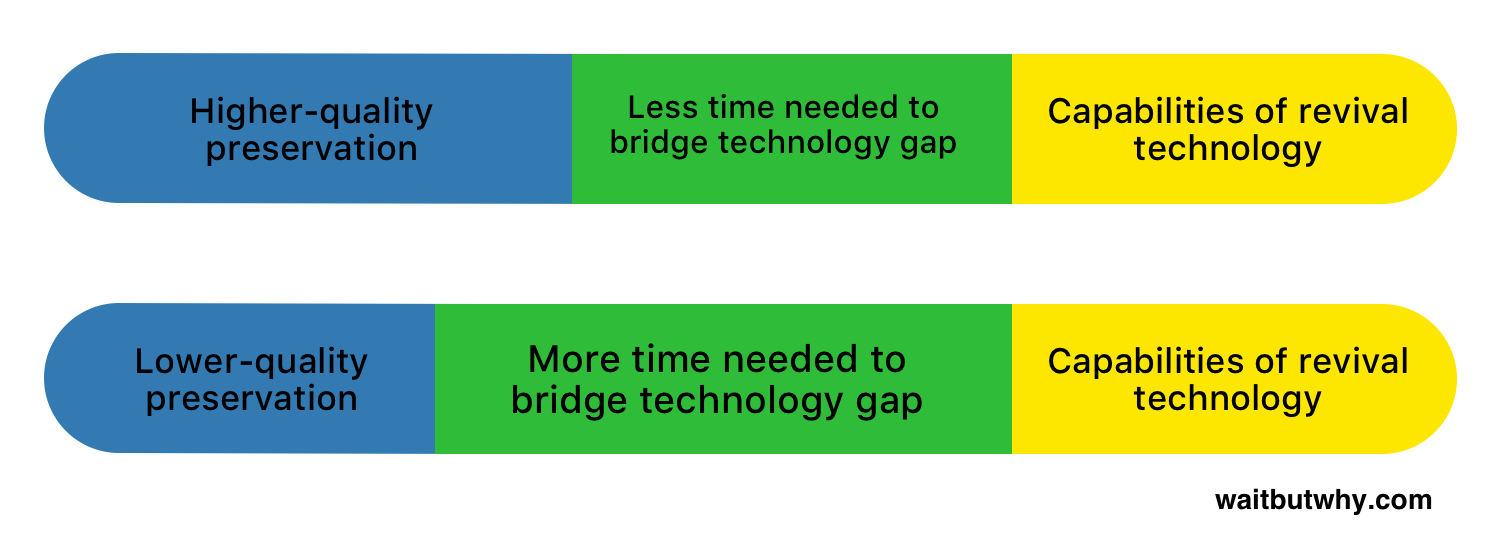

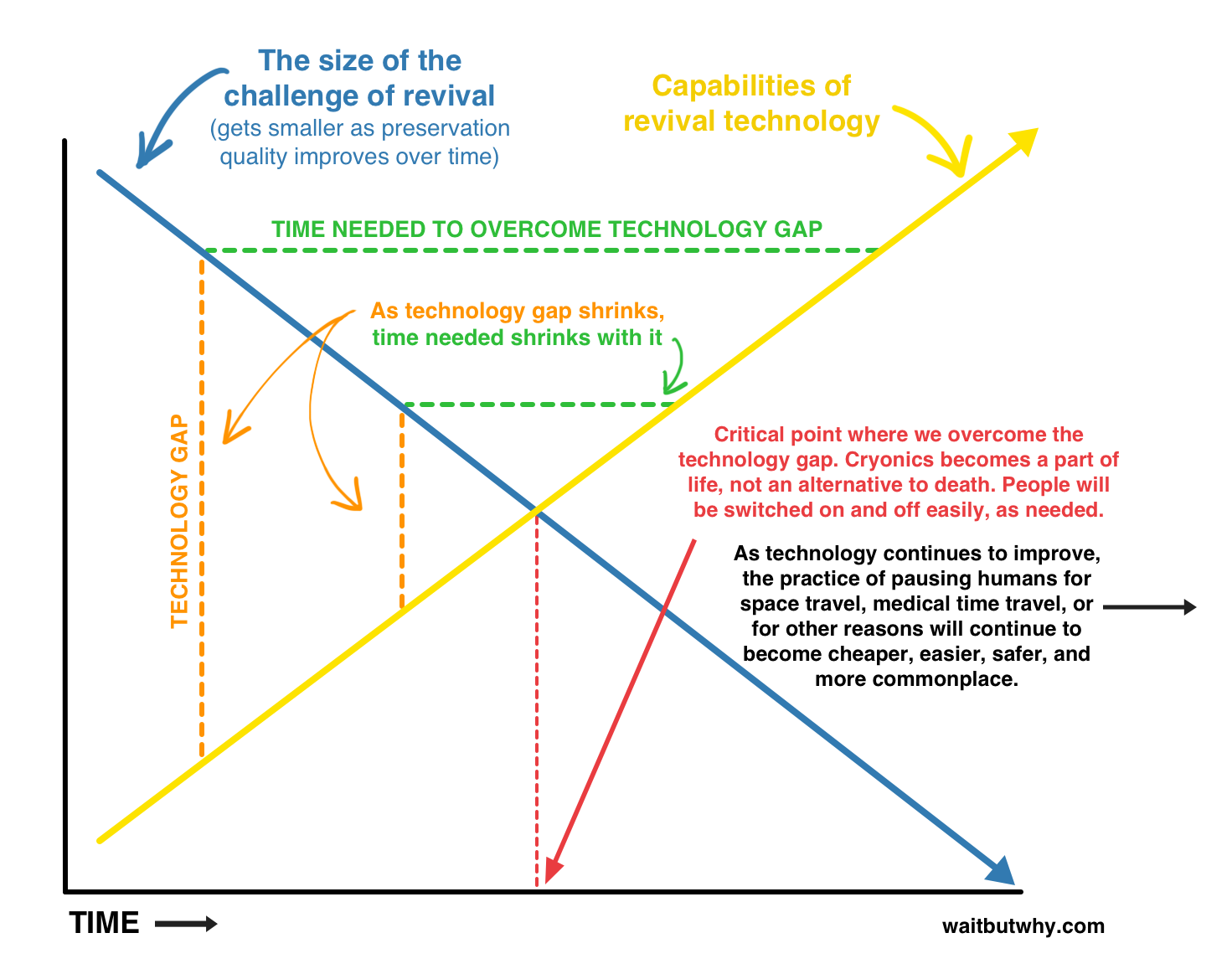

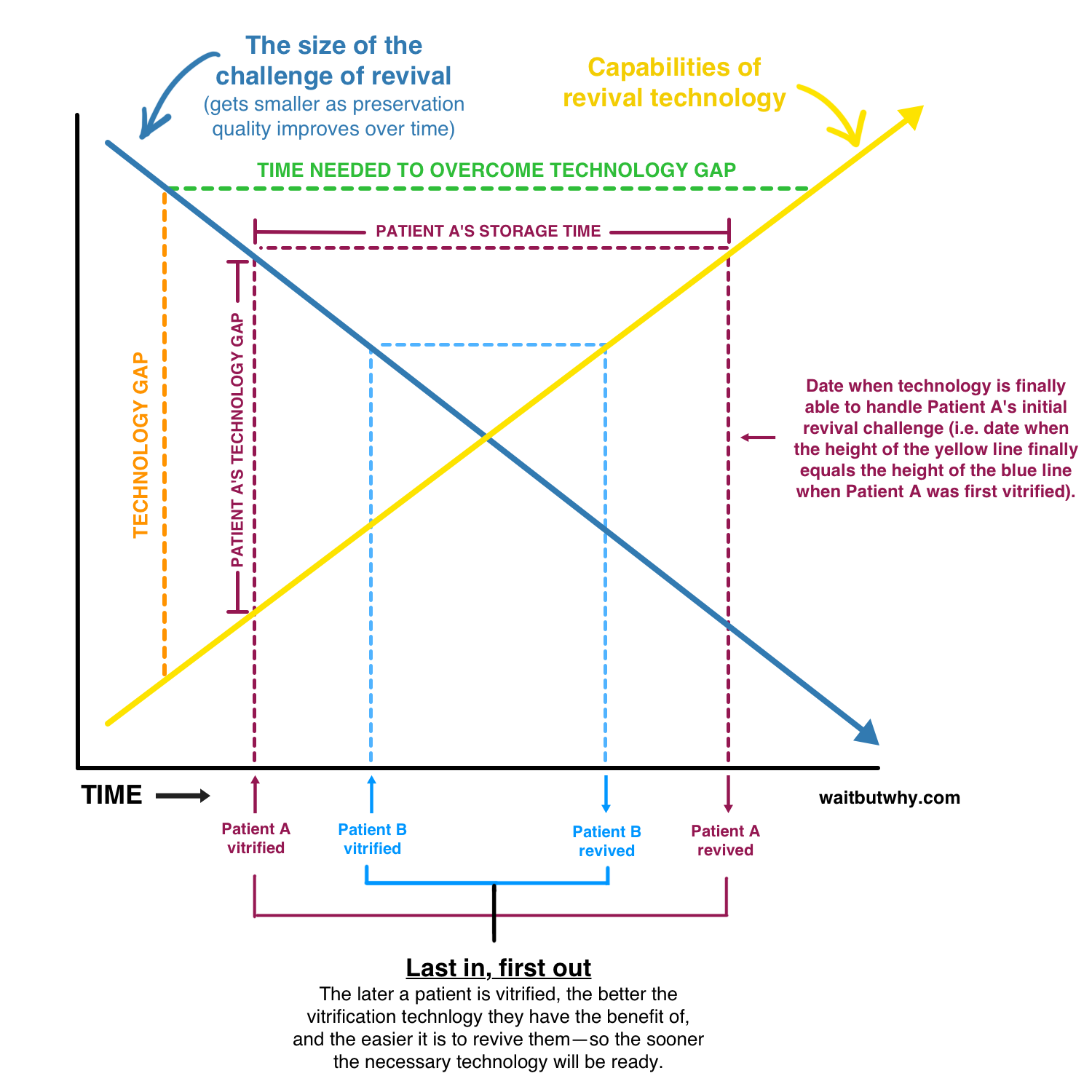

As time moves forward and both vitrification and revival technology improve, both the blue and yellow segments will tend to move inward, invading the green segment from both sides. The big picture might be best illustrated like this:

This is how the blue, green and yellow segments work in flow with each other. Cryonics companies often say cryonics will be a “last in, first out” thing, and this graph shows exactly why—

The more time that passes before you need to be vitrified, the fancier the vitrification technology you’ll be treated with and the further along revival technology will be—and this smaller technology gap will mean a sooner revival date. And with less time to have to rely on a cryonics company to care for you, the less risk you’ll be taking.

It’s important to understand that the blue line on the graph applies to the average cryonics patient—someone who suffers from Alzheimers late in life will go into vitrification in worse shape than a typical person of their time, so their particular challenge will be greater than the blue line height that corresponds with the year of their death.

