You’ve probably heard this Seinfeld joke:

According to most studies, people’s number one fear is public speaking. Number two is death. Death is number two. Does that sound right? This means to the average person, if you go to a funeral, you’re better off in the casket than doing the eulogy.

Knowing humans, this shouldn’t be that surprising. I’ve mentioned before that we all have this problem where we’re weirdly obsessed with what other people think of us, so it makes sense that public speaking should be our collective phobia.

But then we also live in a world where public speaking can happen to any of us at any time. Even if you never give an official “talk,” there’ll be some other time when you have to give a big toast at a wedding or present in front of a big group at work or speak at a funeral or some other ceremony. Very few of us are safe.

Over the last couple years, as I’ve done a small amount of Wait But Why-related public speaking, I’ve been able to slowly get over the fear. I’ve learned that if you just be yourself and talk like you normally do, it’s usually received well by the audience, even if you’re clearly nervous.

And that was all fine until August of 2015, when I was invited to do a TED Talk.

The issue is, a TED Talk is not a speaking gig. In a speaking gig, I stand in front of a group of people and say stuff. That’s not what a TED Talk is. A TED Talk is a widely-distributed short film, except the only actor is my face and the only plot is me saying words out of my face and the only choreographer is my nervous pacing and awkward arm-flailing, and instead of a bunch of cuts and different shots and a long editing process, there’s just one do-or-die take, with no second chances.

No, what? No. Obviously not. Who would ever agree to do something like that.

But here’s the problem: Who turns down TED? Not really an option, right? Let’s pause to go through some background:

TED actually started way back in 1984, founded by Richard Saul Wurman, as a small, Silicon Valley annual gathering. The name is an acronym for Wurman’s intention for the focus of the conference: Technology, Entertainment, Design. Through the 1990s, the conference grew both in attendance and in the scope of its topics.

In 2002, media entrepreneur Chris Anderson bought TED from Wurman (through a non-profit he owns) and has run it ever since. He broadened TED’s content focus to “ideas worth spreading,” and in 2006, TED began doing something that would launch the brand into the stratosphere—they put the talks online.

I first heard of TED in 2008, when someone sent me Jill Bolte Taylor’s amazing talk about what she learned from the experience of having a stroke. You probably first heard of TED around the same time. And a few years later, almost everyone knew what a TED Talk was. Anderson describes TED’s rise to global prominence like this:

It used to be 800 people getting together once a year; now it’s about a million people a day watching TED Talks online. When we first put up a few of the talks as an experiment, we got such impassioned responses that we decided to flip the organization on its head and think of ourselves not so much as a conference but as “ideas worth spreading,” building a big website around it. The conference is still the engine, but the website is the amplifier that takes the ideas to the world.1

The TED brand has expanded in a lot of ways, but maybe most notably through TEDx conferences. This can be a little confusing, so here’s the deal: There’s still one annual TED conference, a week-long event in Vancouver, and it’s run by the TED staff. A TEDx conference is independently run, but it has to follow a set of guidelines laid out by TED so that it fits with the overall brand. There are now over 1,500 annual TEDx events that happen in over 130 countries, some of them major, high-profile conferences;1 others tiny and little-known. The best TEDx talks are posted on TED.com, alongside the talks that happen at the main conference in Vancouver.

The thing I was asked to speak at was the big Vancouver one. I say this not only to brag, but also to explain why this whole thing had me freaking out so much. The same thing that made it extra extra scary also made it extra extra not turn-downable.

So I accepted.

As I thought through what I had just committed myself to, I identified a number of concerns, like me not having a topic, or the fact that TED Talks are short and narrow and I tend to be the opposite. But perhaps most worrying was the prospect of this being an Exact Script situation. Let me explain (if you’d rather just read the rest of my TED story, skip down to the comic)—

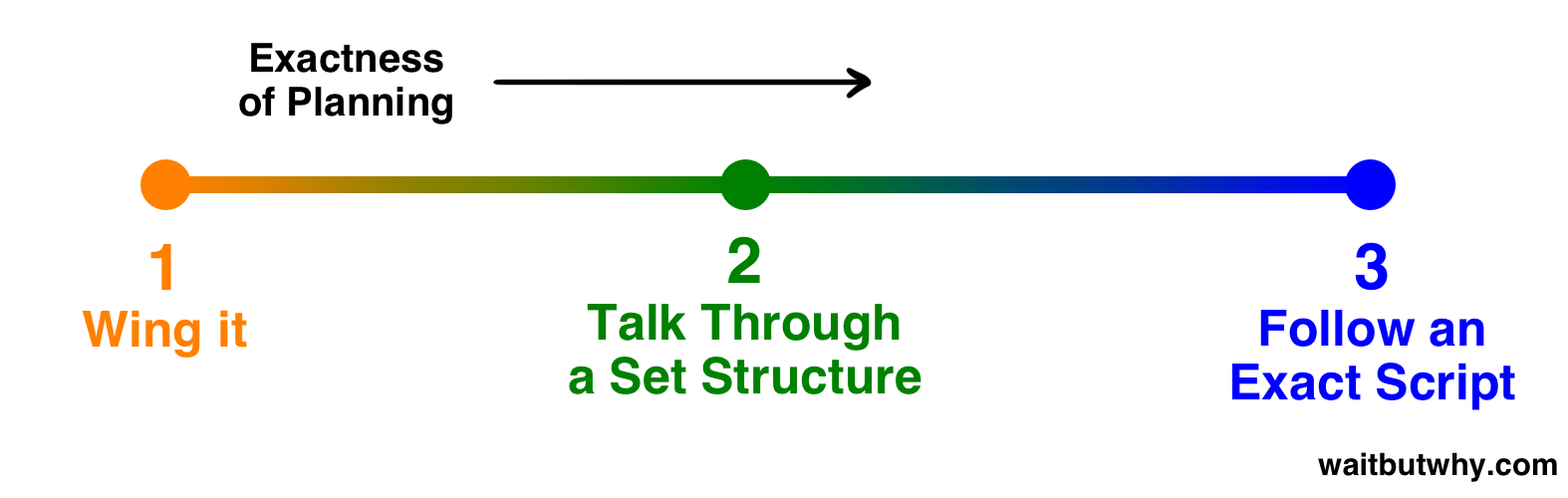

When you speak in public, you have three main options about how to go about it, and they fall along a spectrum:

1) Wing it

At the cockiest end of the spectrum, you have the option of completely winging it. This involves no planning—you just get up there and figure out what you want to say once you’re talking. You be yourself and let the moment carry you.

This takes some hardcore self-confidence, and it only works if you’re really good, and if you’re in the right mood and in front of the right crowd. It’s a really great way to do a really bad talk, and should probably be kept to super-casual things like impromptu dinner toasts.

2) Talk through a set structure

Here, you have a clear structure in your head or a list of bullet points on a notecard, and then you simply talk through it. But importantly, you haven’t scripted sentences exactly—if you did the talk five times, it would come out differently each time, but the general content would be the same. To do this, you have to be super comfortable with the content of what you want to say.

When you use this method, you come off like a human, because you’re actually coming up with real sentences as you go, which is how a normal person talks. Your brain is focused on the content of what you’re saying, and your words are emerging directly from your current thoughts.

This isn’t an exact point on the spectrum but a range. On the left side of the range, closer to the winging it end, you have a few general bullets or slides, but you’ve planned almost nothing beyond that. Toward the right side, you’ve planned out almost exactly what you want to say, including the placement and wording of certain jokes or other key sentences, but it still comes out a little differently each time you do it.

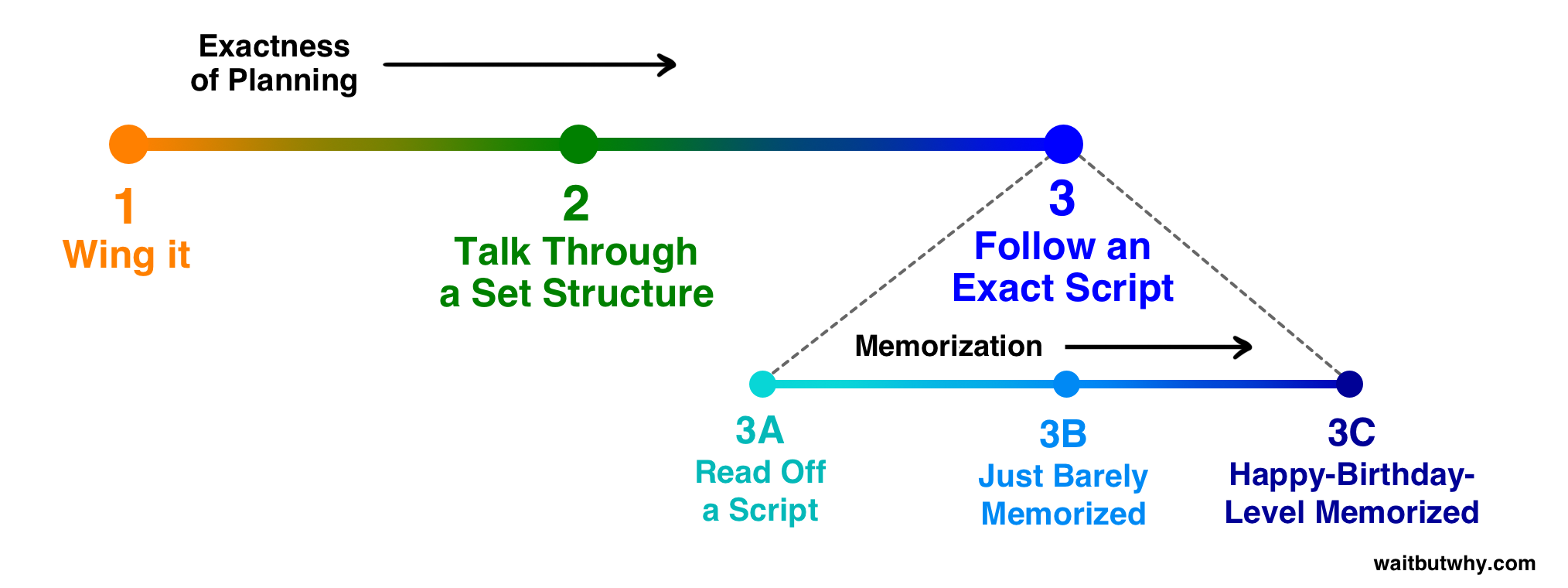

3) Follow an exact script

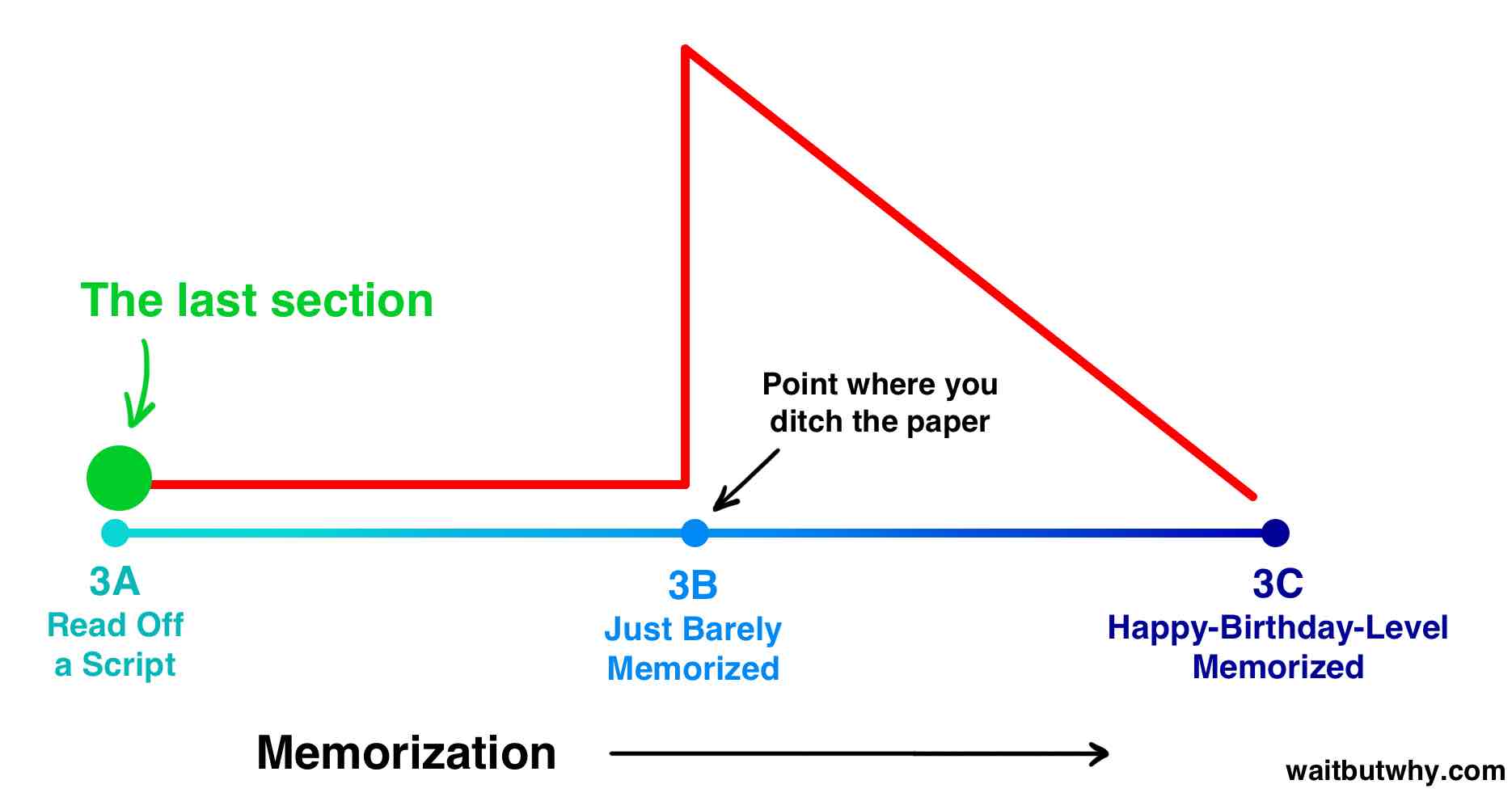

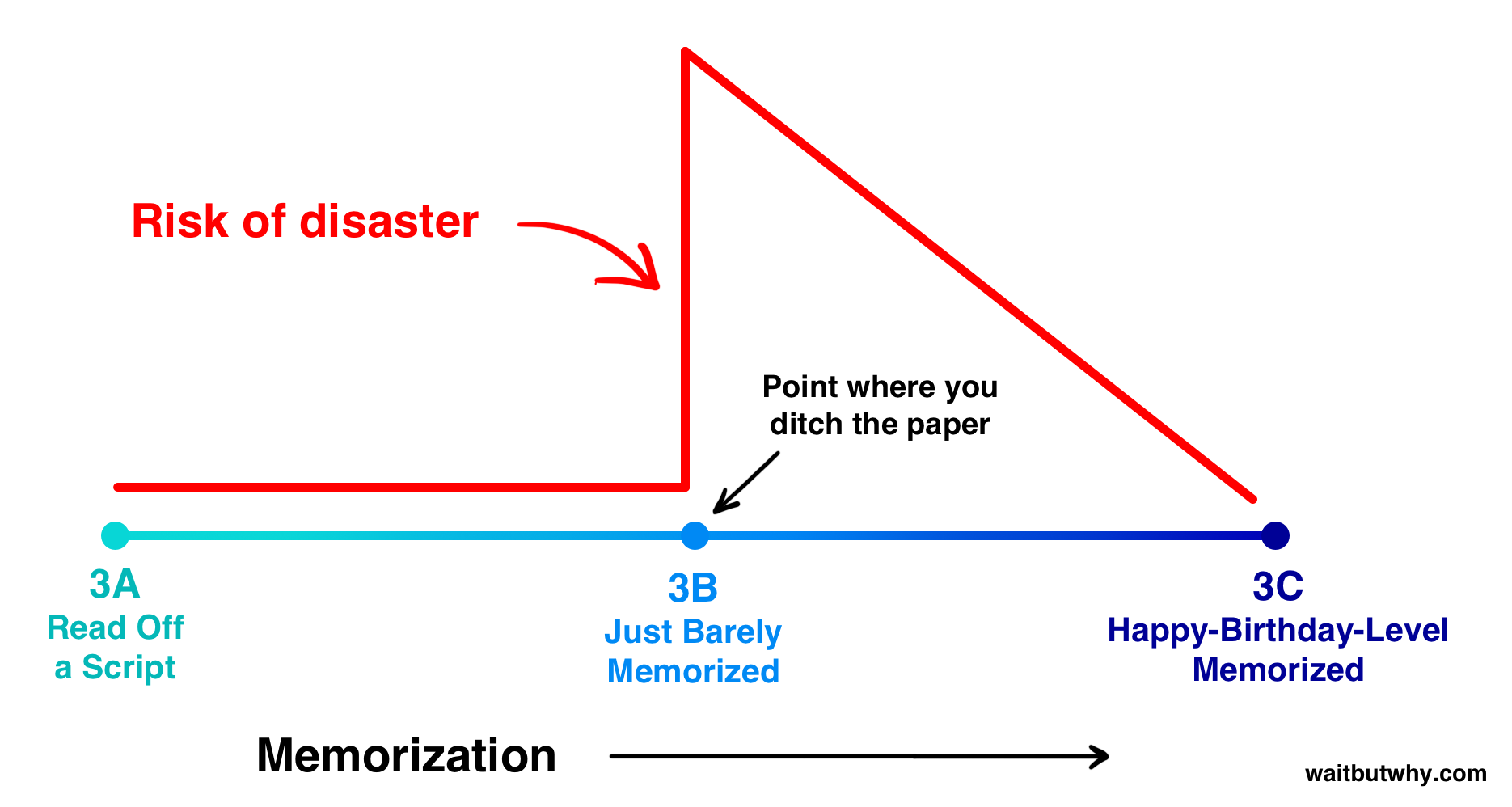

Here, on the other extreme end of the spectrum, you write the exact script of the talk ahead of time and deliver the talk on script, word for word. Some people might immediately assume this method will make a talk impersonal and robotic, but it’s more complicated than that—the exact script method has its own spectrum:

3A) Read off a script

This is simple: You write a script, and the talk is you reading it out loud. During the talk, you’re just acting as the messenger—you’re a functional medium connecting the thoughts of your past self to the present audience.

This is the safest and least stressful way to give a talk and it usually puts the audience to sleep, regardless of how good the content is. Audiences have a fine-tuned radar for when they’re listening to a person say something versus when they’re listening to a person recite something—in the latter case, the speaker isn’t really there in the room with the audience, which has a way of making everyone really want to start playing with their phone.

3B) Just barely memorized

As you move along the scripted spectrum from 3A to 3B, you go from entirely reading, to reading mostly but with some looks up at the audience, to mostly looking up at the audience with some glances down to the paper, to totally memorized with no paper in hand.

A paperless 3B speaker won’t come off much different than a 3A speaker. The 3B speaker isn’t technically reading off of a script, but he might as well be. Because his memorization of the script is fragile, his mind isn’t focused on the content of what he’s saying—it’s focused on reciting the words he memorized. He’ll struggle to make eye contact, and his sentences will come off just robotic enough to make the audience clear that he’s a mostly-unthinking messenger of a written script. Phones will be reached for.

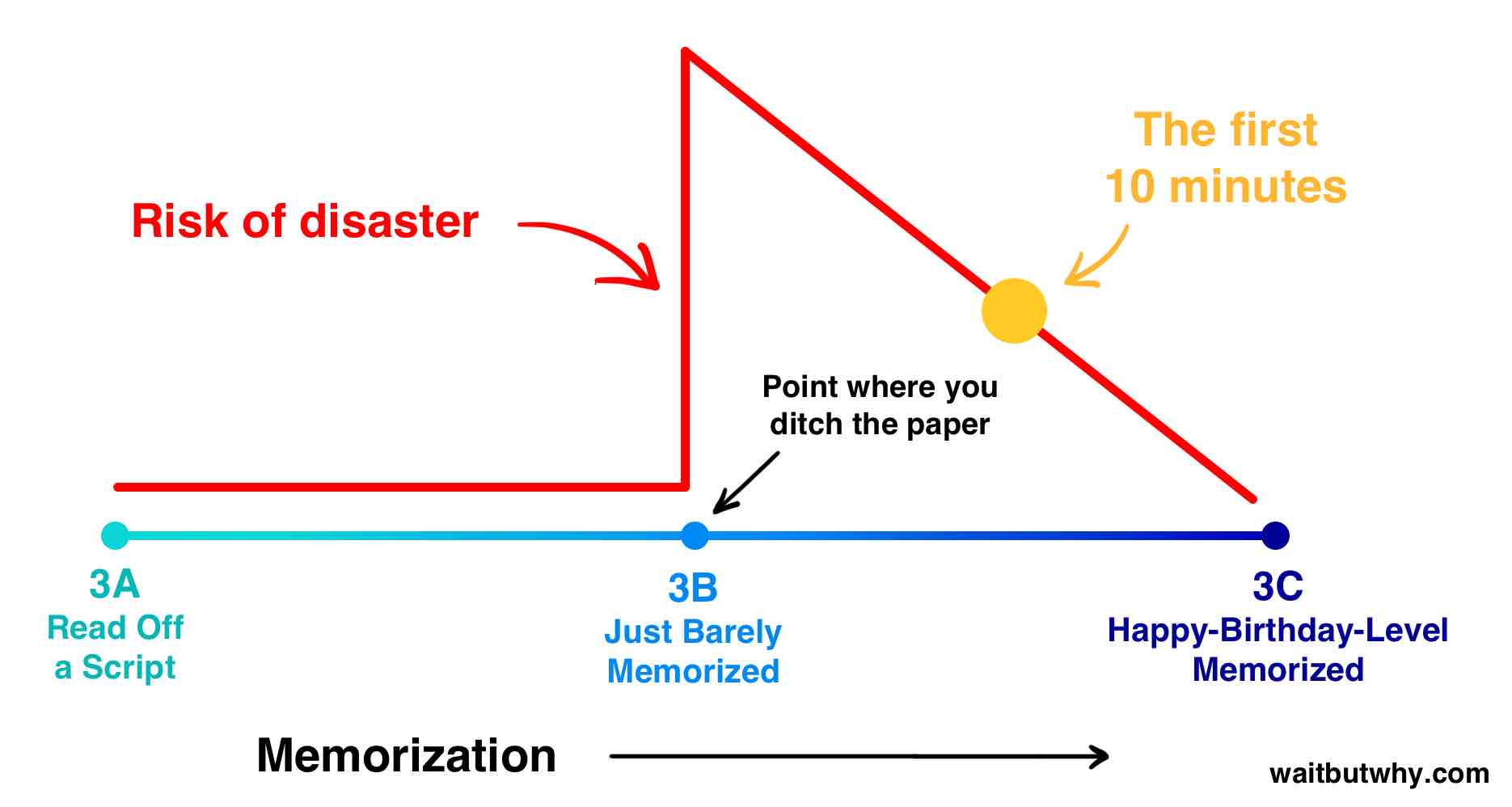

The main difference is that while 3A is the safest method of all, 3B is the riskiest. Going for it without the paper when you only barely have the talk memorized is a great way to disastrously go blank mid-talk.