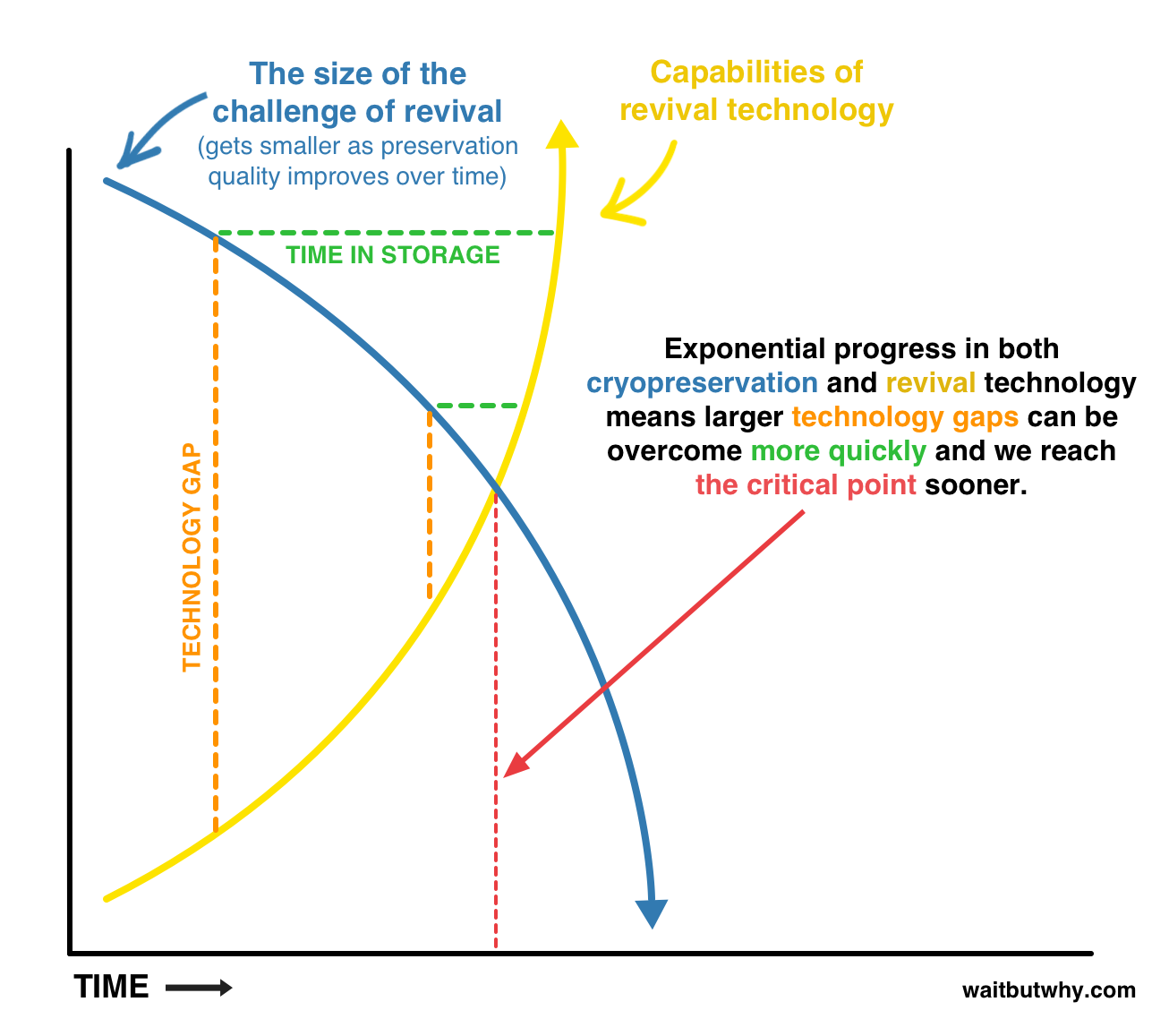

Of course, the simple, straight lines on the graph are portraying the general concept. The actual lines won’t be straight or predictable. One promising way this might be the case is that the accelerating rate of technological advancement6 might mean that the blue and yellow lines could improve at a faster rate over time and look like this:

So that’s how the first three Ifs work. And that’s all great—but none of it matters if If 4 doesn’t pan out. Without If 4—i.e. “Will people actually revive me when the time comes?”—you’re still just a helpless, vitrified body, and if the external world doesn’t keep their side of the bargain once you become revivable, you’re out of luck—and you’ll never know it happened.

You’ll be a little like a farm animal. You might have rights in theory, but with no ability to defend your own rights, you’ll rely on other people to fight for those rights on your behalf.

As I’ve dug into this topic and talked to people about it, I’ve noticed that this concern seems to jump immediately to people’s minds as a reason cryonics is unlikely to work out.

They ask: “There will be enough problems on Earth to deal with—do you really think people are going to care about bringing dead people back to life?”

Cryonicists have answers to this question.

First, they point out that patients won’t be floating in tanks in a world that has forgotten them. Rather, as a patient, you’d likely have A) descendants or friends who will be highly aware of you and eager to see you reanimated, B) the larger cryonicist community, who will be as passionately interested in your fair treatment as PETA activists are in the fair treatment of animals, and C) the contractual obligation of your future care-takers—similar to how today you might be operated on by a surgeon who doesn’t know you, but who diligently cares for you anyway out of professional obligation.

Second, they argue that once the revival of cryonics patients becomes a reality, the public’s conception of what a cryonics patient is and what she deserves will dramatically shift:17

Long before it ever becomes possible to contemplate revival of today’s patients, reversible suspended animation will be perfected as a mainstream medical technology. From that point forward, the whole tradition of caring for people who cannot immediately be fixed will be strongly reinforced in culture and law. By the time it becomes possible to revive patients preserved with the oldest and crudest technologies, revival from states of suspended animation will be something that has been done thousands, if not millions, of times before. The moral and cultural imperative for revival when possible will be as basic and strong as the obligation to render first aid and emergency medical care today.

If a cryonics patient might seem to have the rights of a farm animal today, cryonicists expect that to become an outdated and primitive-seeming viewpoint down the road. They believe cryonics patients will be looked upon more like today’s coma patients.

That sounds great, but of course, we have no idea how the future will play out or what the standing will be for the field of cryonics and its suspended patients. It does seem plausible, at least, that cryonics patients will end up with more and more rights in the future, not fewer and fewer. If that’s what happens, If 4 shouldn’t be much of a problem.

And if all four Ifs go your way, you’ll finally be able to move onto the next step—the one that will really blow your mind when it happens.

Step 9) Be revived

This will be quite the experience.

First, whether it happens 30 years or 2,000 years after you were last conscious, it’ll feel the same to you—probably a bit like a short nap. When you sleep, you feel the passage of time—when you wake up after an eight-hour night’s sleep, it doesn’t feel like you just went to bed a second ago, it feels like it’s been eight hours. But being on pause in your liquid nitrogen thermos is different. You won’t experience the passage of time, so it’ll feel like you were just awake in your previous life (the only reason it won’t feel totally instantaneous is that you’ll have lost your short term memories). You’ll probably be super disoriented, and someone will have to explain to you that A) you’re in the future, and B) the cryonics worked, and you’re no longer a person about to die—you’re healthy and rejuvenated and all set to start living again.

How intense.

As a very not-heaven-believing person, I’ve always thought about how pleasantly shocked I would be if I died and then woke up in some delightful afterlife. I’d look around, slowly realize what was happening, and then I’d be like, “Wait…NO FUCKING WAY.” Then I’d promptly plant myself at the gates and watch other atheists come in for the fun of seeing them go through the same shock.

I imagine being revived from cryonics will be kind of like that. Maybe a few notches less shocking, since you presumably did the cryonics thing because you thought there was a chance it would work—but still a pretty big no fucking way moment.

After the initial shock, you’ll have to figure out what kind of world you’ve woken up into. Some possibilities:

It could suck. You could wake up in a far future world that’s a lot worse than the one you previously lived in and a world in which you know zero people. Even worse, you could wake up in some really scary situation—who knows what kind of creepy shit might be going on in the future.

It could be blah. You could wake up in a world that’s kind of meh. Like it’s not as future-y and cool as you thought it would be and you’re not immortal, just somewhat restored and still vulnerable, and you have to get a job and you don’t really have applicable skills for the times. Just kind of whatevs.

It could be incredibly rad. Probably the most likely outcome, you could wake up and it could be very, very rad. The future-y stuff might be cool and fun beyond your comprehension. You might have previously been 84 and aching everywhere and forgetful, and suddenly you have the body of a perfectly fit 20-year-old, or maybe something even better, like a super-charged synthetic body that doesn’t feel pain or exhaustion and can’t get sick. Your old, forgetful brain could be repaired and full of vitality you haven’t experienced in 50 years. And best, you might be surrounded by friends and family who were also cryopreserved and are unbelievably excited to see you. It could be rad.

It could be even crazier if you wake up in a virtual world after having had your vitrified brain data uploaded to a computer. You wouldn’t feel like you were in a computer—you’d feel every bit as real as you did when you were a human, except now everything is amazing and magical and you can spend almost all your time fulfilling my lifelong dream of sliding down rainbows like this care bear.18

Your friends and family could be there with you, also virtually uploaded but still fully themselves with all of their old memories—all of you now eternal and indestructible, with no need for the physical world or its resources.

Who knows what kind of world you’d wake up in. But a couple things lead me to believe it would be a pretty good situation:

- A really terrible future world probably isn’t the type of world that would be concerned with protecting and reviving cryonics patients. In a world like that, you’d probably just never wake up.

- Likewise, a future that can revive vitrified people is by definition pretty technologically amazing, so it’s hard to imagine waking up in a world that hasn’t solved all kinds of problems our current world suffers from.

- The future tends to be better than the past. Humans have the tendency to predict dystopian futures, but at least so far, it’s been the other way around. Say what you want about the ills of today’s world, but it’s better to be a human today than it was 200 or 1,000 or 10,000 years ago.

But because we have no idea what revival will be like, we have this next step:

Step 10) Decide if you’re into it and want to stay

Barring some hilariously bad scenario where you’re revived into a world of eternal virtual torture with no ability to end it—which really makes no sense—cryonics is a risk-free venture. It has an undo button—just kill yourself and it’s as if it never happened. If you’re not into it, your journey ends here. Otherwise, move on to the next step.

Step 11) Enjoy shit

We’ve kind of reached the end of me guiding you. You’re now just living again like you were before—hopefully in a much better situation—and what you do at this point is really your business. Just go do your thing and enjoy being in the future.

Step 12) Die for real this time

At some point, you’ll be over it. No one ever will ever ever want to live forever, a fact I realized at the end of my Graham’s Number post. When the time comes, I assume the fancy future will have some painless way to bow out—something that will cause total info death, where your data is truly unrecoverable. At that point, you’ll have lived the complete life you want to live, not a life cut short by the limitations of the medical technology of the time you happen to be born in. That’s really the way things should be.

___________

Now that we all know a lot more about cryonics, let’s bring back our sentence. This is where we were, and we were looking closely at the three words in the red:

Cryonics is the morbid process of freezing rich, dead people who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to bring them back to life, and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

We can get rid of “rich,” because at least for younger people, cryonics can be paid for with a not-that-expensive life insurance plan.