3C) Happy-Birthday-level memorized

When you get to 3C, you don’t just have the script memorized, you have it memorized cold. And that’s a key distinction. If you’re in a restaurant and your table starts singing Happy Birthday to someone you’re with, you can join in with them even if you’re simultaneously taking a picture of the birthday girl, moving some stuff out of the way so the waiter has a place on the table to put the cake, observing the other people in the restaurant looking over and wishing this wasn’t happening, and four other things. It’s no problem—you can still sing the lyrics. You can do that because the lyrics to Happy Birthday aren’t coming out of your conscious mind—they’re coming out of your subconscious. They’re coming out automatically, and your conscious mind can focus entirely on other things while you’re singing.

That’s how well-memorized 3C is.

The people at TED refer to two tests you need to pass to qualify as Happy-Birthday-level memorized:

- If you record yourself saying the talk and play it back at 2x speed, can you say it out loud while it’s playing and stay ahead of the recording?

- Can you recite the talk with no problem while simultaneously doing an unrelated task that requires attention, like following a recipe and measuring out the ingredients into a bowl?

Memorizing something to this degree might seem like a daunting task, but everyone who’s ever acted in a play has done it. It’s not as impossible as it sounds, because the human brain is able to engrave things to that level if you just rehearse enough and sleep on it enough times.

When a speaker has memorized their talk to this extent, they can be in the room with the audience, even though they’re reciting a previously-written script, because their conscious mind is freed up to think about what they’re saying instead of tied up with the task of remembering which line comes next. This allows the speaker to make eye contact and to bring their live personality into the picture to reflect the words being said in real time.

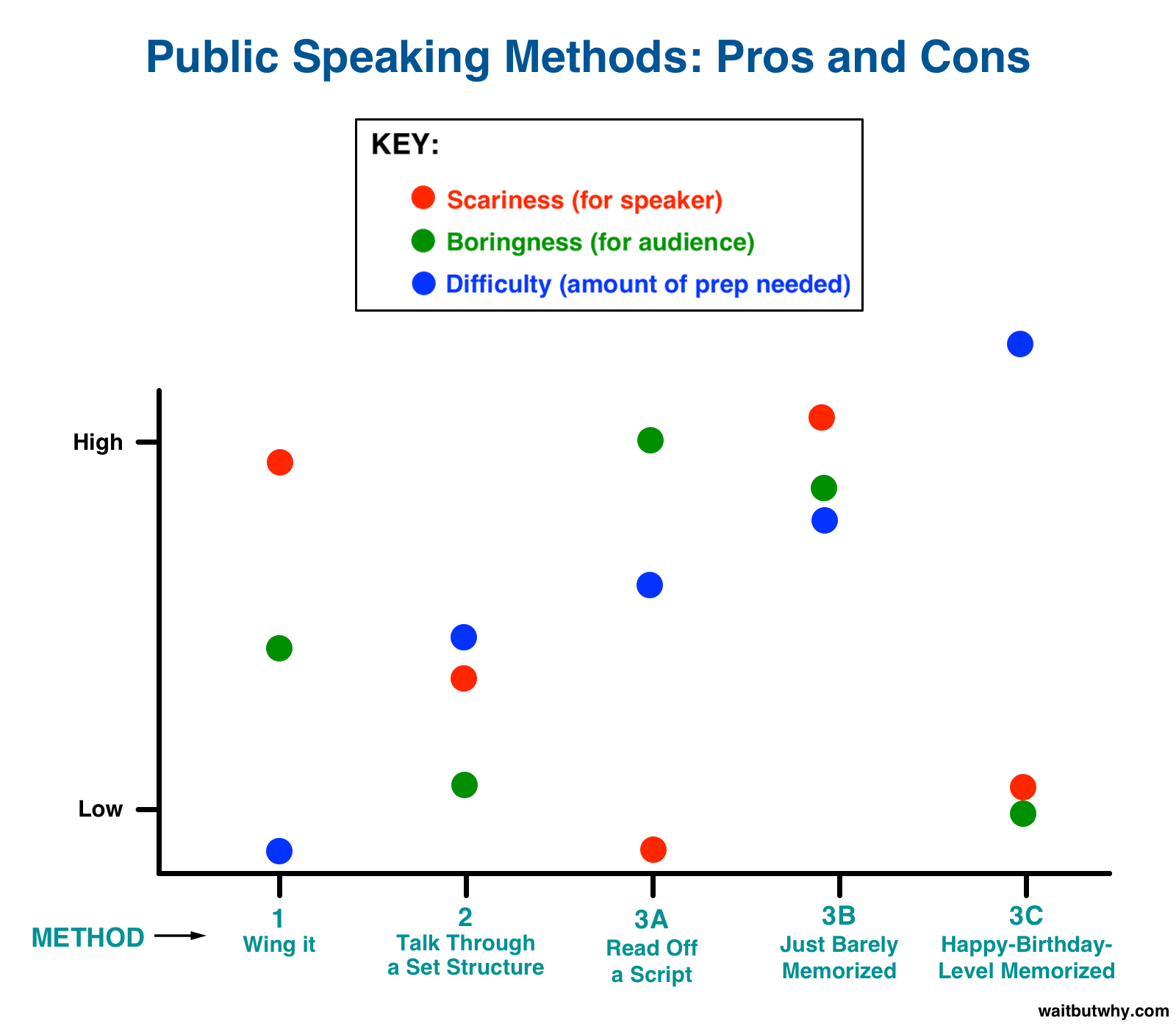

I’d sum up the pros and cons of the five options like this:

On this chart, all three items in the key are bad. Those are the three things that can suck about public speaking. So high-up dots are bad. Looking at this chart, here are some conclusions:

- If and only if the talk is super low-stakes—like an impromptu toast at a group dinner—winging it is a good option. It’s the only method that takes no prep, and it’s also the least robotic, which is perfect in casual situations where seeming like you prepped is awkward. But unless you’re very rad, winging a big talk is a bad idea.

- Method 2 is the best overall choice much of the time, scoring well on all three criteria. It’s not that hard to prep for, you sound like a human, and it isn’t that stressful because with nothing to memorize, there’s nothing to forget, so if you know your material well and you’re feeling confident, things will go fine. The worst case scenario is that you lose your confidence during the talk and flounder through it. That’s a bad outcome, but it’s not a disaster. But Method 2 does require you to be calm and collected, so if you’re really scared of public speaking, it’s probably not the way to go. It also leaves you open to variability—depending on how the words come out, you might deliver a better or worse talk—so if the stakes are super high, it’s not a great option unless you’re a seasoned pro.

- Method 3A—reading off a script—is a pretty bad option, with one huge plus: It’s the least scary by far. For people who are terrified of public speaking, they may just want to cling to Method 3A’s leg and call it a day. But the safety comes at a high cost, in that you’re leaving yourself with almost no chance of delivering a great talk and a high chance of having the audience tune out. It should be noted that in certain high-gravitas situations, when it’s more of an official speech than a talk, the clearly-recited tone of a read speech can be appropriate, and even desired—like a graduation speech. In other cases, someone can be skilled enough at reading a script that they can do so in a human-seeming way. Obama is a good example—you often forget that he’s reading from a teleprompter most of the time you see him talk. But very few of us find ourselves involved with graduation speeches or teleprompters.

- Method 3B—being memorized but just barely—is the worst of all worlds and should never happen. Never ever. If you’re at 3A and you decide to venture into memorization land and ditch the paper, you better be prepared to put in the time to get all the way to 3C, because here’s the deal:

Even if you feel like you have things memorized when you’re alone in your house, once you’re in front of the audience, all of these new factors come into play. Your adrenaline is pumping and super-charging your muscles, your nerves take a shit, and a million new things enter your consciousness—the faces of the audience, the clock ticking down with your time limit, your self-awareness of how you’re standing and what you’re doing with your hands, your regret over messing up a sentence 30 seconds ago. And that well-memorized talk is suddenly not coming to you so easily. 3B is all of the robotic-ness of 3A with none of the safety. Avoid.

Even if you feel like you have things memorized when you’re alone in your house, once you’re in front of the audience, all of these new factors come into play. Your adrenaline is pumping and super-charging your muscles, your nerves take a shit, and a million new things enter your consciousness—the faces of the audience, the clock ticking down with your time limit, your self-awareness of how you’re standing and what you’re doing with your hands, your regret over messing up a sentence 30 seconds ago. And that well-memorized talk is suddenly not coming to you so easily. 3B is all of the robotic-ness of 3A with none of the safety. Avoid.

- When the stakes are high and you want to deliver your best talk—but you’re not a seasoned pro who can pull off Method 2—you’re left with only one option: 3C. You have to write a great script and memorize it cold. 3C gives everyone an option of basically ensuring that you give a great talk, with relatively low risk. You only have to do one thing: spend eternity prepping. 3C takes forever. Writing a great script means working on it a ton and carefully honing every sentence, and memorizing it to Happy Birthday level takes a huge amount more time. You’re essentially writing a play, casting yourself, and then learning the part well enough to act it on a stage with no fear of forgetting your lines. Preparing to this level is a nightmare—but if the stakes are high enough, it’s worth the time.

- A quick note on wedding speeches. The best wedding speeches are usually Method 2 speeches, but most people are too scared to do that. But because they also don’t want to put that much effort into a wedding speech, most wedding speeches end up in 3A and 3B territory—which is why they’re usually pretty lame and boring and come along with a buzz of people quietly talking at the tables in the back. If you’re asked to give a wedding speech, don’t be a dick—it’s someone’s wedding. Either gather the guts to speak from the heart and go with Method 2, or put in the time it takes to get to 3C.

Back to my situation. Over the past couple years, I had begun to find a groove doing not-that-high-stakes 30-to-60-minute talks using the off-the-cuff Method 2, but TED is both far higher stakes than normal and has a strict 14-minute time limit2—meaning you need to be ultra concise and make every word count—so no way I was risking it with Method 2. I was scripting it and going to Happy Birthday land. I found that 90% of other TED speakers do the same thing.

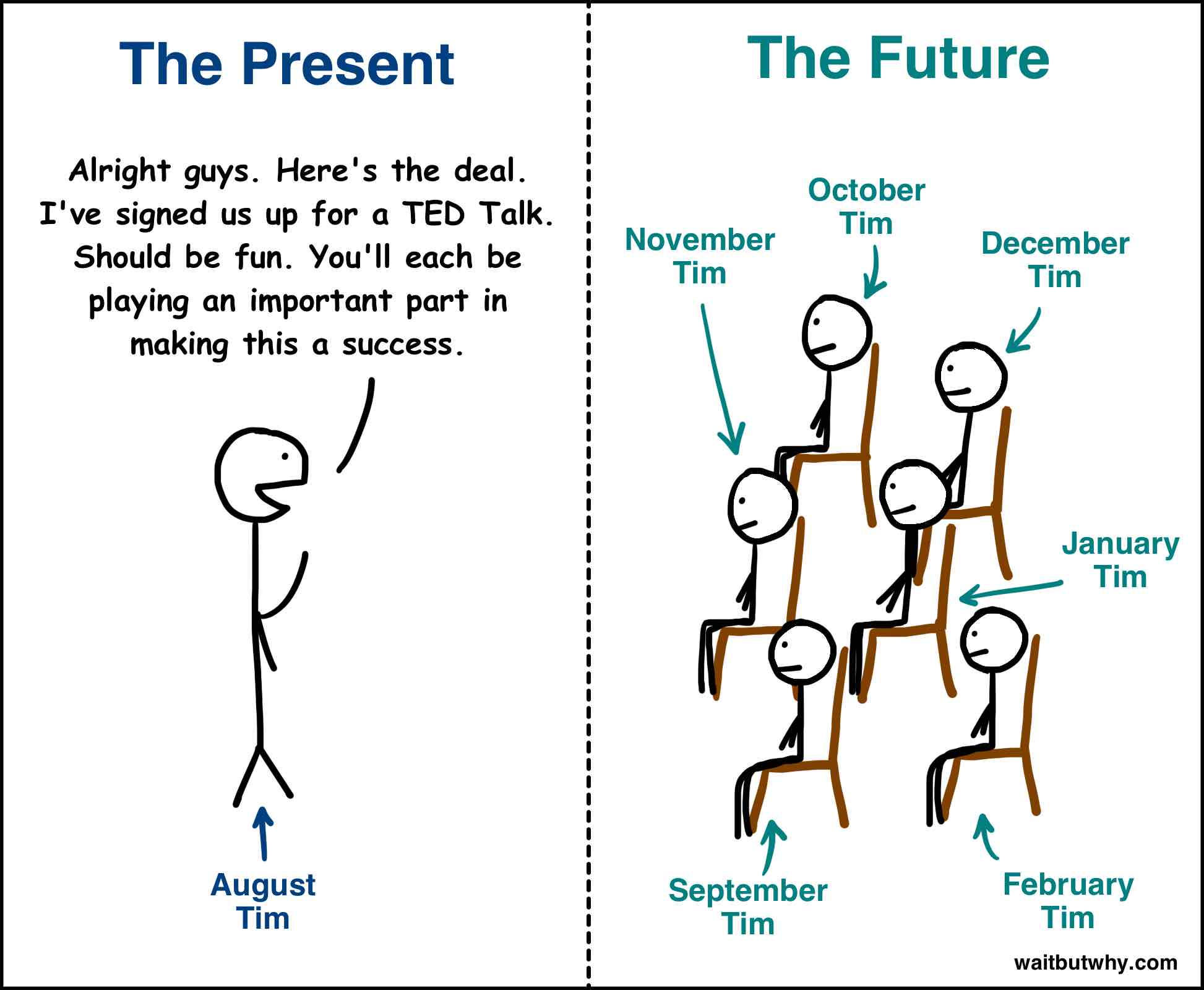

This was gonna be a huge project.