We can get rid of “dead,” because cryonics doesn’t deal with dead people, it deals with people currently doomed to die given the technology they have current access to. For the same reason, we can also change the wording of “bring them back to life.”

And we can get rid of “freezing,” because cryonics doesn’t freeze people—it vitrifies them into an amorphous solid state.

While we’re here, let’s get rid of “morbid.” Is a vitrified human head floating in liquid nitrogen morbid? Yes. Is it more morbid than being eaten by worms and microbes underground or being burned to ashes? Definitely not. So not a fair word to use.

So that leaves us with a sentence more like this:

Cryonics is the process of pausing people in critical condition who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to save them, and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

And then there’s the elephant in the room—this part of the sentence: …and the community of hard-core cryonics people might also be a Scientology-like cult.

I put that in there because when you’re examining something that involves A) a fringe community, B) the possible concept of immortality, and C) members paying large sums of money for services that they’re told might pan out 1,000 years from now—you have no choice but to put up your “Is this a Scientology-y thing?” antenna.

One way to let that antenna do its work is to read a bunch of stuff written by smart, credible people who think the whole thing is utter BS. If anything will disenchant you to the excitement of something as out there as cryonics, it’s experts telling you why it should be ignored.

So I did that. And as I read, I weighed what I read against the rebuttal from cryonicists, which I’d often find on Alcor’s highly comprehensive FAQ page. Other resources for the cryonicist viewpoint are the thorough FAQ of the Cryonics Institute’s ex-president, Ben Best, Alcor’s Science FAQ and Alcor’s Myths page.

The people who are super not into cryonics fall into a few general buckets:

Skeptic Type 1: The scientist with a valid argument about why cryonics might not be possible

The mainstream medical community is generally not on board with cryonics. No health insurance company will cover it, no government will subsidize it, no doctors will refer to it as a medical procedure.

Some skeptics make what seem to be valid points. Biochemist Ken Storey says, “We have many different organs and we know from research into preserving transplant organs that even if it were possible to successfully cryopreserve them, each would need to be cooled at a different rate and with a different mixture and concentration of cryoprotectants. Even if you only wanted to preserve the brain, it has dozens of different areas, which would need to be cryopreserved using different protocols.” Storey also points out just how tall an order it would be to “repair” someone damaged by vitrification, explaining that “a human cell has around 50,000 proteins and hundreds of millions of fat molecules that make up the membranes. Cryopreservation disrupts all of them.” (Alcor calls this statement patently false.7)

Others point to the towering challenge of either repairing a human brain or scanning one in order to upload it. Brazilian scientist Miguel Nicolelis emphasizes that the task of scanning a human brain would require, with today’s technology, “a million electron microscopes running in parallel for ten years.” Michael Hendricks, who studies the brains of roundworms, believes the challenge of reviving the qualities that make someone who they are is far too complex to achieve, explaining that “while it might be theoretically possible to preserve these features in dead tissue, that certainly is not happening now. The technology to do so, let alone the ability to read this information back out of such a specimen, does not yet exist even in principle.”

Cryonicist response: Totes

Cryonicists don’t really disagree with these people (Storey’s quote notwithstanding). They readily admit that the challenges of reviving someone from cryopreservation are insurmountable using today’s technology. They simply point out that A) there’s no scientific evidence that cryonics can’t work, B) we shouldn’t underestimate what future technology will be able to do (imagine how mind-blowing CRISPR would be to someone in the year 1700 and think about what the equivalent would be for us), and C) there have been some promising developments—like the recent well-preserved vitrified rabbit brain news—that suggest there’s reason for optimism.

I’m yet to hear a cryonicist say, “Cryonics will work.” They just don’t feel that this is a case where a lack of proof amounts to a lack of credibility. Alcor’s Science FAQ addresses this: “The burden of proof lies with those who make a claim that is inconsistent with existing well-established scientific theory. Cryonics is not inconsistent with well-established scientific theory … At no point does cryonics require that existing physical law be altered in any way.”

Cryonicists also don’t waste an opportunity to point out these quotes:

“There is no hope for the fanciful idea of reaching the Moon because of insurmountable barriers to escaping the Earth’s gravity.” — Dr. Forest Ray Moulton, University of Chicago astronomer, 1932.

“All this writing about space travel is utter bilge.” — Sir Richard Woolley, Astronomer Royal of Britain, 1956

“To place a man in a multi-stage rocket and project him into the controlling gravitational field of the moon…. I am bold enough to say that such a man-made voyage will never occur regardless of all future advances.” — Dr. Lee De Forest, famous engineer, 1957

Skeptic Type 2: The scientist who argues that cryonics won’t work even though they know less about cryonics than you do right now having read this post

This is a surprisingly large category of cryonics skeptics. It’s amazing, for example, how many people from the mainstream medical world argue that cryonics can’t work because when water freezes, it causes irreparable damage to human tissue.

Cryonicist response: Agreed—that’s why we don’t freeze people. Please read about what cryonics is before saying more words out of your mouth.

Among the cryonics skeptics who literally don’t get what modern cryonics consists of is celebrity physicist Michio Kaku, someone I normally like, but who in this clip is taken to town by Alcor’s CEO for having no idea what he’s talking about.

Part of the reason most scientists don’t get cryonics has to do with its cross-disciplinary nature. Alcor explains:

Most experts in any single field will say that they know of no evidence that cryonics can work. That’s because cryonics is an interdisciplinary field based on three facts from diverse unrelated sciences. Without all these facts, cryonics seems ridiculous. Unfortunately that makes the number of experts qualified to comment on cryonics very small. For example, very few scientists even know what vitrification is. Fewer still know that vitrification can preserve cell structure of whole organs or whole brains. Even though this use of vitrification has been published, it is so uncommon outside of cryonics that only a handful of cryobiologists know it is possible.