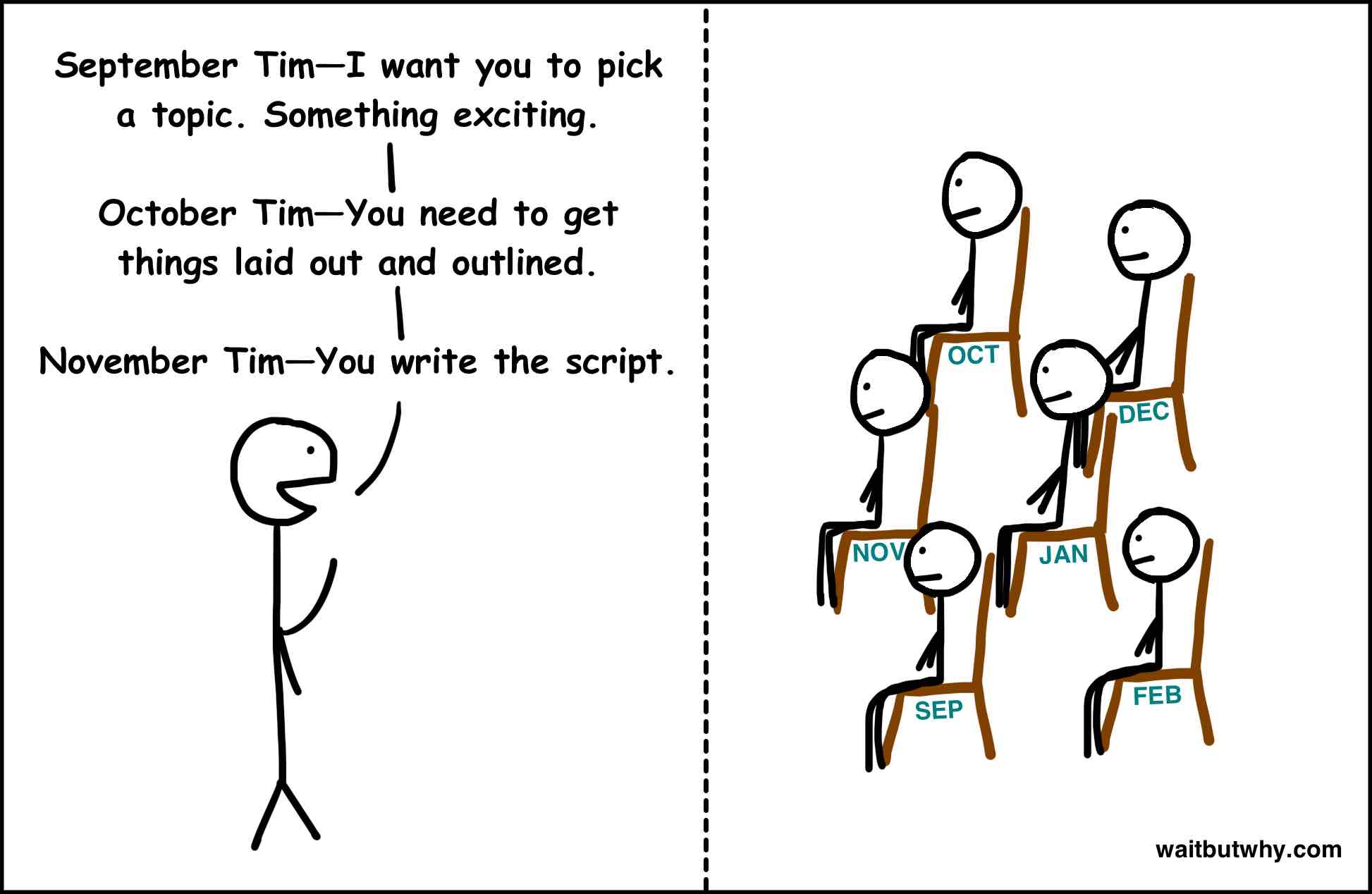

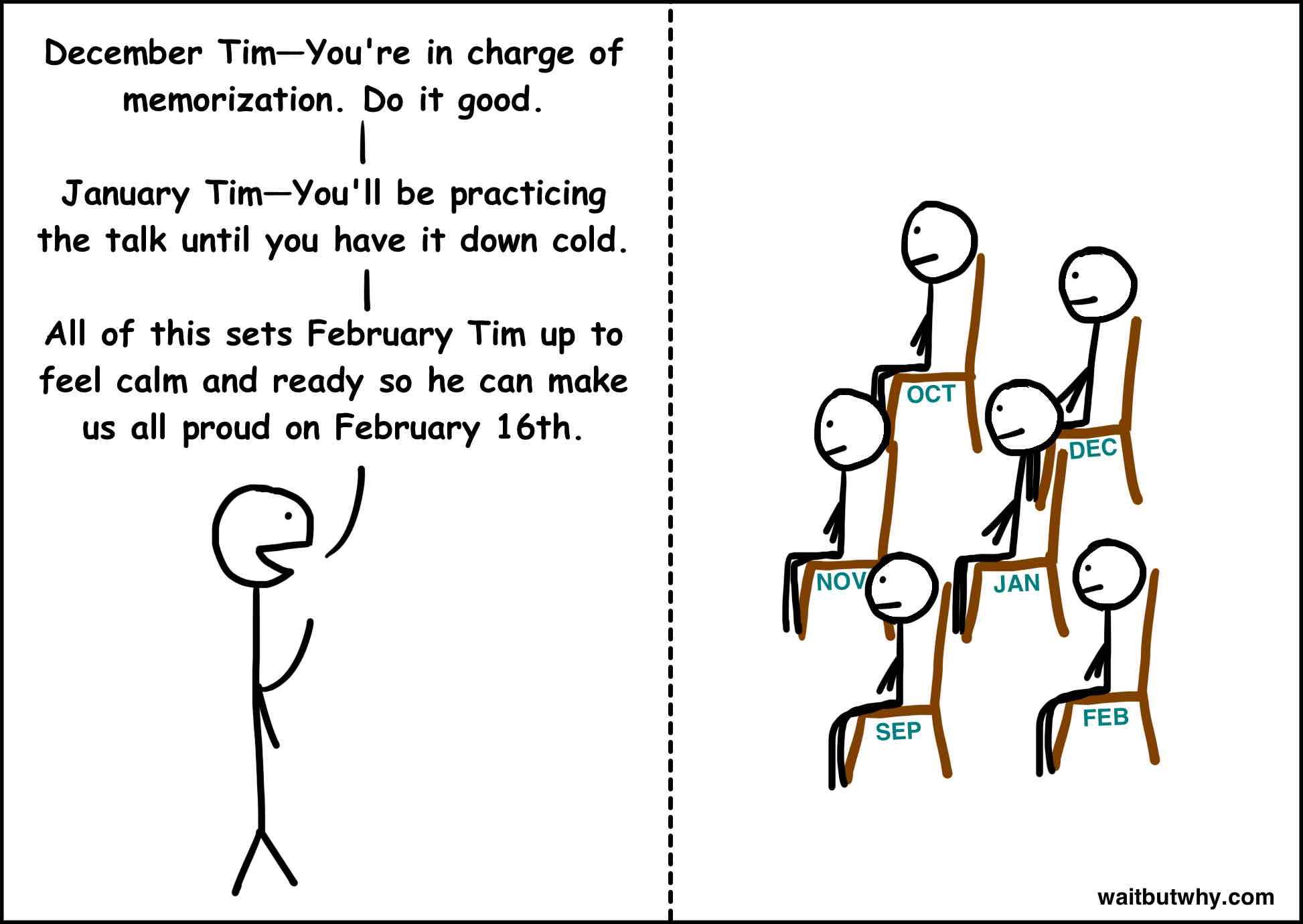

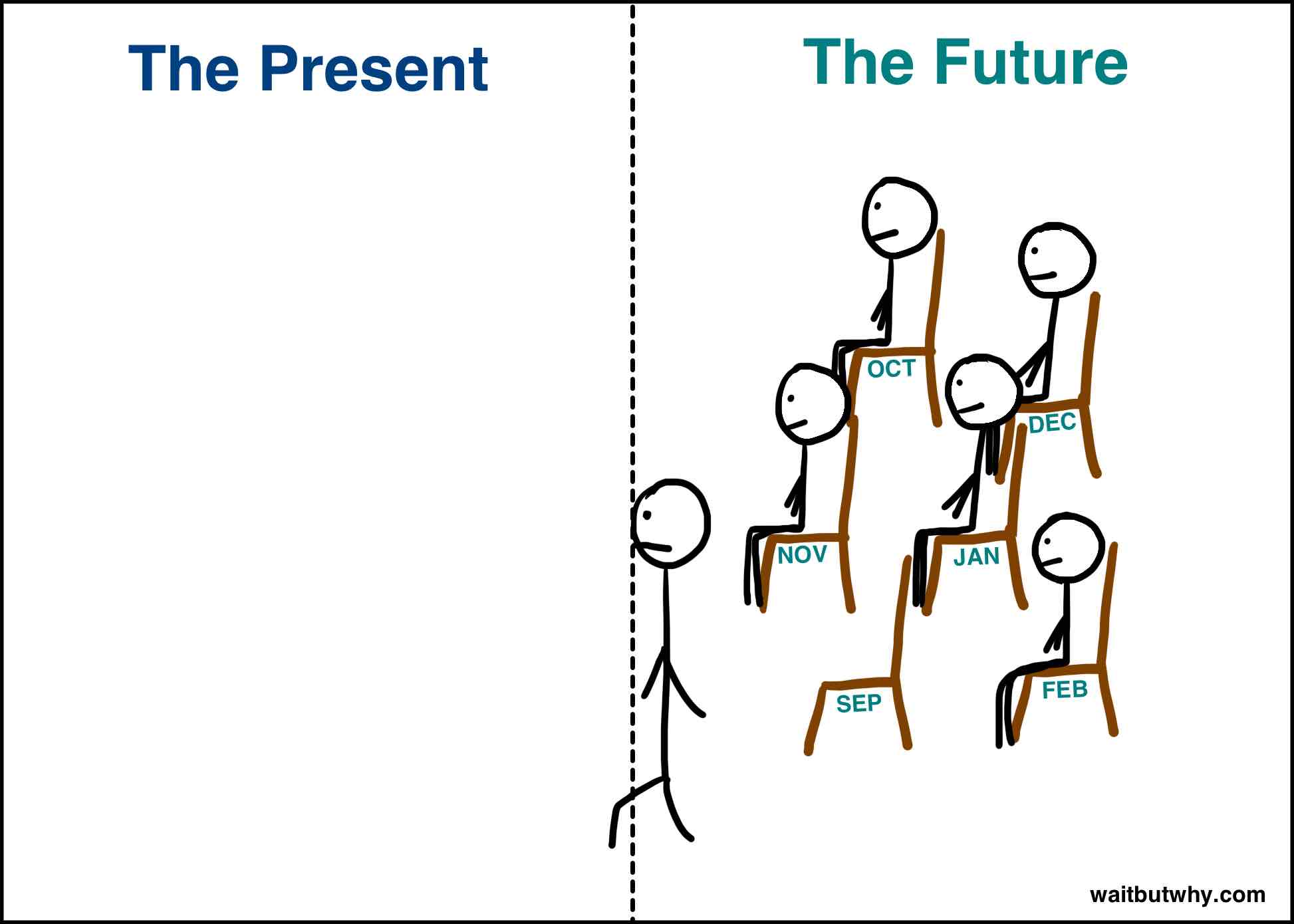

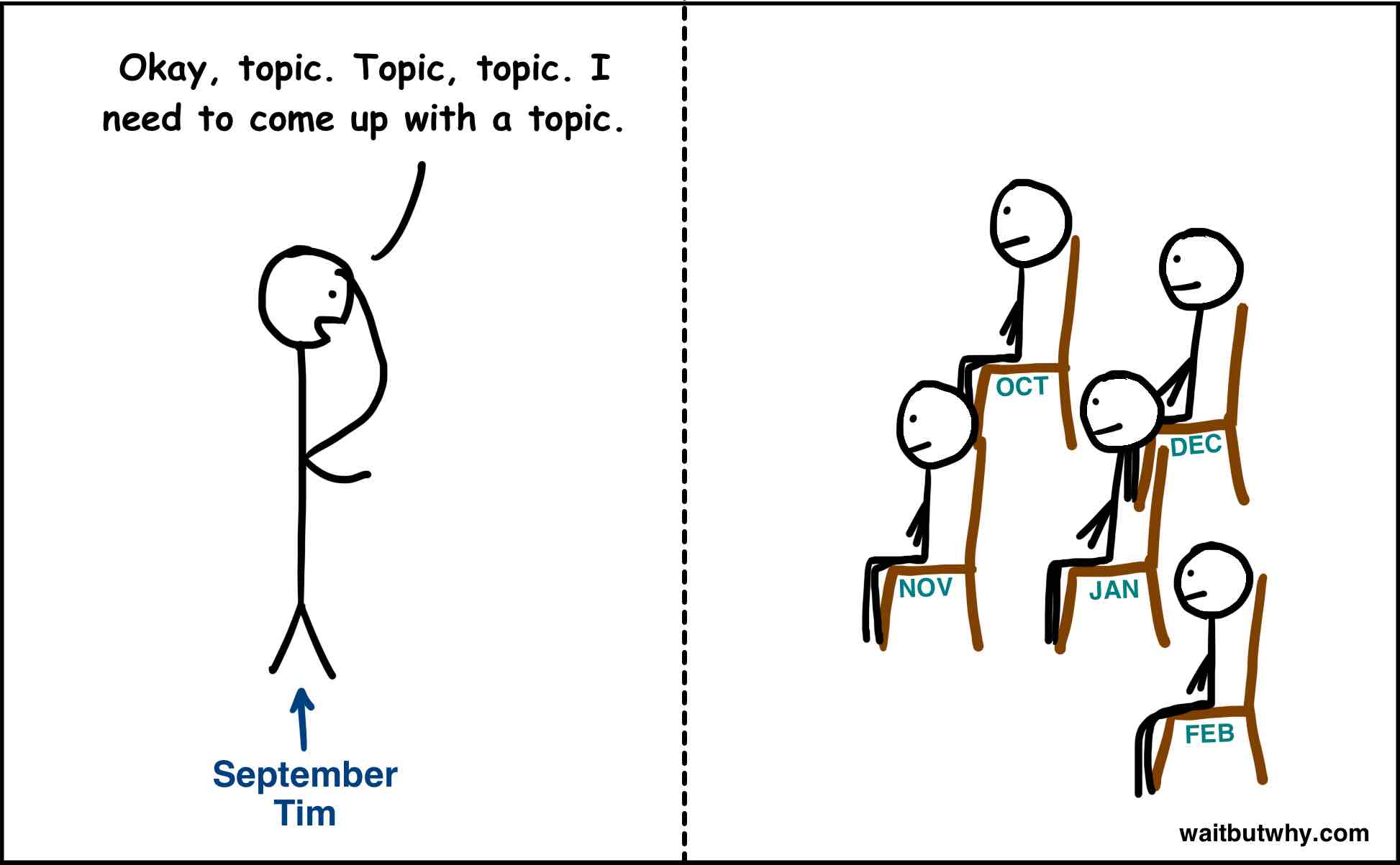

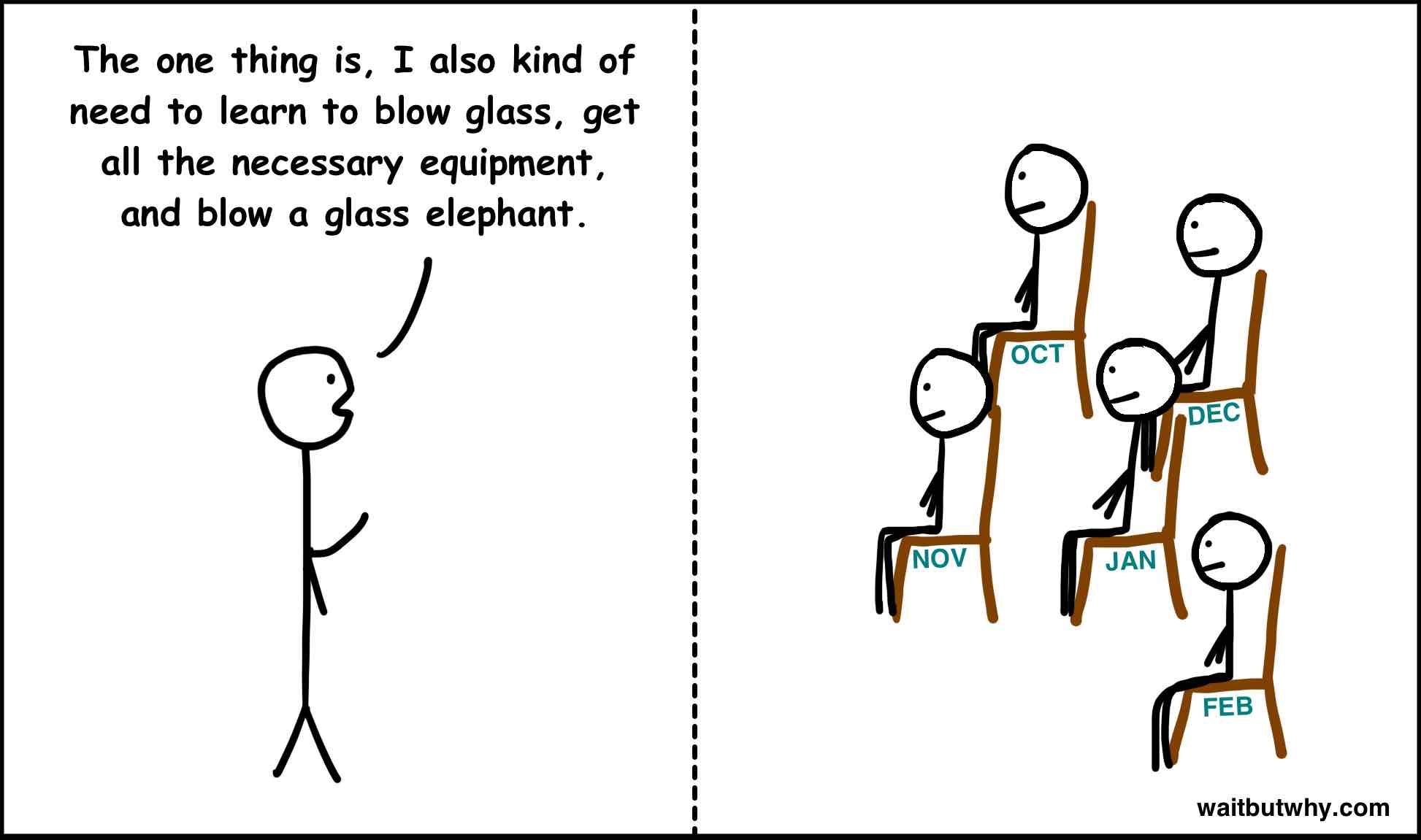

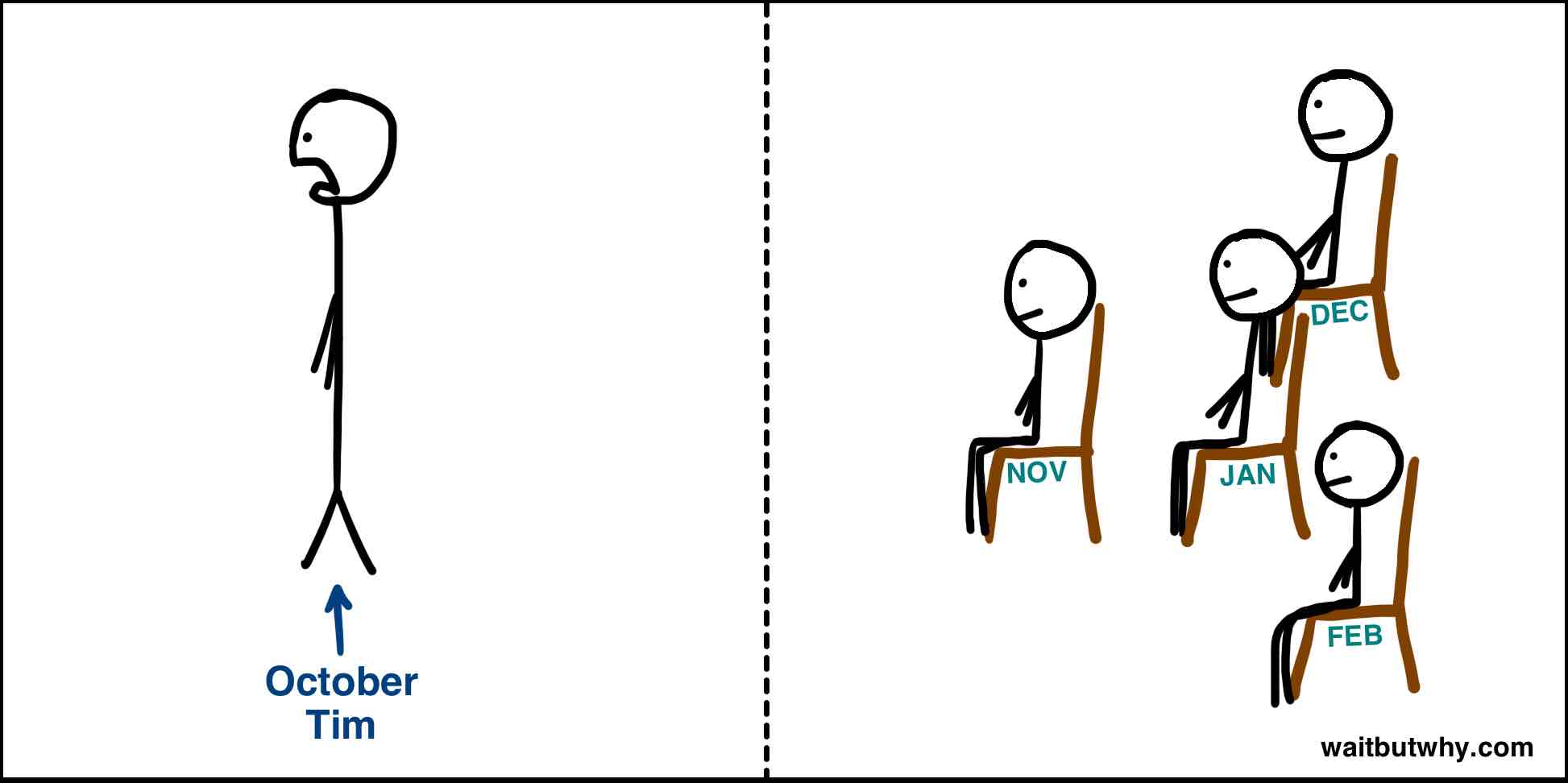

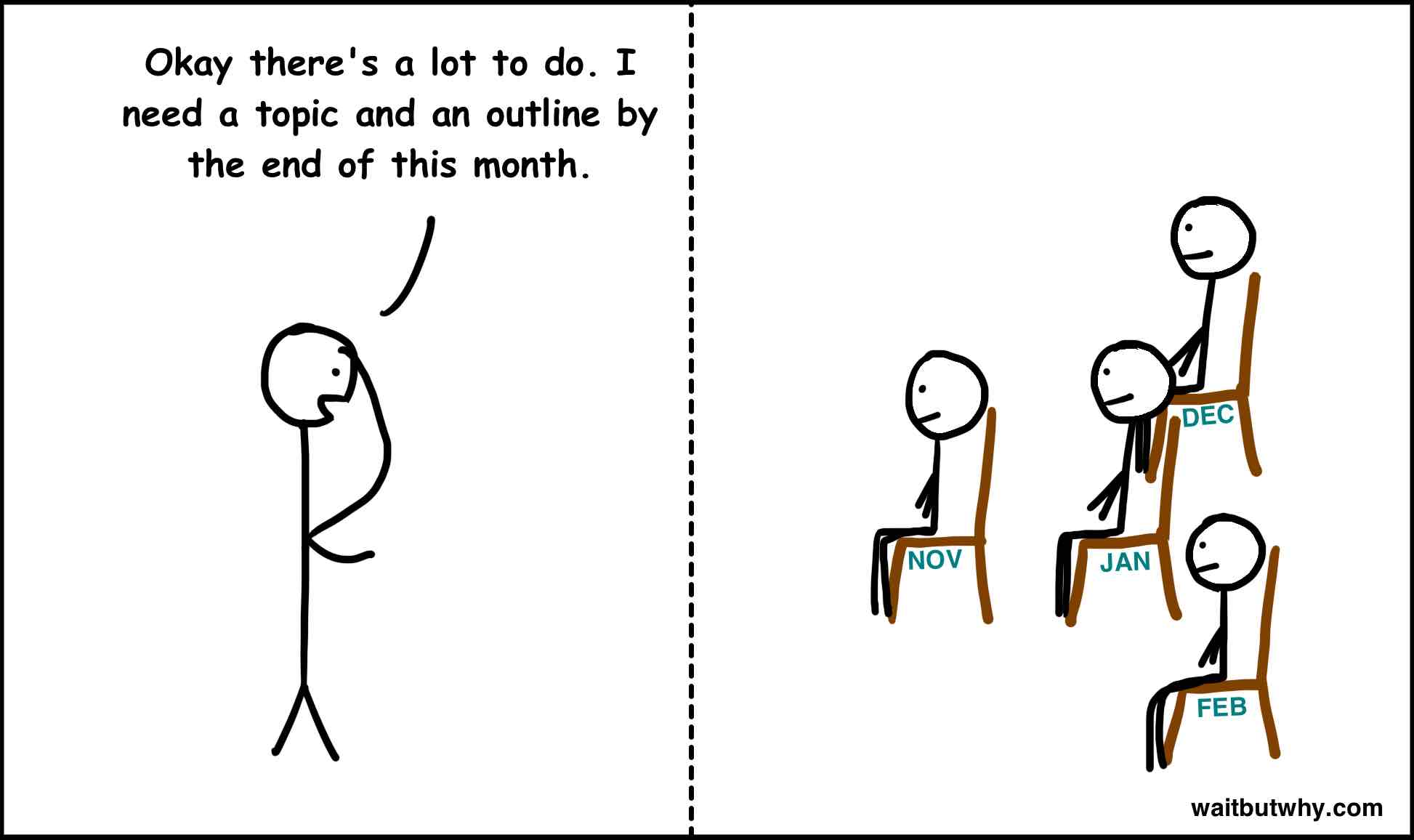

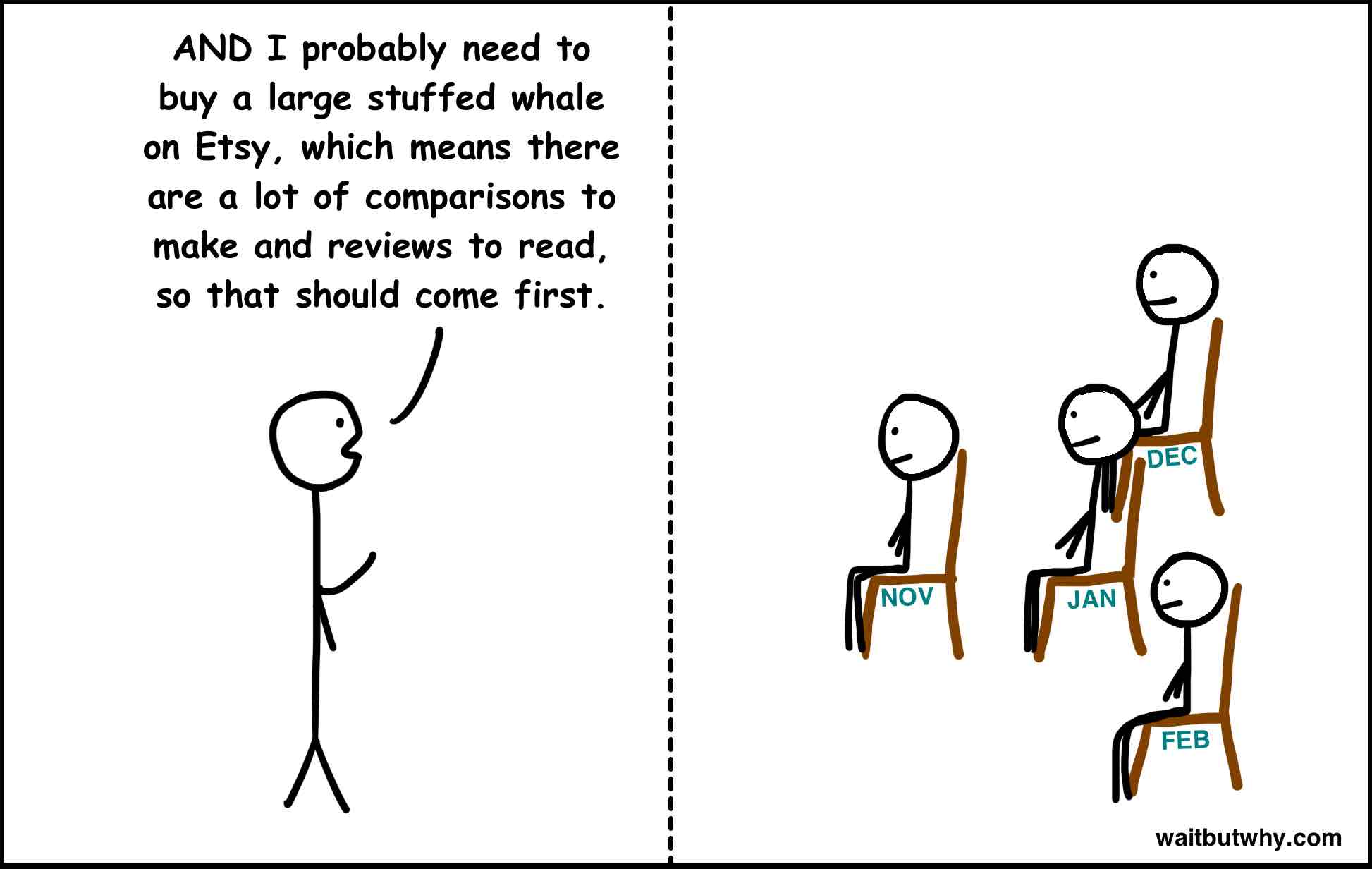

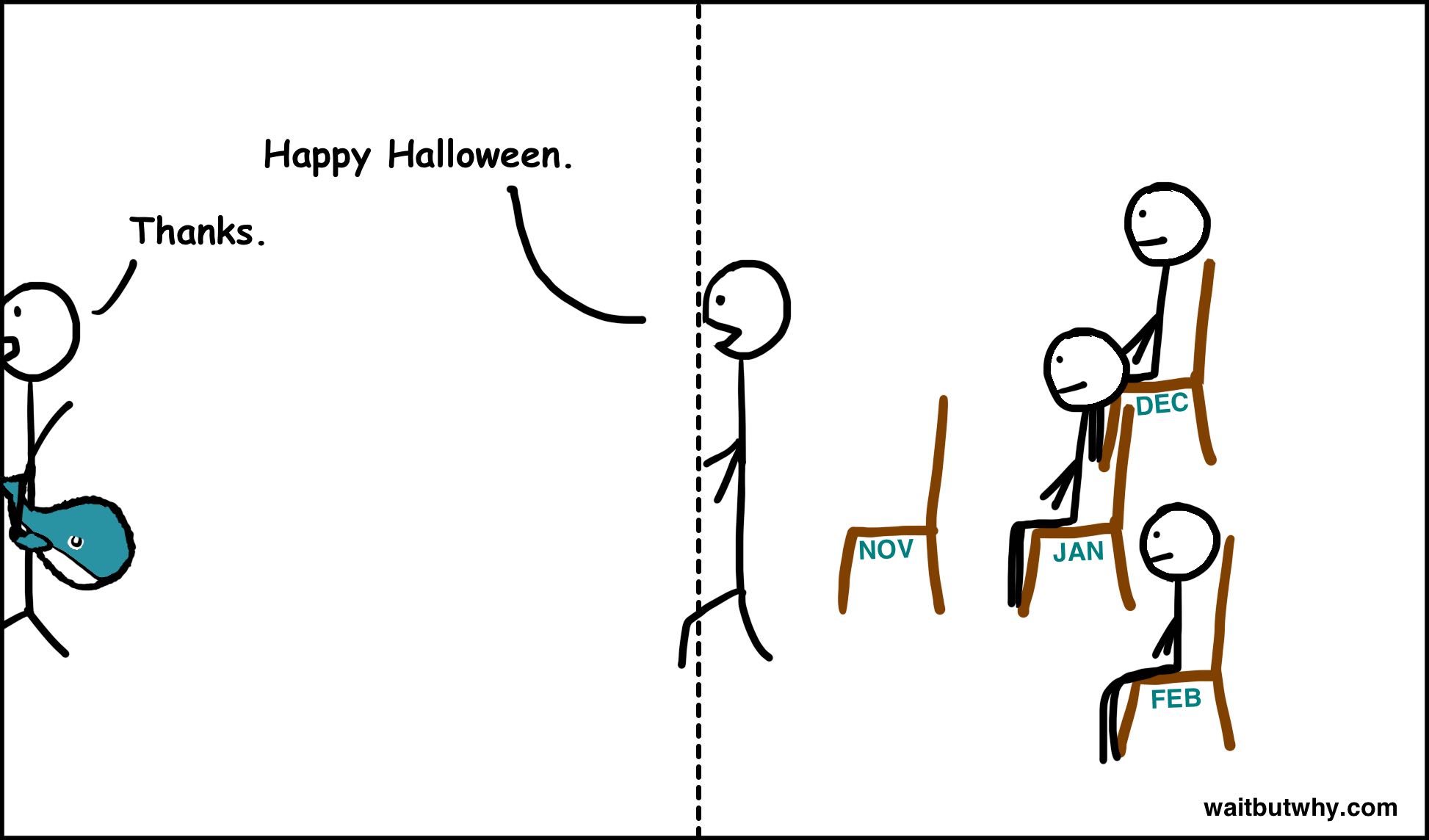