Skeptic Type 3: The cryogenicist who doesn’t want the other cool kids to think he’s friends with cryonics, the weird outsider.

There’s an amusing little one-way rivalry going on between cryogenicists (who, remember, deal with the science of the effects of cold temperatures in general) and cryonicists. Cryogenicists tend to view cryonics like an astronomer would view astrology—or at least, that’s what they say publicly out of caution. They seem to sometimes admit that there could be sound science behind cryonics, but they also know that cryonics lacks credibility with the wider science community and they don’t want to get roped into that reputation problem by association (they also have very little sense of humor about people confusing the words cryogenics and cryonics).

Cryonicist response: Whatevs.

Skeptic Type 4: The person who believes that even if you can revive a vitrified person, it won’t really be them.

This relates to a philosophical quandary I explored in the post What Makes You You? Are “you” your body? Your brain? The data in your brain? Something less tangible like a soul? This all becomes highly relevant when we’re thinking about cryonics. It’s hard to read about cryonic revival, and especially the prospect of “waking up” in a virtual world you’ve been uploaded into, without asking, “But wait…will that still be me?”

This is a common objection to cryonics, but few people will argue with conviction that they know the answer to this question one way or the other.

Cryonicist response: Yeah, we’re not sure about that either. Fingers crossed though.

Most cryonicists have a hunch that you can survive cryopreservation intact (cryonicist Eliezer Yudkowsky argues that “successful cryonics preserves anything about you that is preserved by going to sleep at night and waking up the next morning”) but they also admit that this is yet another variable they’re not sure about. You might even want to consider this a fifth “If” to add onto our list: If what seems to be a revived me is actually me…

Skeptic Type 5: The person who, regardless of whether cryonics can work or not, thinks it’s a bad thing

There are lots of these people. A handful of examples:

Argument: Cryonics is icky.

Typical cryonicist response: Yup, but less icky than decaying underground.

Argument: Cryonics is creepy and unnatural.

Typical cryonicist response: People said the same thing about the first organ transplants.

Argument: Cryonics is trying to play God and cheat death.

Typical cryonicist response: Is resuscitating someone whose heart has stopped playing God and cheating death? How about chemotherapy?

Argument: Cryonics is a scam.

Typical cryonicist response: The major cryonics companies are all nonprofits, the employees are paid modestly and the board members running the company (who are all signed up for cryonics themselves) aren’t paid at all. So who exactly is benefiting from this scam?

Argument: “If you have enough money [for cryonics], then you have enough money to help somebody in need today.” — Bioethicist Kenneth Goodman19

Actual cryonicist response: “If you have enough money for health insurance (which costs a lot more than cryonics), then you have enough money to help somebody else in need today. In fact, if you have enough money for any discretionary expenditure (travel, sports, movies, beer), then you have enough money to help somebody in need today. Of all the ways people choose to spend substantial sums of money over a lifetime, singling out the health care choice of cryonics as selfish is completely arbitrary.”20

Argument: “Money invested to preserve human life in the deep freeze is money wasted, the sums involved being large enough to fulfill a punitive function as a self-imposed fine for gullibility and vanity.” — Biologist Jean Medawar21

Actual cryonicist response: “Nobody would ever imagine calling the first recipients of bone marrow transplants or artificial hearts “gullible and vain”. And what of dying children who are cryopreserved? Cryonics is an experiment, and people who choose this experiment are worthy of the same respect as other participants in high risk medical endeavors.”22

Argument: Cryonics will cause an overpopulation disaster.

Actual cryonicist response: This is a common one I’ve heard in my discussions. Here’s what Alcor says: “What about antibiotics, vaccinations, statin drugs and the population pressures they bring? It’s silly to single out something as small and speculative as cryonics as a population issue. Life spans will continue increasing in developed parts of the world, cryonics or not, as they have done for the past century. Historically, as societies become more wealthy and long-lived, population takes care of itself. Couples have fewer children at later ages. This is happening in the world right now. The worst population problems are where people are poor and life spans short, not long.”23

Argument: But Ted Williams.

Let me explain. There are a handful of famous people signed up for cryonics, like Ray Kurzweil, nanotech pioneer Eric Drexler, and celebrities like Larry King, Britney Spears, Simon Cowell, and Paris Hilton.24 But there are very few big names among the 300 or so who are already vitrified. One that is is baseball legend Ted Williams.

Williams is the first thing that comes to mind when a lot of people think about cryonics, an unfortunate fact that cryonicists wish would go away, because his story is mired in scandal (two of Williams’ children said cryonics is what he wanted while the other claimed he wanted to be cremated and the son was just cryopreserving him so he could later profit off of his DNA samples). The ugly story ended up, fairly or unfairly, as a stain on the cryonics industry in many people’s heads, partially because in the midst of it, Sports Illustrated published an article about the scandal with quotes from an ex-Alcor employee accusing Alcor of mismanaging the Williams vitrification, among other things.

Typical cryonicist response: Unfairly. It’s a stain unfairly. The accusations weren’t based in reality, and the employee recently admitted in court that what he said may not have been true.

Argument: Life is long enough. People aren’t supposed to live longer than we do now. Just enjoy what you’ve got.

Typical cryonicist response: Thank you for your opinion. I disagree.

So how does my Scientology antenna feel after reading about 50 skeptic opinions?

Well, the skeptics definitely helped me appreciate the magnitude of the challenge at hand with cryonics. Science has a long way to go before cryonics can truly function as a pause button instead of a stop button—and we may never get there.

But it left me feeling every bit as confident that cryonics is a worthy pursuit and possibly a total game-changer. The fact that cryonic revival seems plausible, coupled with the fact that through most of history, the people of the time couldn’t have even imagined the magic that future technology would make real, makes me feel like the safer bet is on cryonics eventually working. If something important isn’t impossible, the future will probably figure out a way to make it happen, with enough time.

There’s also the “why the fuck not?” argument cryonicists make that’s very hard for skeptics to thwart.

Pro-cryonics scientist Ralph Merkle says it well:25

The correct scientific answer to the question “Does cryonics work?” is: “The clinical trials are in progress. Come back in a century and we’ll give you an answer based on the outcome.” The relevant question for those of us who don’t expect to live that long is: “Would I rather be in the control group, or the experimental group?” We are forced by circumstances to answer that question without the benefit of knowing the results of the clinical trials.

The only way to shoot down a response that says, “We don’t know but we might as well try” is to say, “There is definitely no point in trying because it’s impossible.” And very few credible scientists would claim to have that conviction about things as mysterious as the workings of the brain and the possibilities of the far future.

The other thing that struck me as I learned about cryonics is that cryonicists aren’t usually “salesy” at all when they talk about cryonics. The impression I got from my research is that cryonicists tend to be well-educated, rational, realistic, and humble about what they know and don’t know. They readily admit the problems and shortcomings of the field8 and they’re careful to use measured, responsible language so as not to distort the nuances of the truth.9 And despite a general lack of support from the mainstream medical community, plenty of reputable scientists have become fervent cryonicists.

So, for now, cryonics has satisfied my Scientology antenna.

Which shortens our sentence to this:

Cryonics is the process of pausing people in critical condition who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to save them.

The final wording in the sentence that I’d like to challenge is:

Cryonics is the process of pausing people in critical condition who can’t accept the concept of death, in the hopes that people from the future will be able to save them.

This is the part of the sentence that carries a twinge of eye-rolling contempt—something people often feel when they hear about someone with a desire to conquer mortality. Aside from the aversion we have to the prospect of a human body floating in a freezing tank, many of us feel a distaste towards the motivation behind cryonics. It seems greedy to want more than your one standard life.

I’m not one to typically feel contempt at something like this, but early in my research, even I found myself doing a little head shake when I read about billionaire Peter Thiel signing up for cryonics a while back.

But this post has forced me to take a big step back—back to where I can see death not as a moment but as a process, back to where I can see the human lifespan as a product of our times, not our biology, and back to where I see the concept of human health spread out along the spans of time and where I can imagine how future humans will see our current times of helplessness in the face of biological deterioration.

From way out here, it hits you that we’re living in a phase—a sad little window that an intelligent species inevitably passes through, when they’re advanced enough to understand their own mortality, but still too primitive to save themselves from it. We grapple with this by treating death like a tyrannical overlord we wouldn’t dare try to challenge, not even in our own private thoughts. We’ve been universally defeated and dominated by this overlord for as long as we’ve existed, and all we know how to do is bow down to it in full resignation of its power over us.10

Future humans who have one day overthrown the overlord will look at the phase we’re in and our resulting psychological condition with such clarity—they’ll be sad for us the way we’re sad for brainwashed members of an ancient cult who commit mass suicide because the master has instructed it.

Our will isn’t broken when it comes to resisting the overlord—that’s why we see it as honorable to fight cancer till the final minute, heroic to risk your own life for a good cause and make it out alive, and a terrible mistake to resign to the overlord prematurely and commit suicide.

But when it comes to defeating the overlord, our will has been squashed by a history that tells us that the overlord is indestructible.

And this explains the divide between how cryonicists feel about cryonics and how the rest of us view it. The divide is for two reasons:

1) Cryonicists view death as a process and consider many people who are declared dead today to still be alive—and they view cryonics as an attempted transfer of a living patient to a future hospital that can save his life. In other words, they view cryonics merely as an attempt to resist the overlord, no different than the way we view someone being transferred to a hospital in a different location which has better treatment options for their condition. Most of us, by contrast, view death as a singular moment, so we see cryonics as an attempt to bring a dead person back to life—i.e. we see cryonics as an attempt to defeat the overlord. When cryonicists see us cheer on a billionaire who fights cancer and shake our heads at one who signs up for cryonics, when they see us praying for someone in a coma and rolling our eyes at someone being vitrified—they see us being highly irrational.

2) Cryonicists view death not as an all-powerful overlord but as a puzzle to be solved. They see humans as an arrangement of atoms and see no reason that arrangement should have to inevitably deteriorate if our scientists can just get better at working with atoms. So for them, trying to defeat death altogether is an obvious, rational mission to undertake. But most of us view death as a fundamental fact of the universe—a mysterious and terrifying shadow that hovers over all living things and that only a naive fool would try to escape from—so instead of cheering on the people trying to solve the puzzle of death, we scoff at them and laugh at them, as if they’re too immature to come to peace with the inevitable.

Looking at this through a zoomed out lens was a big Whoa Moment epiphany for me. Suddenly, I saw the cryonicists’ of the world in the same light as those rare ancient people trying to understand how earthquakes work so they could be best prepared for the next one, and I realized that when I shook my head at Peter Thiel, I was being like one of the hordes of ancient people who worshipped the gods that had punished us with that earthquake and who wanted to burn those rare scientists at the stake for their blasphemous thinking.

I started this post thinking I’d simply write a “mini post” about this little community of cryonicists and what they were trying to do and ended it staring at another example of today’s self-proclaimed science-minded rationalists being tomorrow’s idol-worshippers.