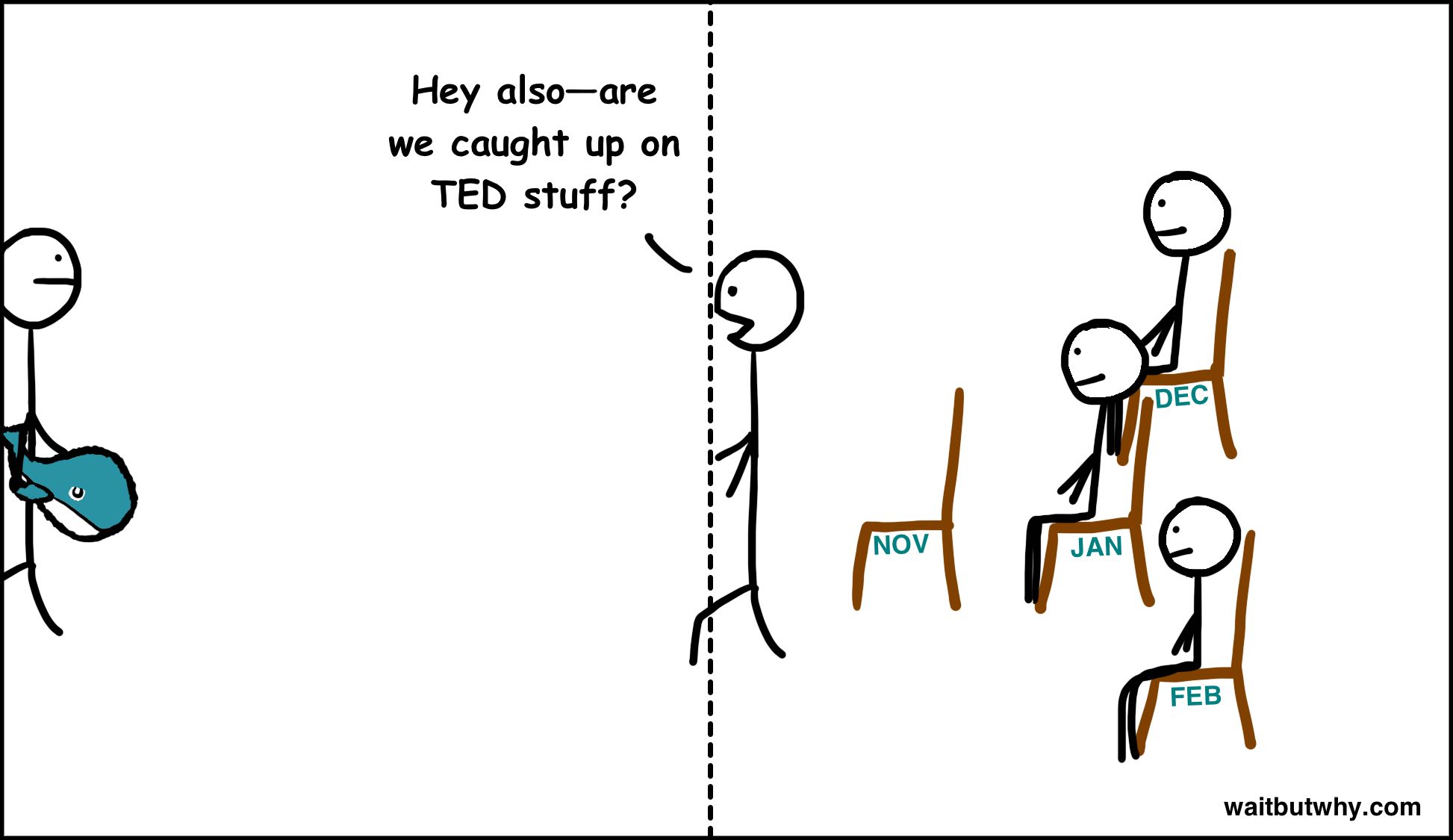

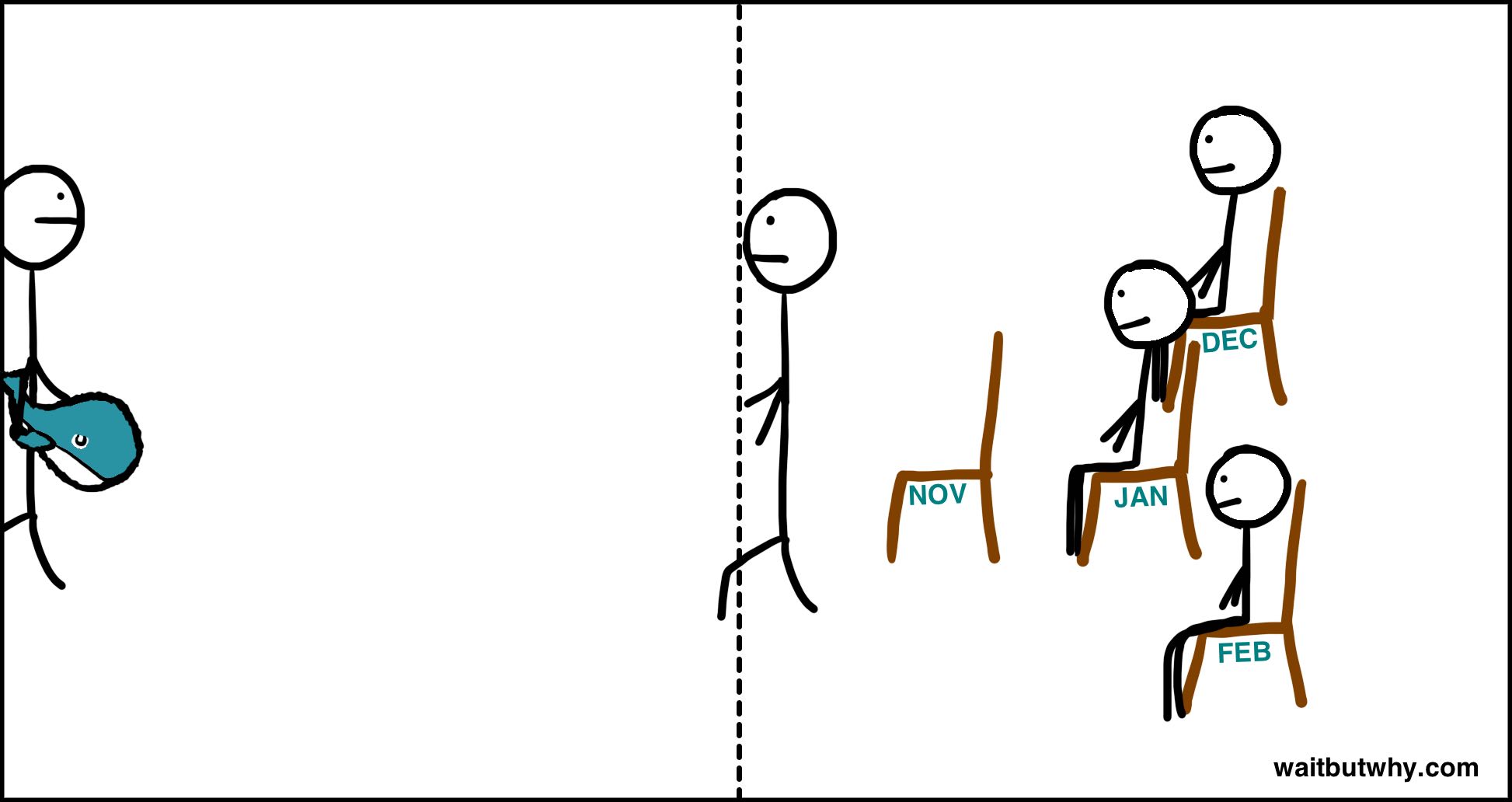

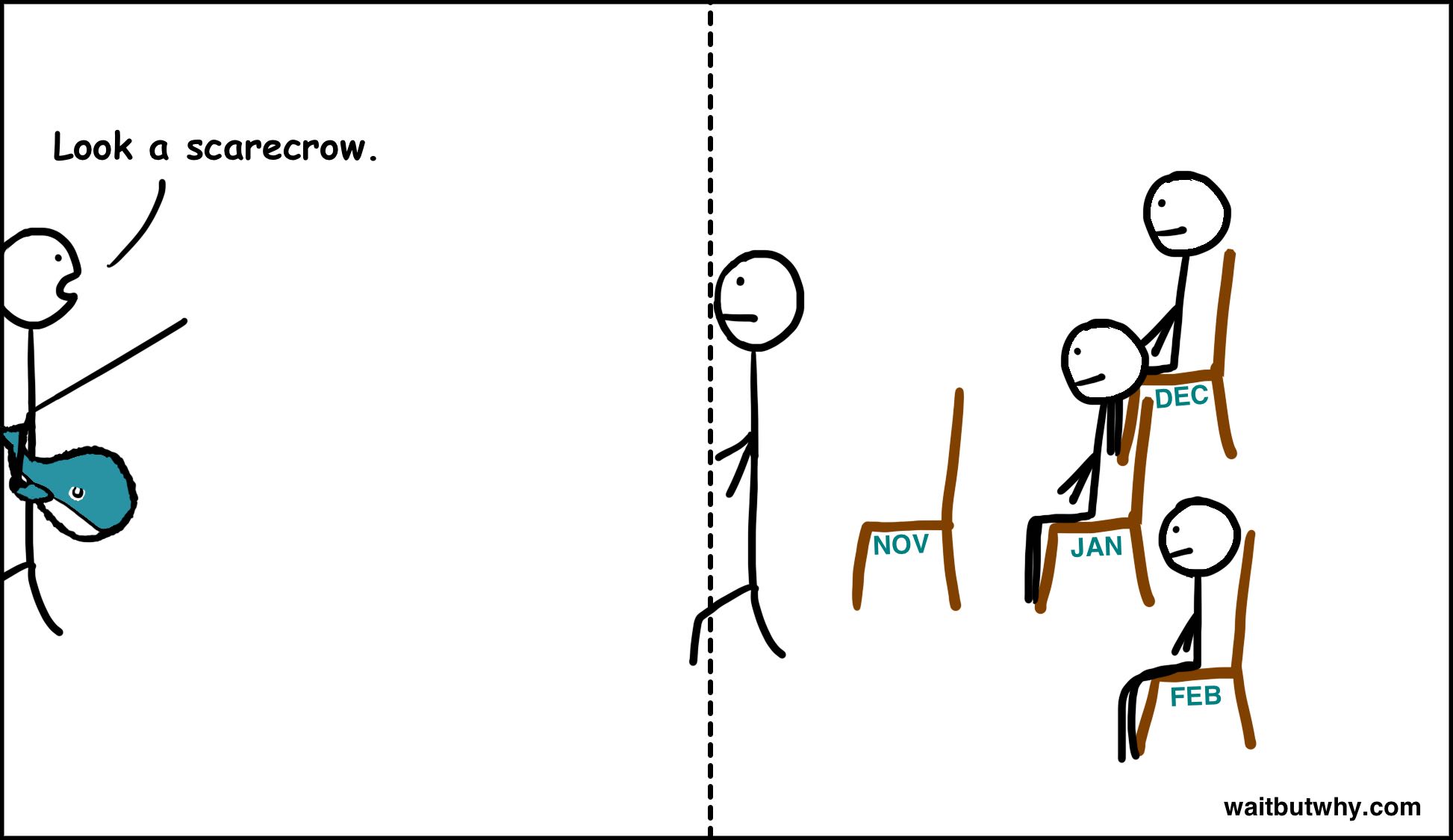

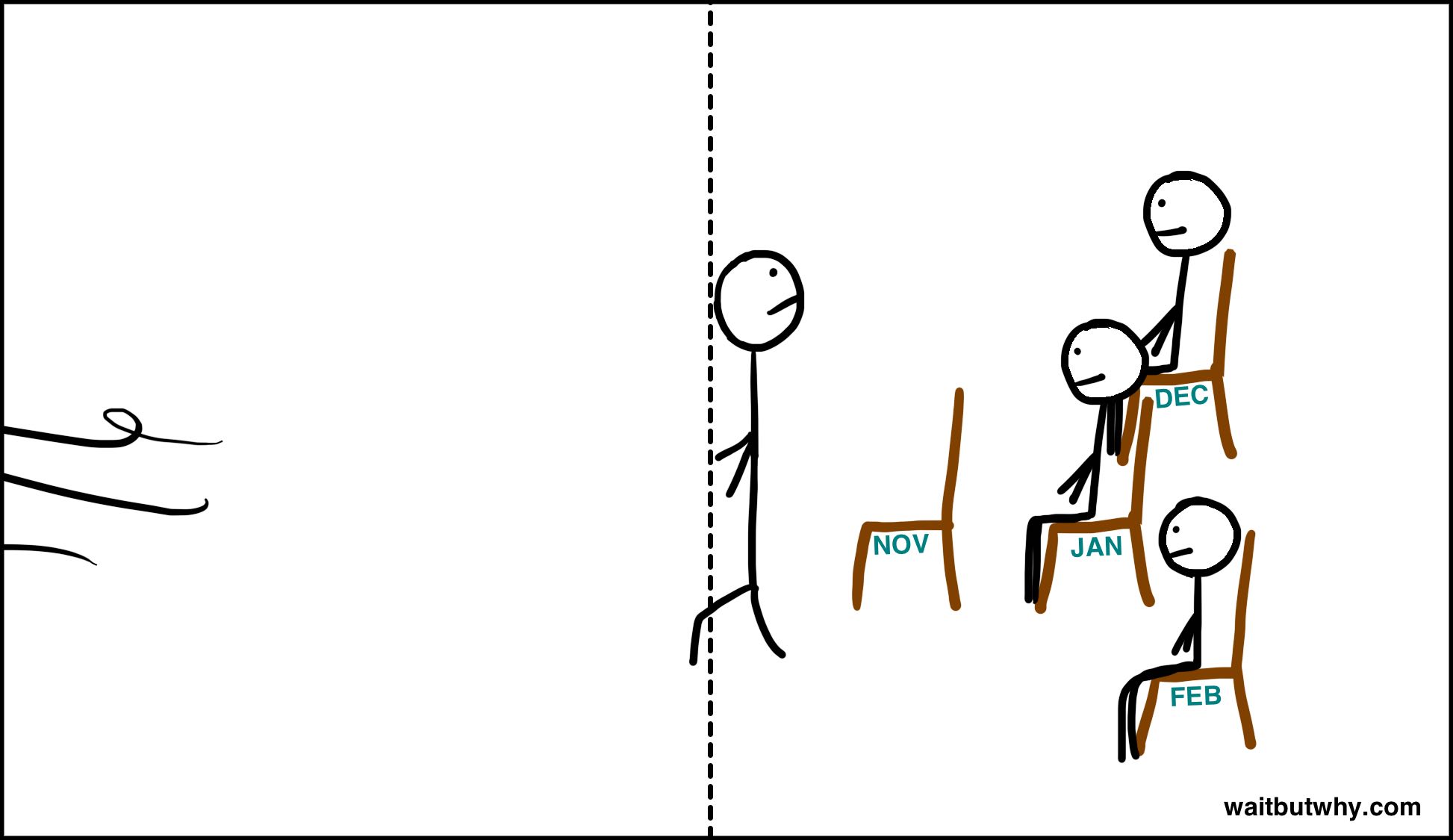

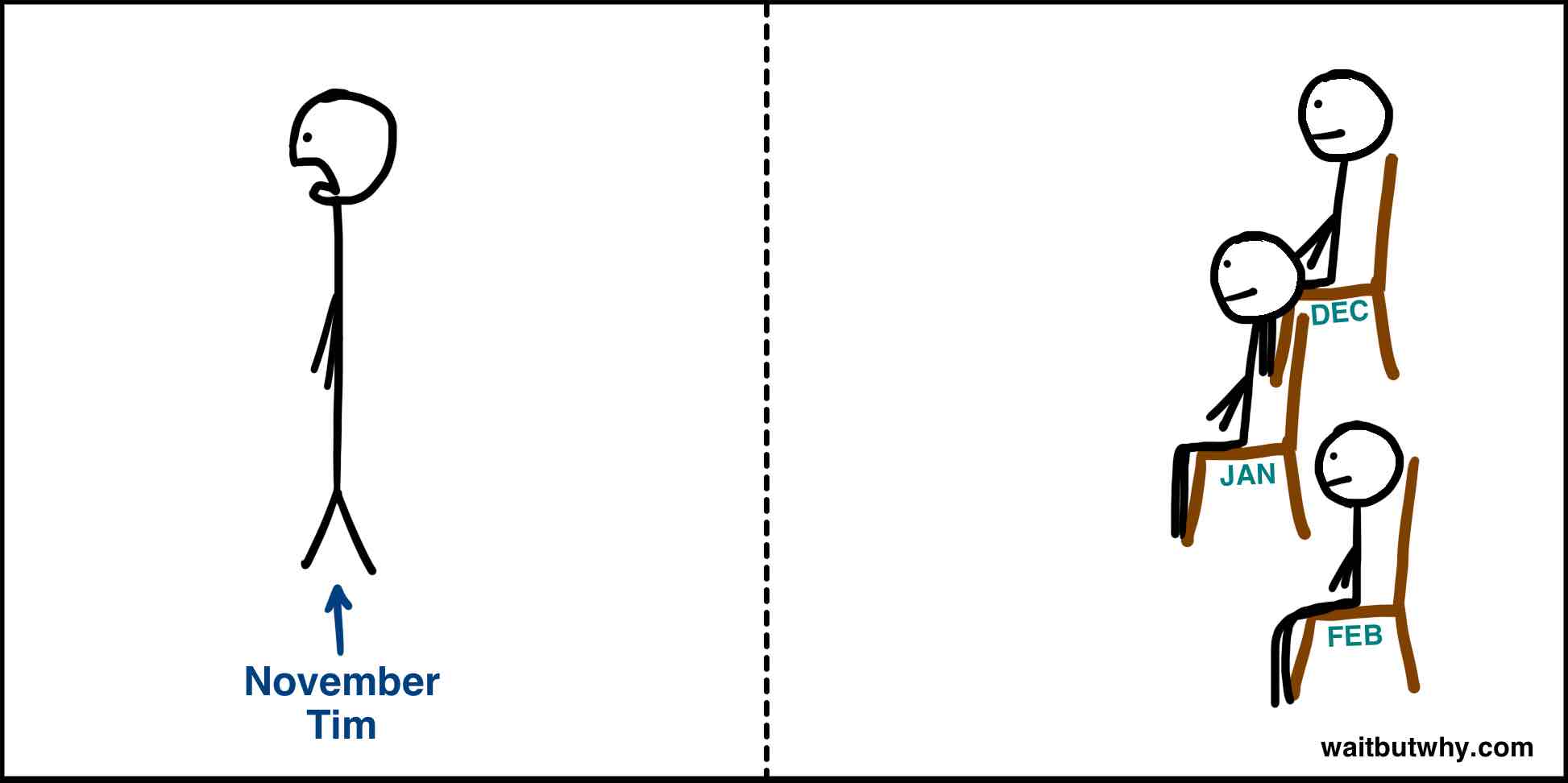

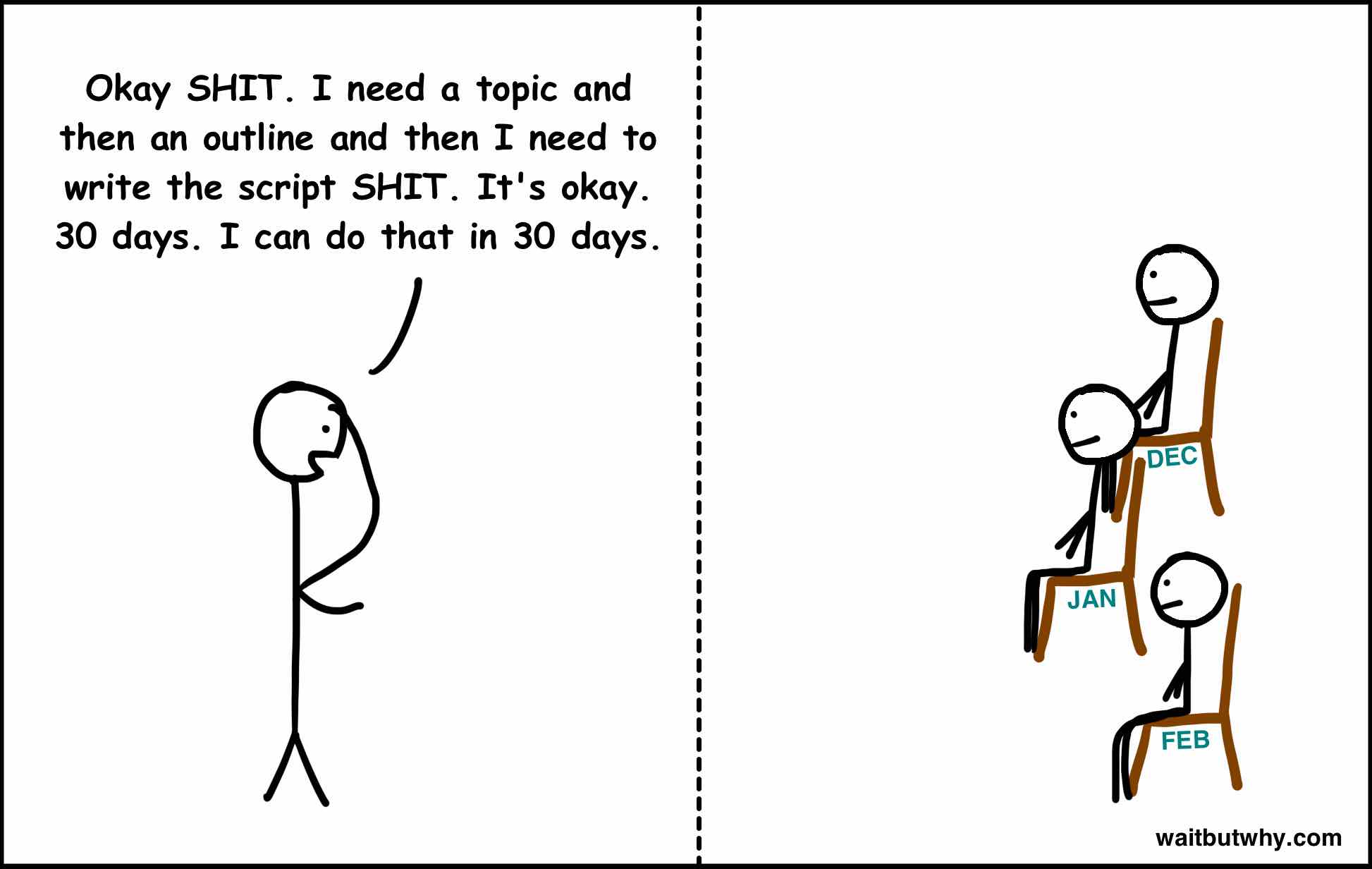

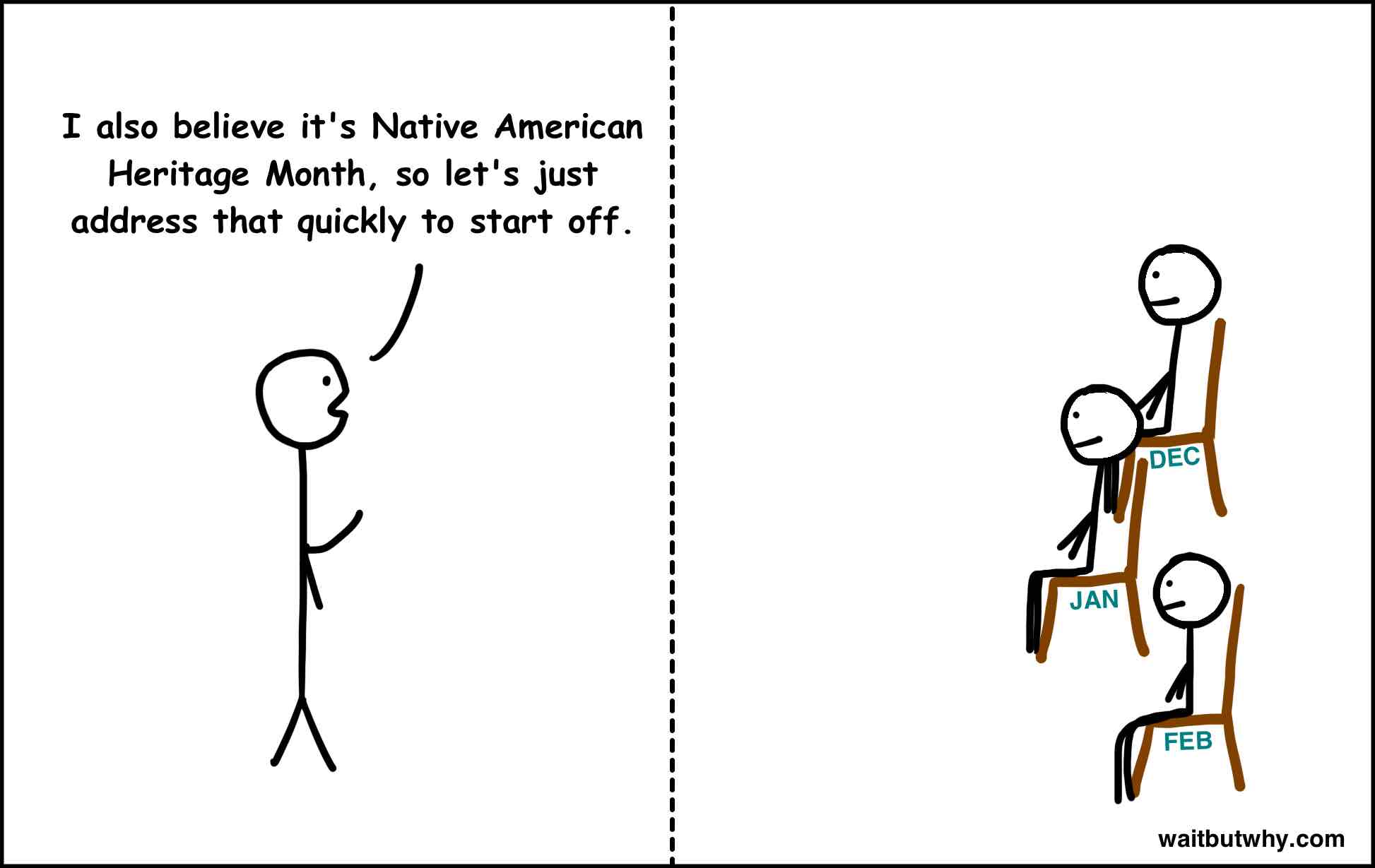

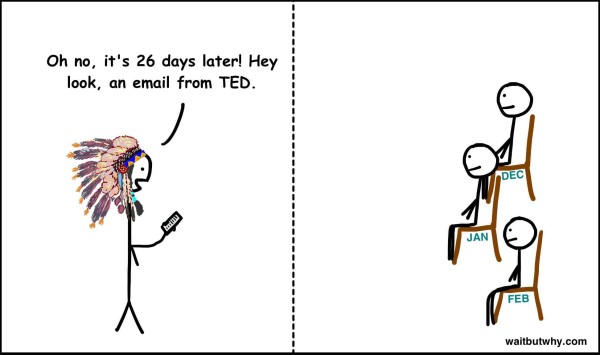

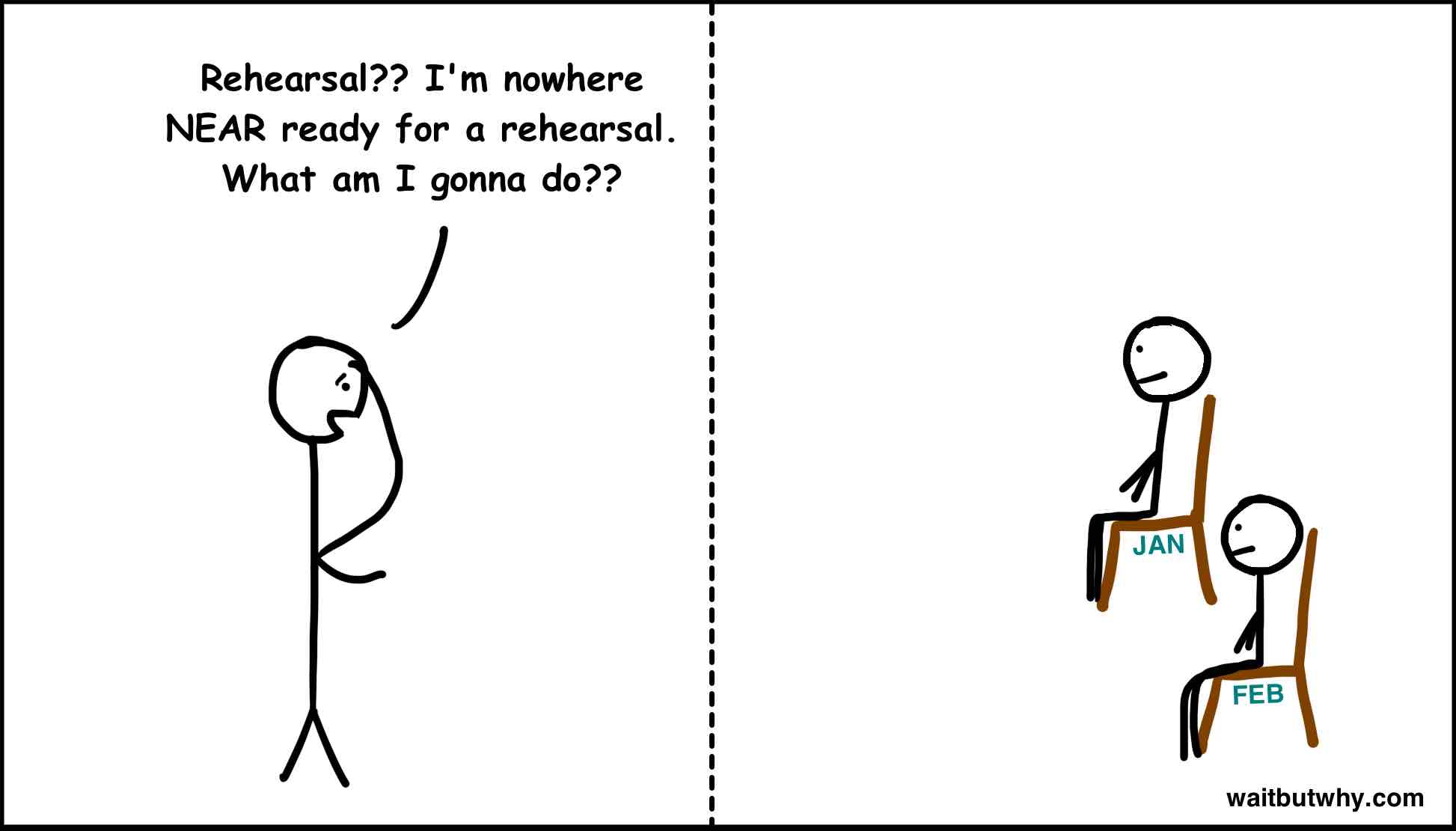

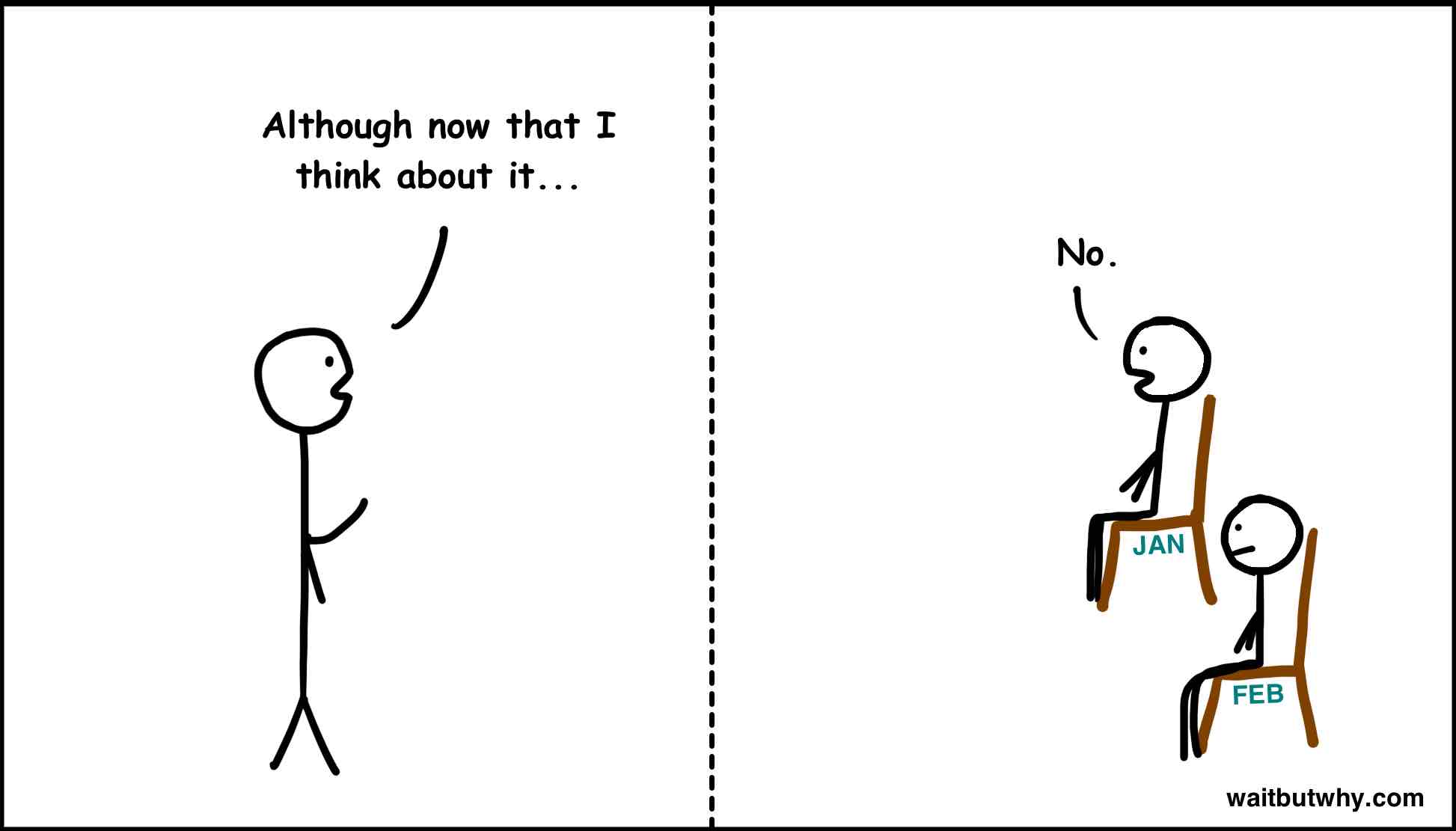

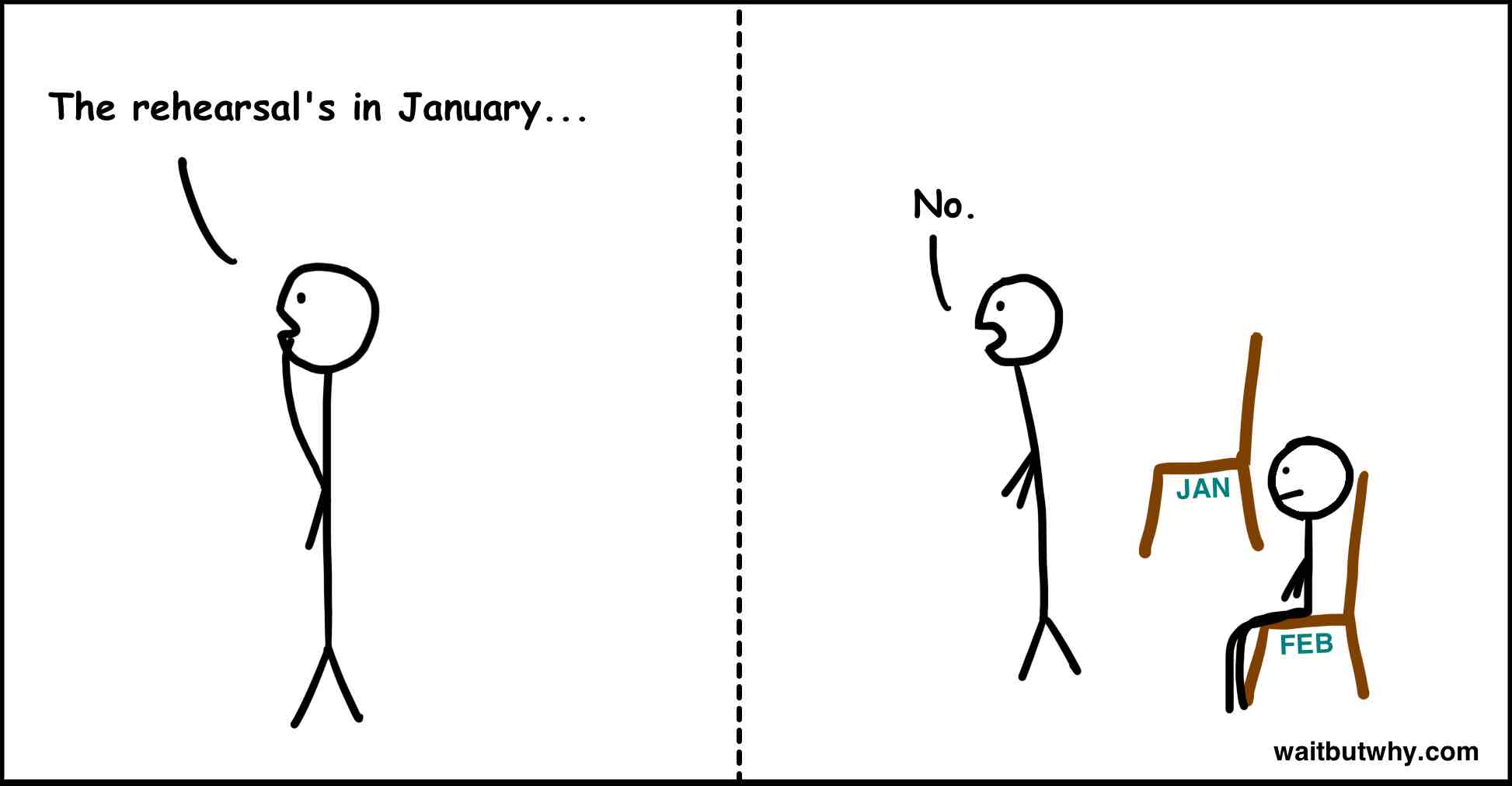

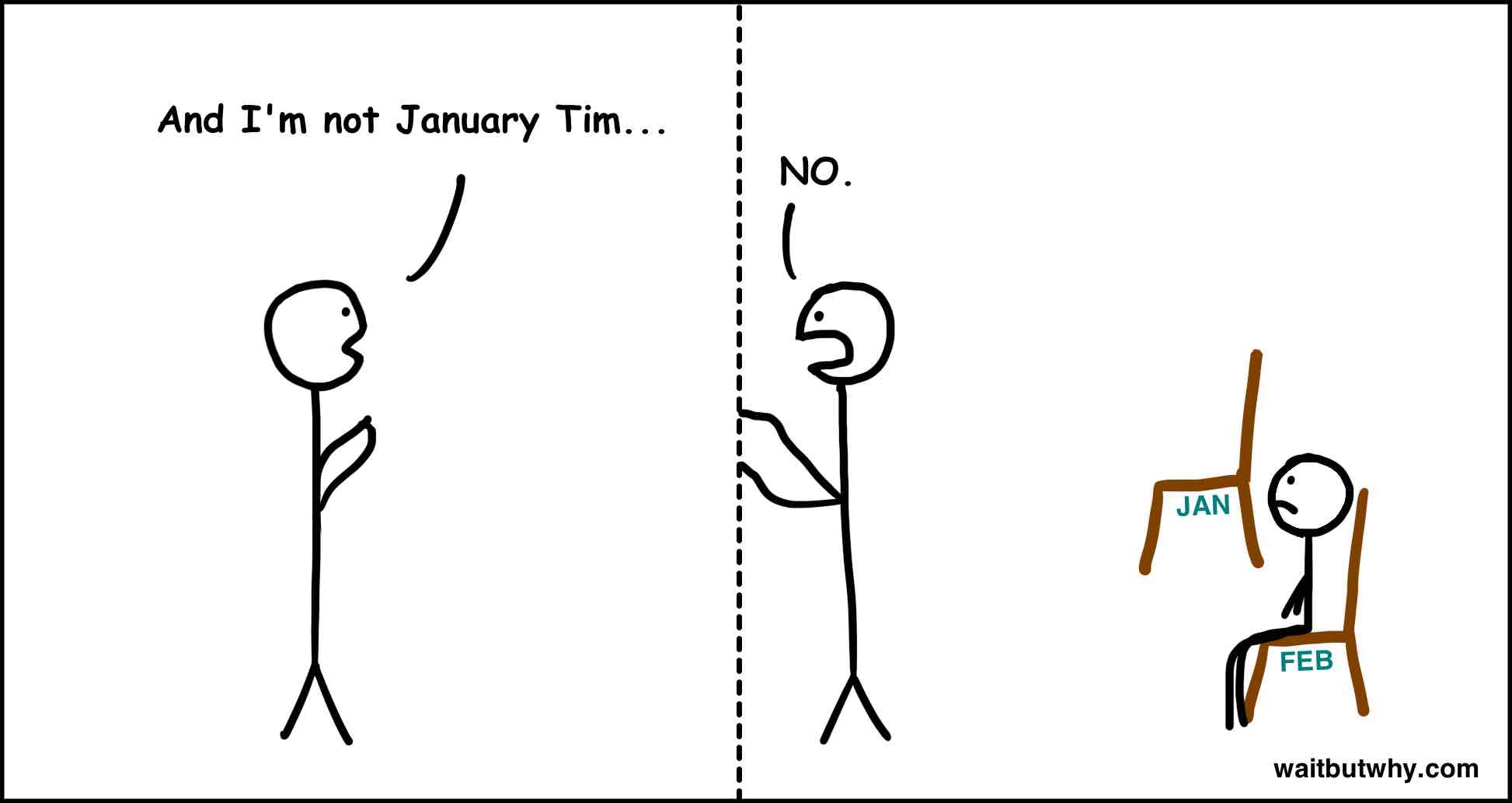

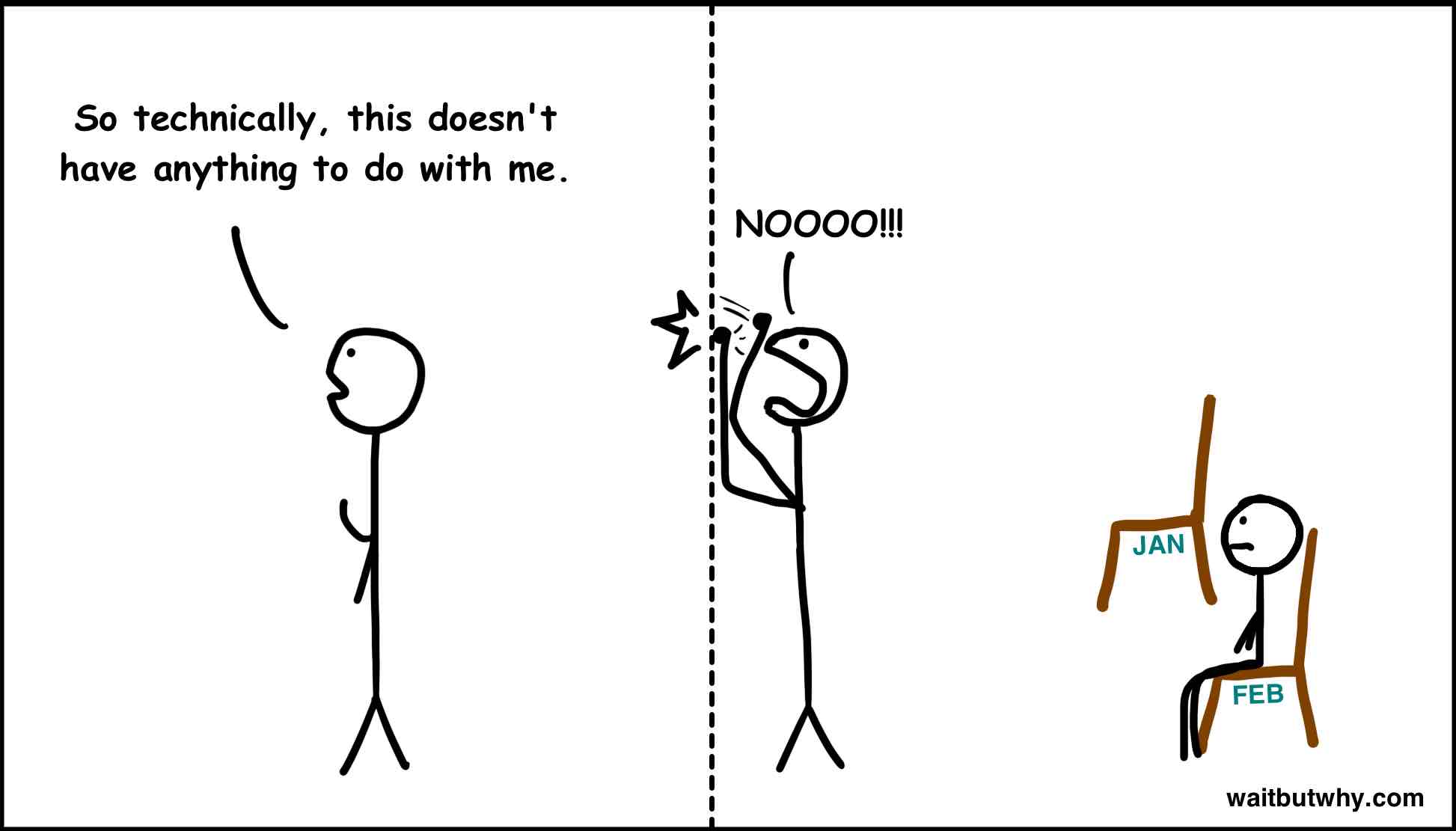

Luckily for August Tim, none of this was his problem. He had an all-star team of employees to carry everything out.

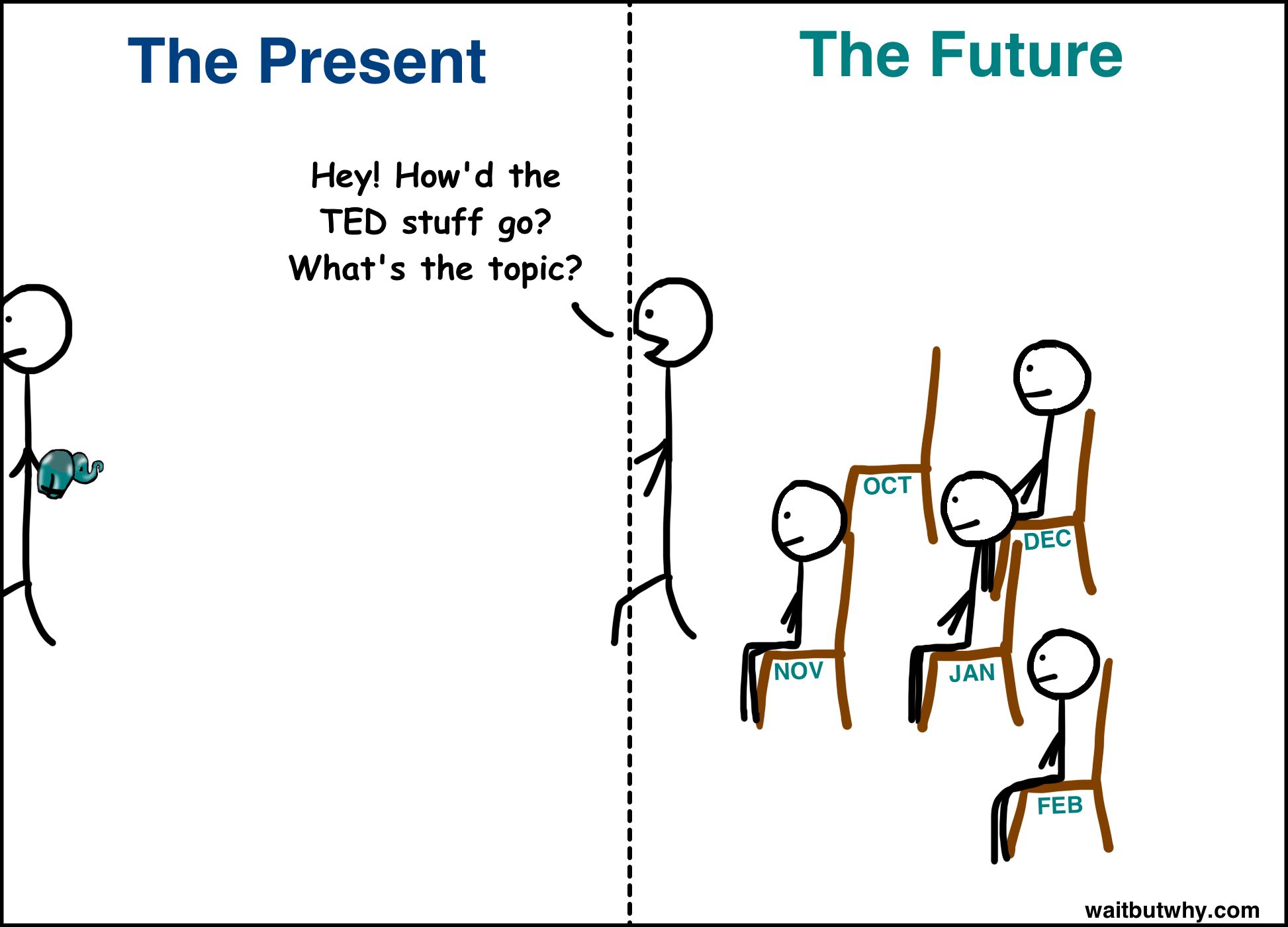

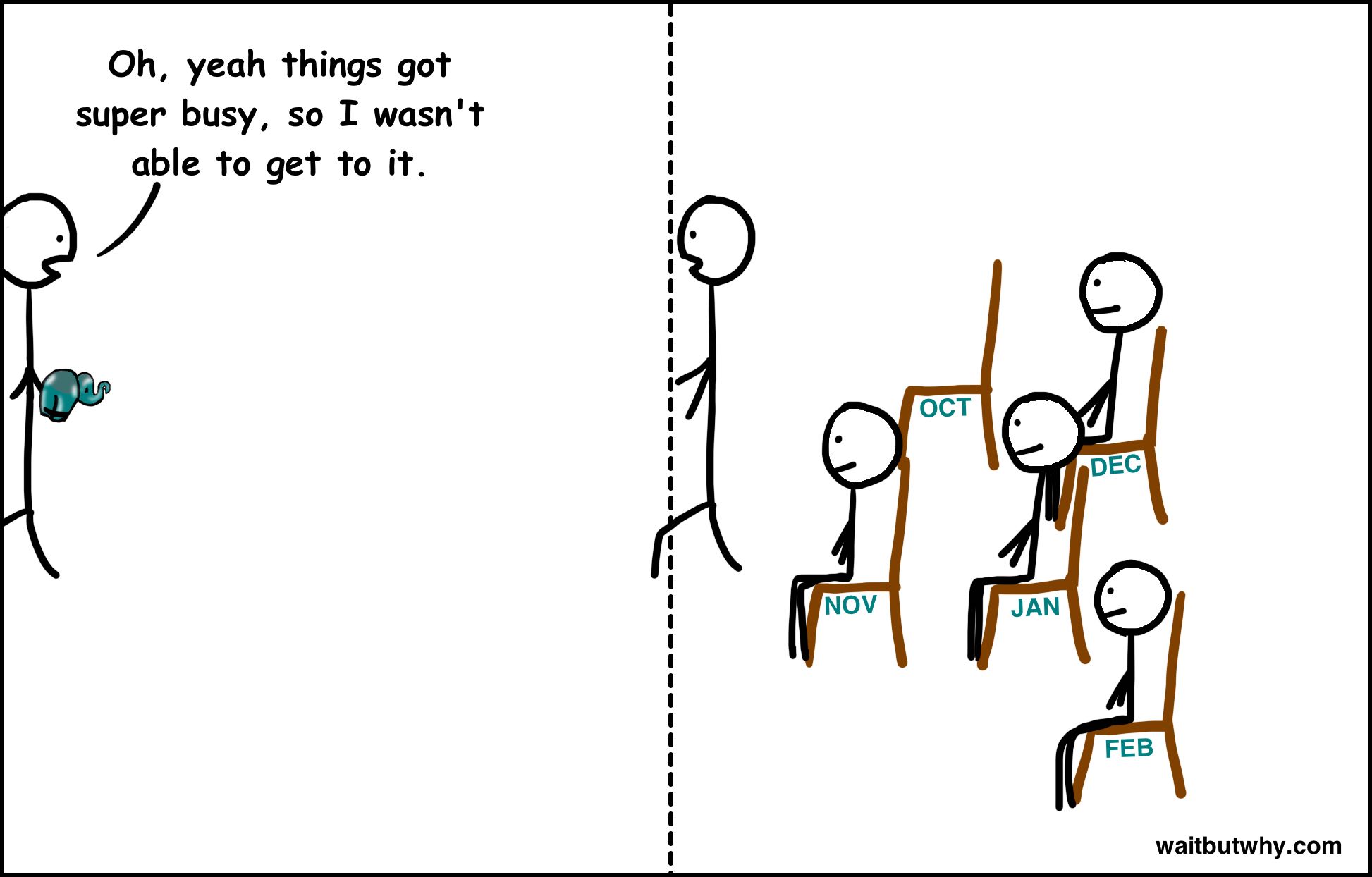