I also saw my conception of end-of-life morality flip itself on its head. At the beginning of my research, my question was, “Is cryonics an okay thing to do?” By the end, the question was , “Is it okay to not sign up a dying child for cryonics, or will future people view that the way we see a parent refusing to allow life-saving medical treatment to their child for religious reasons?”

Cryonics has quickly come to seem not only like a good thing to try, but like the right thing to do.

That’s certainly how Alcor sees it. They say:

The moral argument for cryonics is that it’s wrong to discontinue care of an unconscious person when they can still be rescued. This is why people who fall unconscious are taken to hospital by ambulance, why they will be maintained for weeks in intensive care if necessary, and why they will still be cared for even if they don’t fully awaken after that. It is a moral imperative to care for unconscious people as long as there remains reasonable hope for recovery.

And once you’re looking through that lens, everything we consider normal starts to look crazy.

When Kim Suozzi found out she was dying of cancer at age 23, she signed up to be cryopreserved. She viewed it like trying a new experimental drug that might have a chance to save her when nothing else could—a no-brainer. But her father fiercely resisted the decision,11 Reddit users scorned her for it, and the story was unusual enough to warrant a feature article in the New York Times.

It’s as if Kim was part of a group of the world’s cancer-stricken 23-year-olds as they all walked toward a cliff to fall into the jaws of the overlord, and Kim saw a rope hanging from a higher cliff across the chasm and decided to jump for it because maybe, just maybe, it could pull her to safety. And the Times found that to be so bizarre, and so out there, that they wrote a piece on it. Huh?

From far away, it looks a lot like we’re all on a plane that’s going down, with our only shot at survival being to take a chance with an experimental parachute—and we’re all just staying in our seats.

___________

I’ve decided to take a parachute and jump. I have an appointment set up for early April with a life insurance agent and Alcor member to get set up with a plan. I can boil the decision down to three reasons:

1) I love life. Readers have picked up on my mild obsession with death, which might have something to do with the 55 times I’ve talked about it on this blog. But when they bring it up with me, they refer to it as my fear of death. Which isn’t quite how I feel. It’s more that I really like life. I like doing things and thinking things and I like my family and friends and want to keep hanging out with them if I can. I also really want to see what happens. I want to be there when we figure out the Fermi Paradox and when we discover what dark matter is and when we terraform Mars and when AI takes all our jobs and then extincts all of us. I want to see what the 23rd century is like and see how cool the phones are by then. Being alive is a lot more interesting than being dead. And since I have all of eternity to be dead, it seems logical to stay not dead for at least a while when I have the chance.

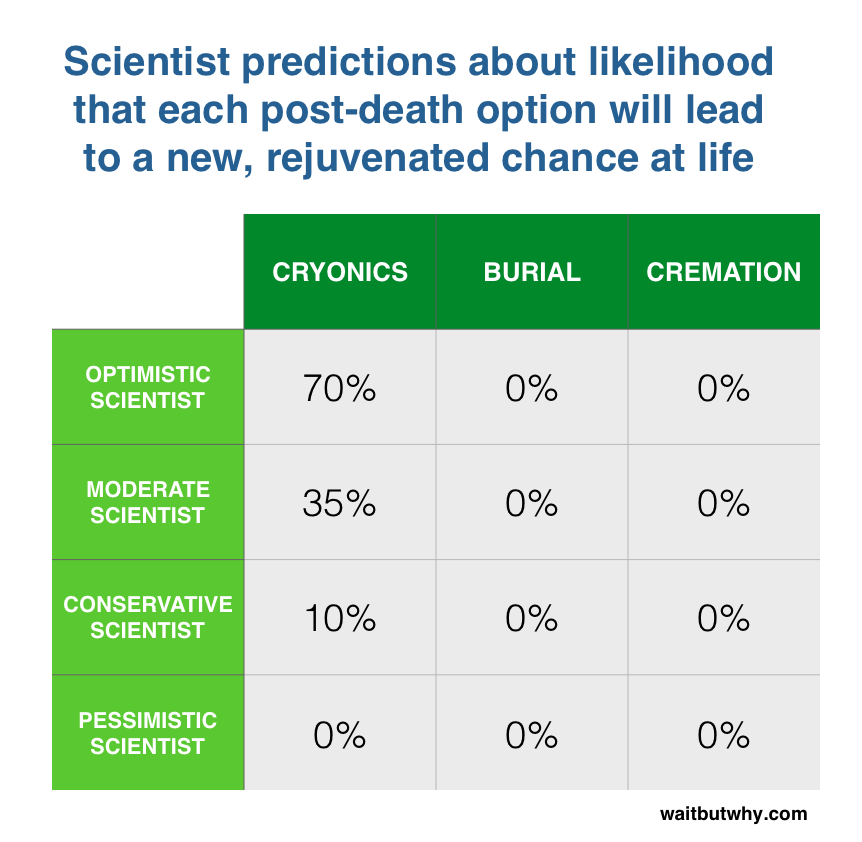

2) This chart.

3) Hope. I’ve always been jealous of religious people, because on their deathbed, instead of thinking, “Shit,” they’re thinking, “Okay here’s the big moment—am I about to blink and wake up in heaven??” Much more fun. And much more exciting. Whether cryonics pans out or not, as I age, at least a little part of me can now be thinking, “I wonder what’s gonna happen when I die?” Atheists aren’t supposed to get to think that. Humans don’t need a huge amount of hope to feel hopeful—they just need something to cling onto. Just enough to be able to have the “So you’re sayin there’s a chance!” feeling.

Some of you will resonate with my decision—others will think it makes me silly, gullible, or selfish.