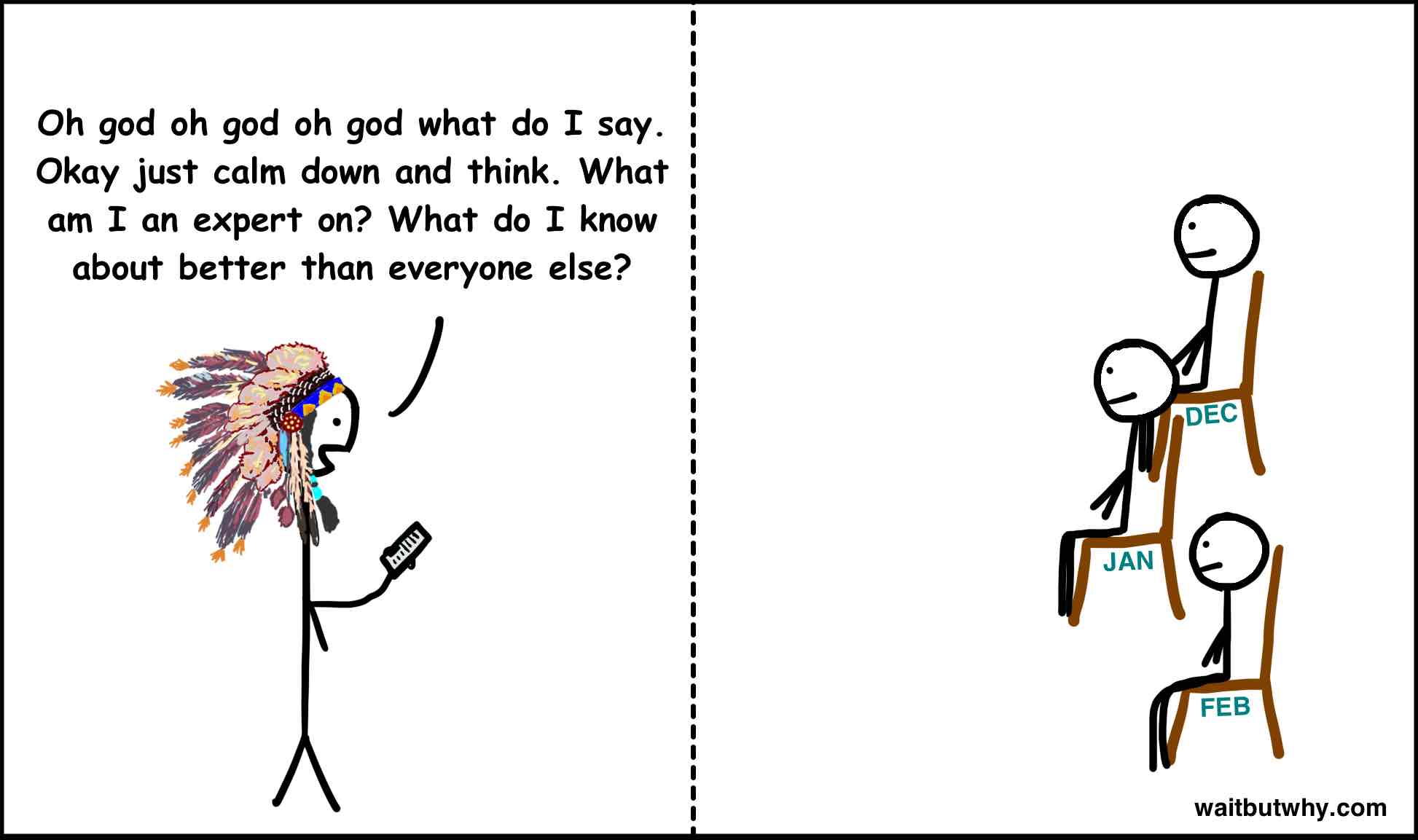

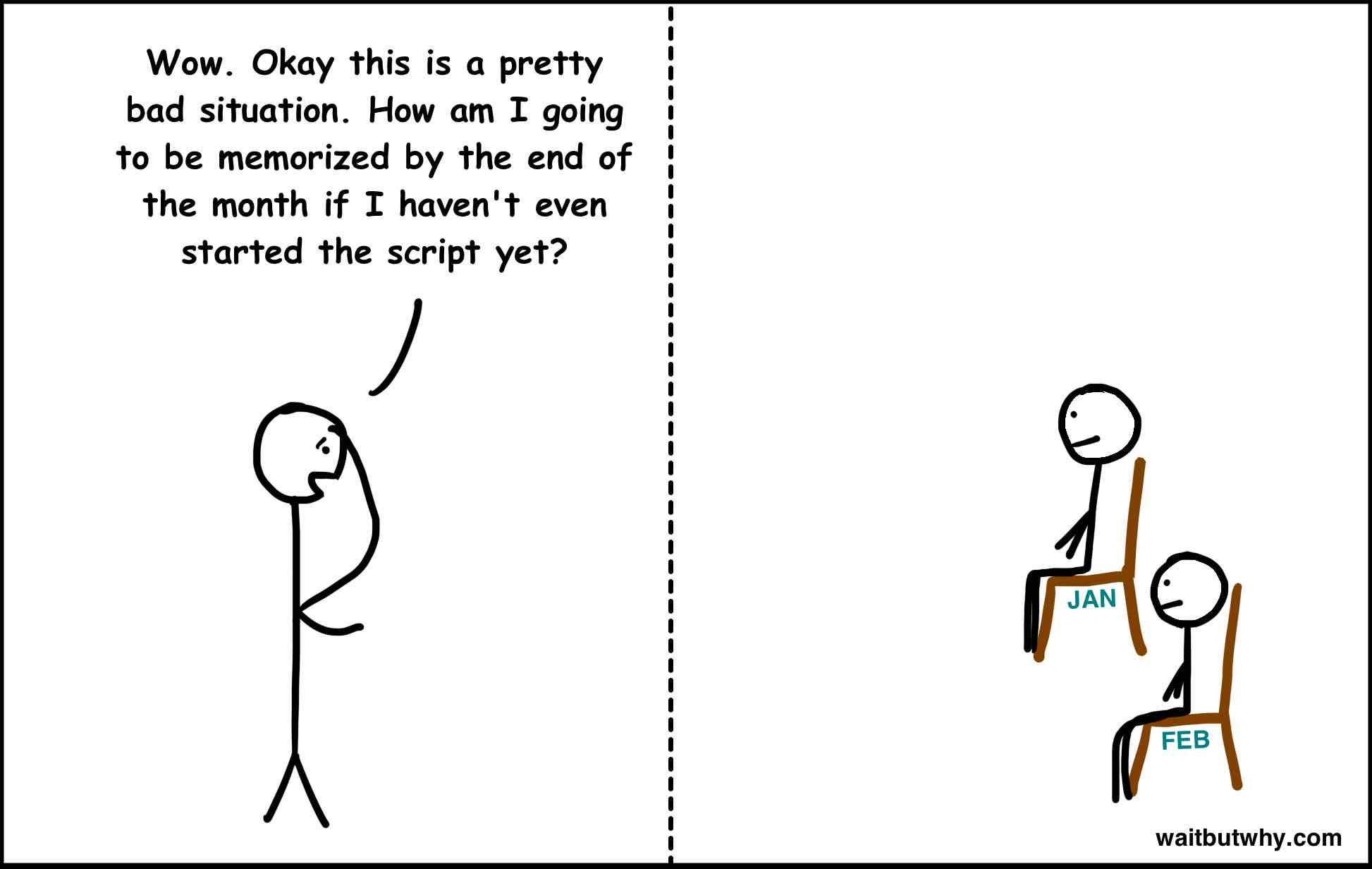

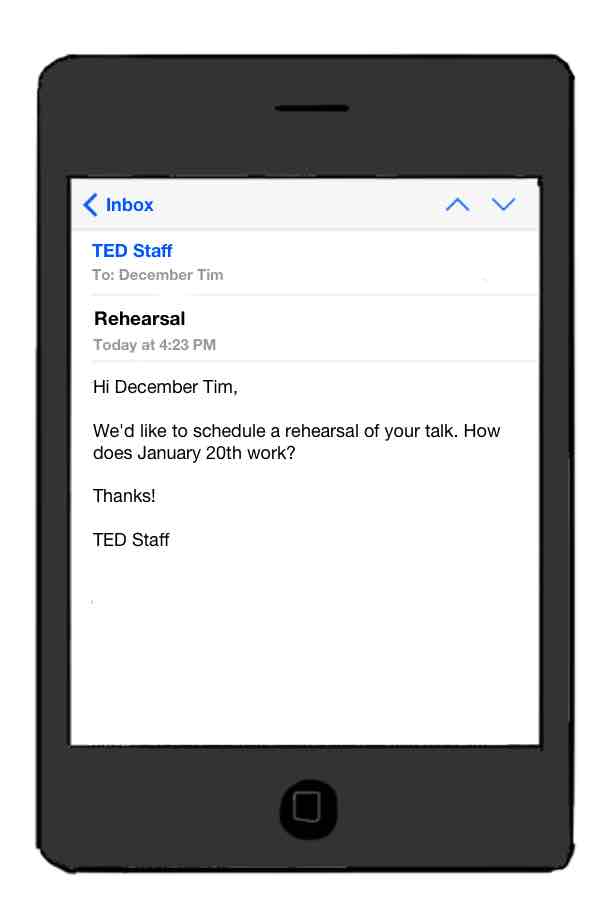

This wasn’t good. With only about a month to go till the talk and a scary rehearsal in front of the TED staff only days away, I was way behind. When it came time for the rehearsal, I had gotten a loose script together, but I wasn’t sure if I liked it.

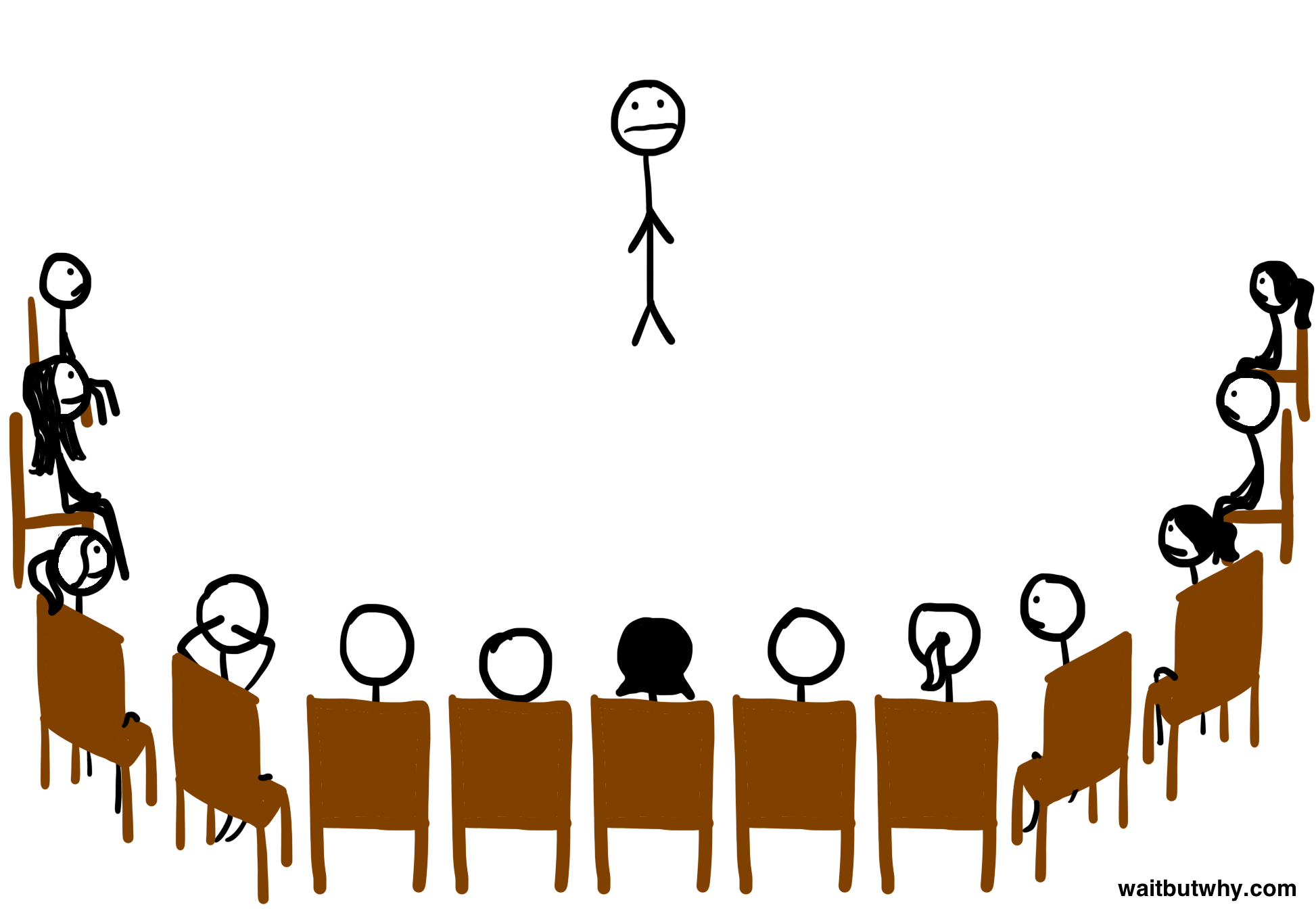

The rehearsal took place in the TED office in New York, in front of a friendly but intimidating semi-circle of TED senior staff.

I went through what I had, and it went okay until the last five minutes of the talk. I really didn’t like that part of the script, and during the rehearsal, I made the impromptu decision to go rogue and improvise, since I hated what was coming out of my mouth. This was a bad idea. What I ended up doing was a rambling and nonsensical ending that wasn’t that different from me picking words out of the dictionary at random and saying them.

There was a lot of work to do.

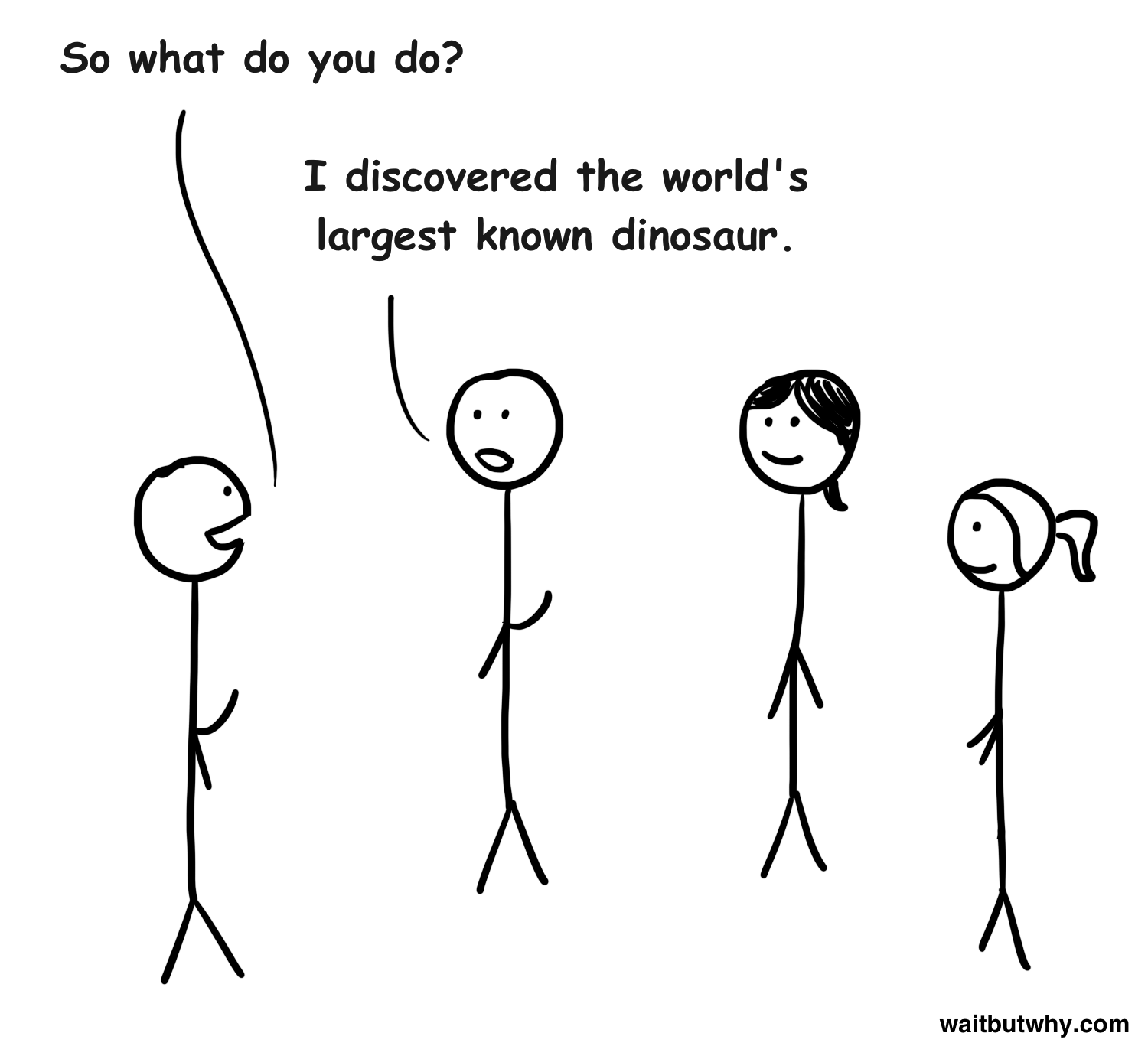

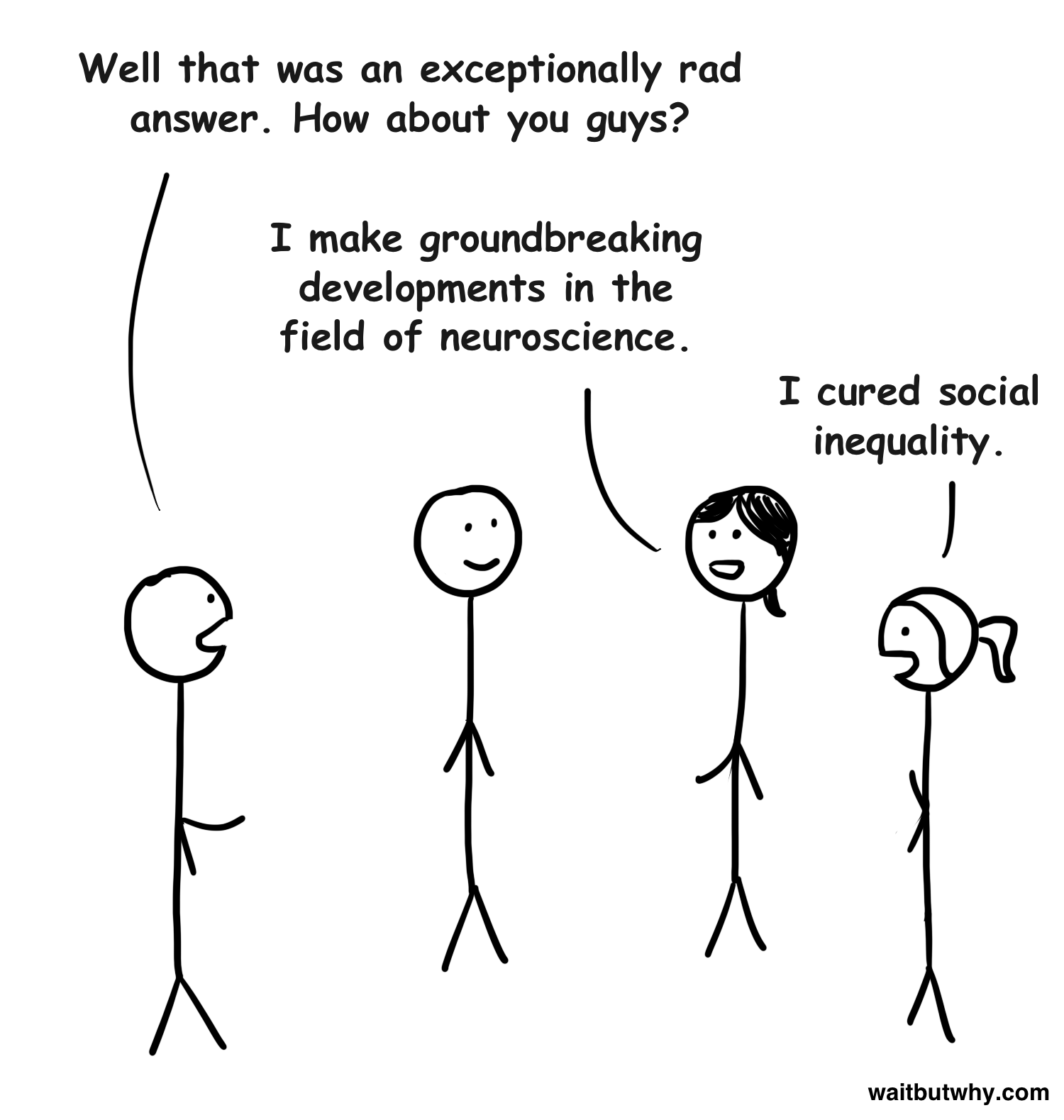

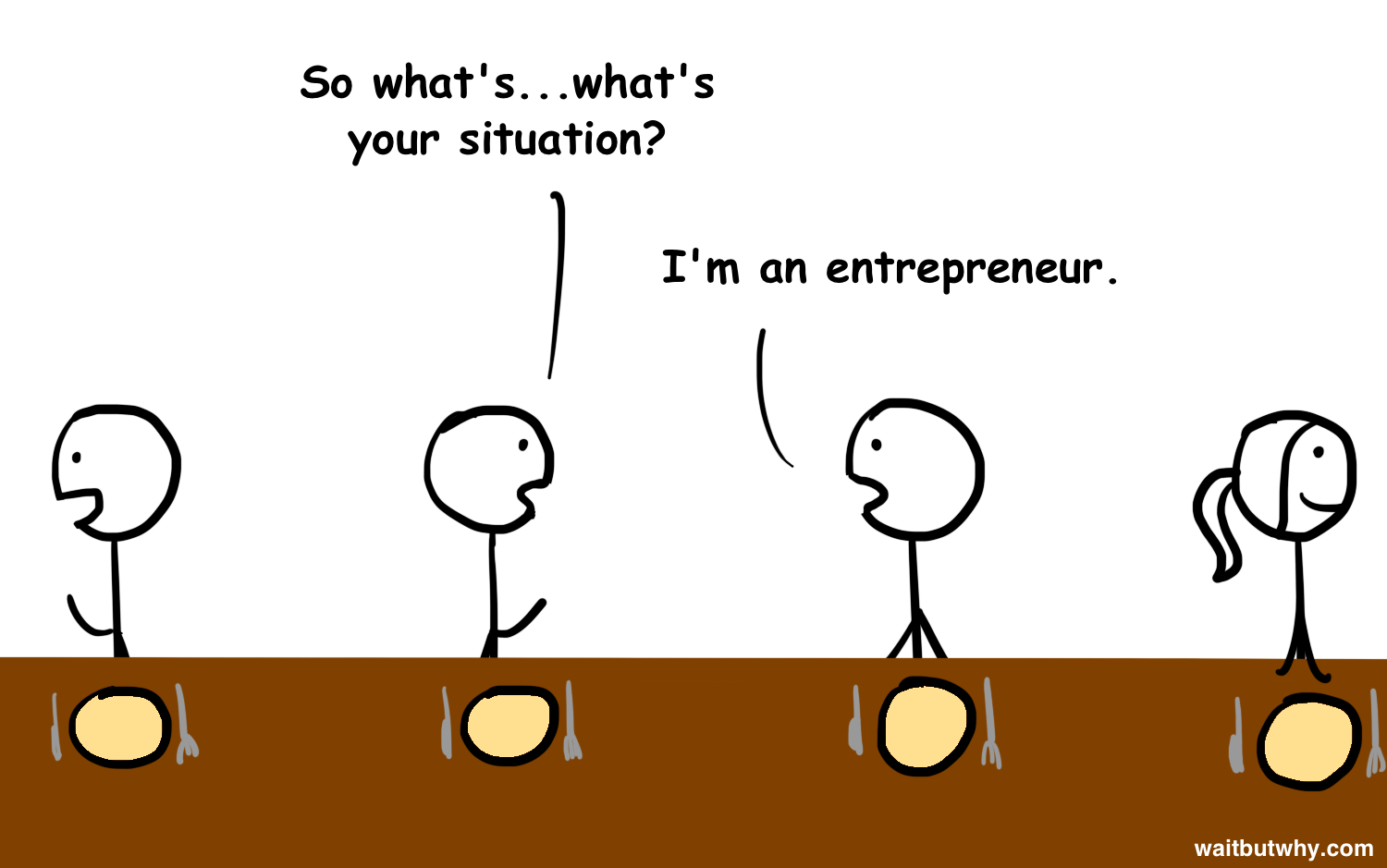

That night, the head of TED, Chris Anderson, hosted a dinner at his New York apartment for the speakers who were in town for rehearsals. If I already felt in over my head in this whole situation, meeting the other speakers didn’t help.

Luckily, I sat down at dinner next to a normal-seeming guy.

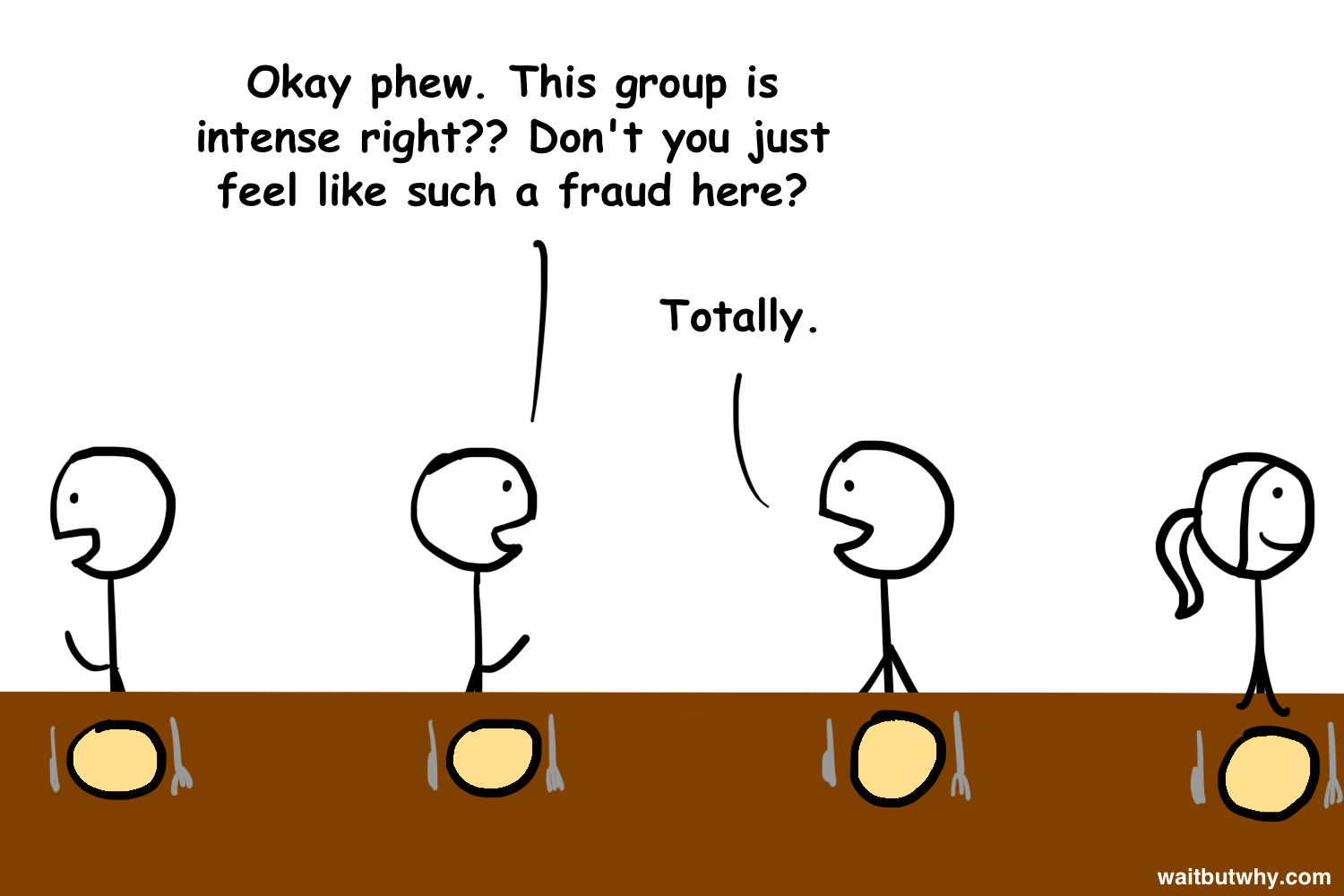

It was a rough start. But the dinner ended up making me feel better. It turns out that even rad people are terrified to do a TED Talk. And by the end, most people had admitted that they felt totally unqualified to be involved in this. Everyone else was going through the same thing I was.

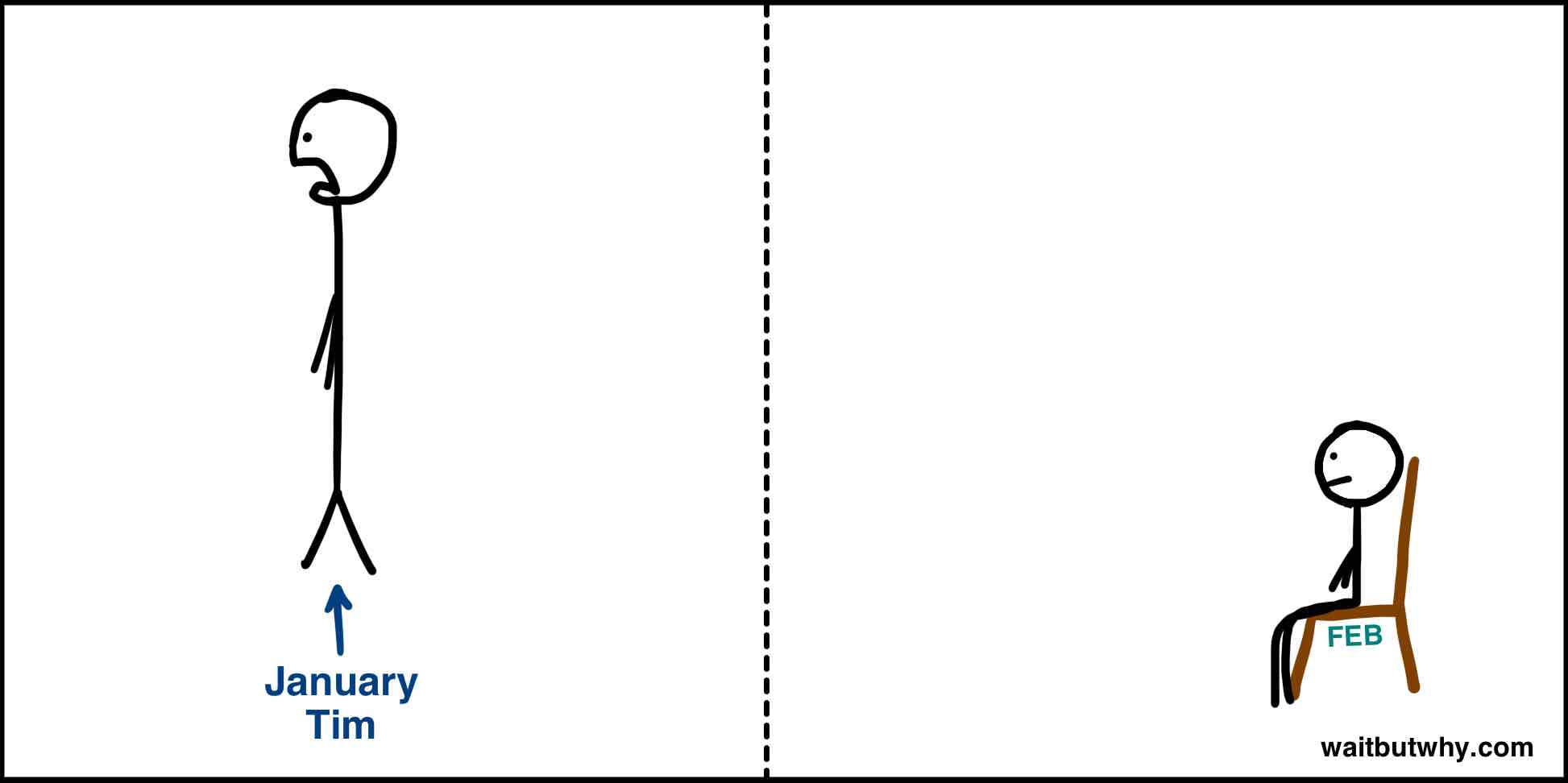

January Tim felt better. So much better that he didn’t do that much for the rest of the month.

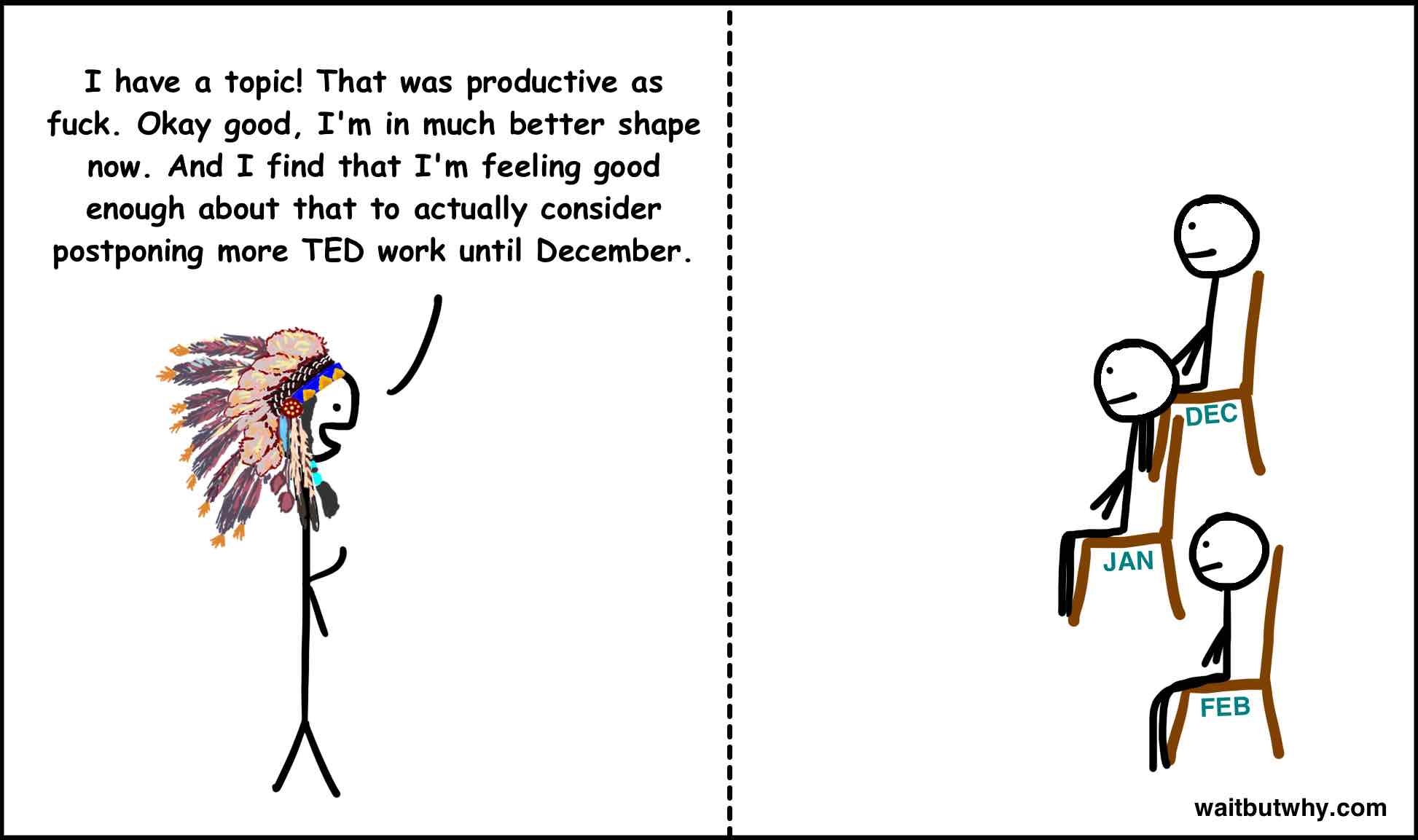

February Tim entered the world furious at every one of his co-workers. But he had no time to be angry—he had to work, every day, all day, immediately. And he did work, a lot, on the first 10 minutes of the talk—the part that was already in pretty good shape. That’s what procrastinators do.

On February 12th, four days before my talk, I flew to Vancouver, still not fully scripted. I got to my hotel and looked out the window, and there it was:

All TED speakers do a fully mic’ed dress rehearsal on the real stage the weekend before the conference starts. Mine was three days before my talk—and it was pretty rough, confirming to me and everyone present that I was officially not a fraud when it came to my topic. The irony of a guy rehearsing his TED Talk about how he’s a bad procrastinator, and being clearly underprepared while doing so, was not lost on anyone.

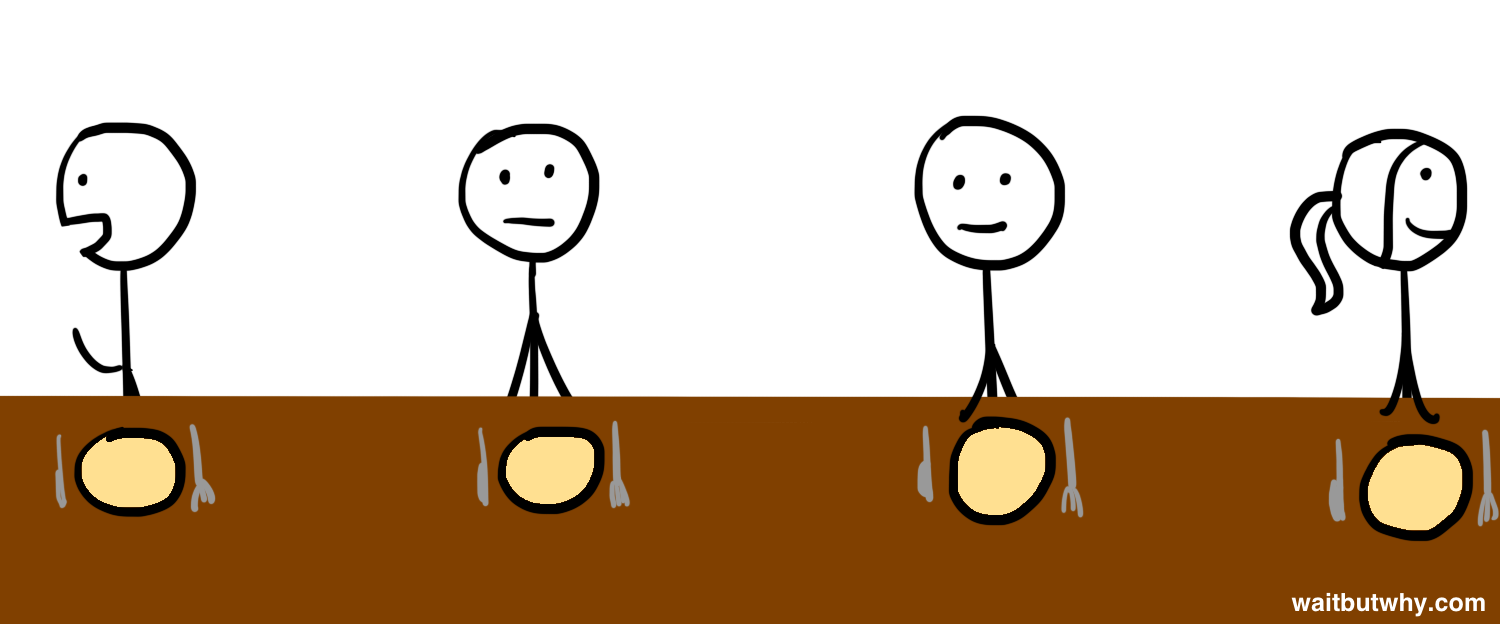

At that point, the first 10 minutes of the talk was here:

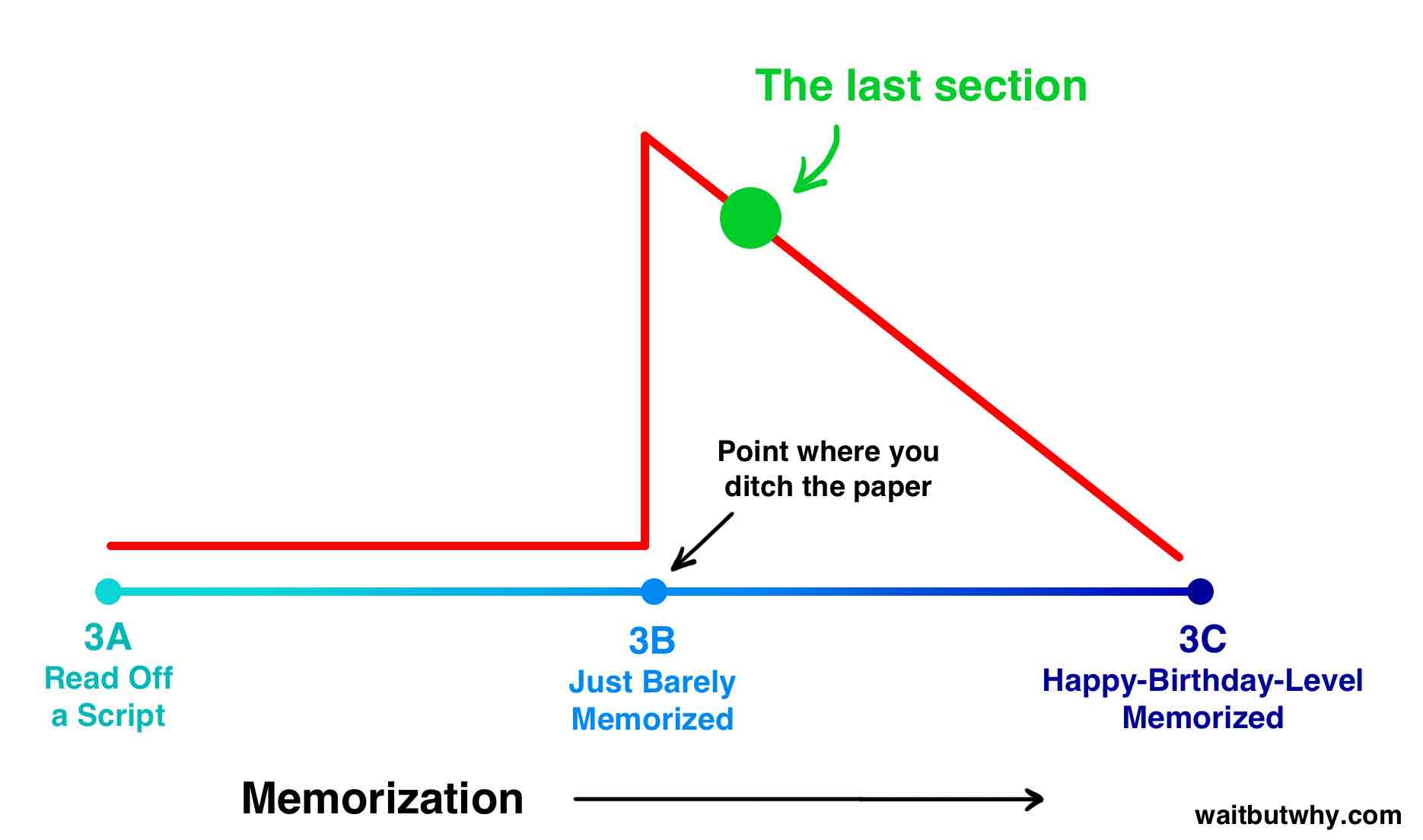

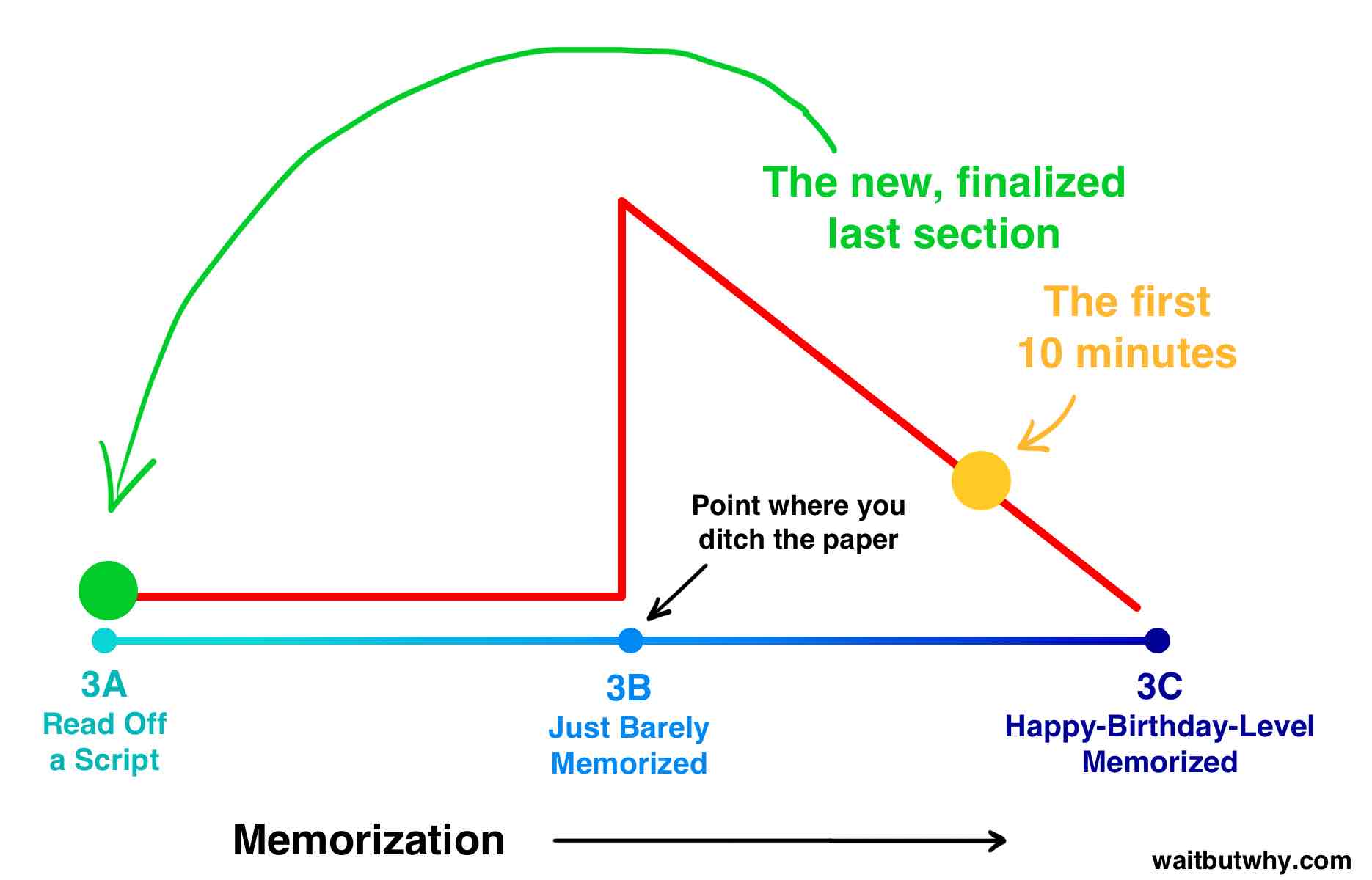

Not ideal, but with a lot of reps over the next three days, it was manageable. The bigger problem is that I still didn’t like the last third of the talk and kept rewriting it. So I’d practice a new ending for a while and get it here—

—only to then rewrite the last section, putting me back here with a whole new thing to memorize:

I fell into a routine of meeting up with fellow speaker and professor/author Adam Grant each night to show him my latest conclusion I hated. He was speaking the same day I was, right after me, but as the author of the book Give and Take, we both knew he had no choice but to be helpful anyway.

On Monday, the day before my talk, the conference began. There were whispers about who was in attendance for the week. Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford. Goldie Hawn and Cher. Tony Hsieh and Travis Kalanick and Chris Sacca and Steve Case and Al Gore. Even Jaden Smith.

Not helpful information.

I spent most of the day in my hotel room, alternating between rewriting the last part of the talk and trying to better memorize the first part. Finally, late that night, I settled on my final script. I liked it. Finally. Only one problem.

Back at 3A with the last part again, this time with only about 16 hours until the talk.

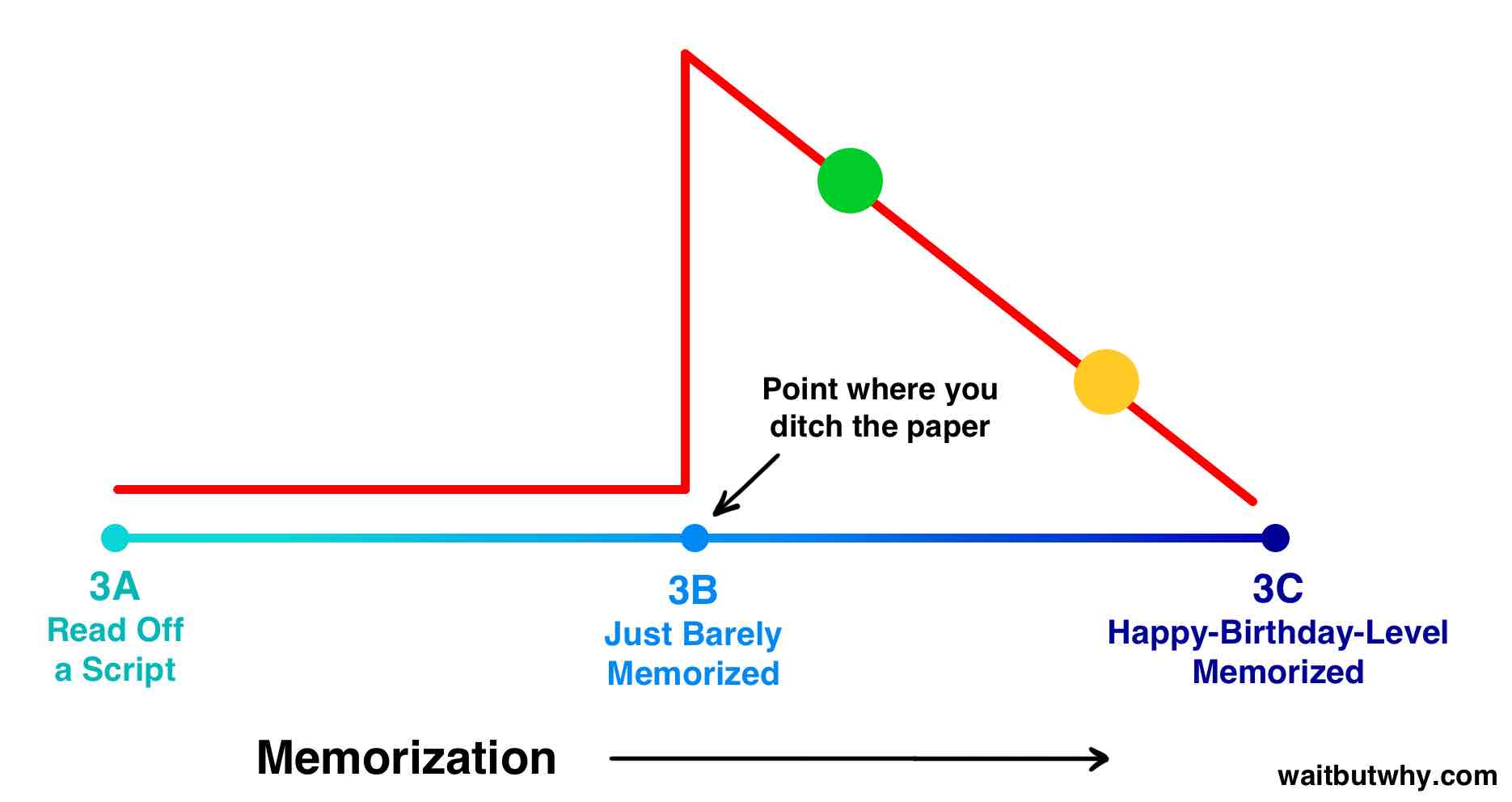

I woke up the morning of my talk, did some jumping jacks in my hotel room like a psycho, and then spent four hours saying the last part over and over, eventually getting things here:

That would have to be good enough—I was out of time. I showed up at the theater the required 90 minutes before my talk for “hair and makeup,” i.e. an upsettingly-friendly lady painting my face with stuff while I engaged in a 10-minute discussion with her about her two cats back at home. Finally free of that, I spent the final hour pacing back and forth and running through the talk in my head, and then, suddenly, I was doing this:

I will say this: The TED stage is a weirdly comforting place. It doesn’t feel like you’re in some huge theater—it feels like you’re on some little red circle surrounded by a bunch of friendly, supportive people who want you to succeed. They designed it that way on purpose, and it works. I was less nervous doing the actual talk than I had been in any of the rehearsals.

And as I made my way through the talk, disaster never struck. I made it through to the end without any major problems.

VICTORY.

When I was done, I sat in a seat they had reserved for me, blacked out, and watched the next series of talks. Immense relief.

The week then turned from what I had openly declared to be the worst week of my life into the best possible shit ever. I never knew much about the TED conference before, but it’s very, very fun. It’s like a little luxury playland where super fancy people come to relax and watch 70 intensely stressed-out, less fancy people get on stage, one by one, and say something interesting. And you know when you’re in a store and there’s some incredibly expensive package of high-end beef jerky or some $9 peanut butter cups by some weeping Brooklyn brand or some pixie bottle of juice that amounts to $6/sip and you don’t buy those things cause who has the nerve to actually live like that? Well all that shit is everywhere on these racks as you walk around TED, and it’s all free. I was chewing for 93% of my waking time the rest of the week.

I’d head into the theater in the morning, some ultra-organic, hyper-cleansing coconut chips in one hand, some wheatgrass extract thing in the other, a thermos full of coffee that took nine minutes for some guy to make using a bunch of test tubes resting in the pocket of the hoodie I wore all week because once your talk is done, literally nothing in the world matters anymore—and I’d plant myself in a seat in the theater and think, “I’m ready, speakers, for you to entertain and educate me. Let’s begin!”

There’s only one stage and only one talk going on at a time, and that talk, in addition to happening live in the theater, is beamed through the entire conference center, which is full of screens and speakers. So sometimes, instead of watching talks in the theater, I’d watch in one of the many cozy simulcast viewing areas—maybe while lying on one of the hundreds of beanbags. Maybe while stretched out on grass under a tree.

Or maybe in a plastic ball pit.

Glorious.

Then it ended and I went home and everything costs money again and I have to do stuff again. Upsetting.

Anyway, that was my TED experience. To all those scared public speakers out there, I’d just say: the fear and dread of public speaking is almost always much worse than the actual experience of doing it. Everyone is just as uncomfortable with it as you are, and if you just put in a good amount of preparation, it almost always ends up going just fine. And then you’ll be really happy you went through all the hell leading up to it. So go for it.

UPDATE: Here’s the talk

______

Public speaking is only one of life’s great perils. Three others to watch out for:

The Great Perils of Social Interaction

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our unannoying-I-promise email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

85% chance that this isn’t a proper usage of a semicolon. But that means there’s a 15% chance that it’s correct! FYI—given my eternal lack of understanding about semicolons, anytime you see me use a semicolon, it means I’m in Wild West mode in that moment and generally feeling very bold.↩

All TED speakers are assigned a time limit by TED, based on what the TED staff thinks is an appropriate time for you and your particular topic. Times range from five or six minutes to 18 minutes. 18 minutes used to be TED’s standard talk length, but in recent years they’ve cut that down to 14 minutes, and now only a few speakers are allowed more than 14. They’re super strict about speakers not going over their assigned time, and there’s a big intimidating countdown screen in the back of the theater that the speaker can see the whole time.↩

“TED’s Chris Anderson” (Departures)↩