If you’re not sure what Odd Things in Odd Places is and why I’m in Greenland, here’s why.

_______________

For the final question on the Odd Things in Odd Places survey, Wait But Why readers had a choice to send me to Norway, Iceland, or Greenland.

Norway didn’t fare very well, which isn’t surprising, since as pleasant and lovely a country as it is, readers didn’t find it an especially hilarious place to send me. But when the final results came in with Iceland and Greenland coming down to a photo finish and Greenland just edging Iceland out for the win, it told me that a lot of readers either didn’t really know what Iceland was or didn’t really know what Greenland was.

So let’s just clear this up now: Iceland is a small, quiet Scandanavian-esque European country with an oddly-intense name; Greenland is a giant ice block in the Arctic where nobody can hear you scream.

That said, I was thrilled with the outcome. Naturally, an entire wall of my bedroom is taken up by a giant world map—and one of my most invigorating life activities is staring up at big, white Greenland and thinking, “What the hell is going on there?“

This thought tends to be followed by a 40-minute Greenland google spiral, so I went into this knowing a few things about the country:1 ←click here

- Just 200 million years ago, the world was Greenland’s oyster. It was the time of Pangaea, when all the continents were cuddling, and Greenland was right in the middle of it all. But then, when everyone got bored and scattered off to separate parts of the globe, Greenland got confused and ended up way up in the Arctic by itself with a shitty internet connection, and that’s where it’s been since then.

- Unsurprisingly, Greenland is a freezing place, ranging from average temperatures in the 30s and 40s F (0 – 10 C) in the summer to pretty constant sub-zero temperatures (-15 to -20 C) all winter.

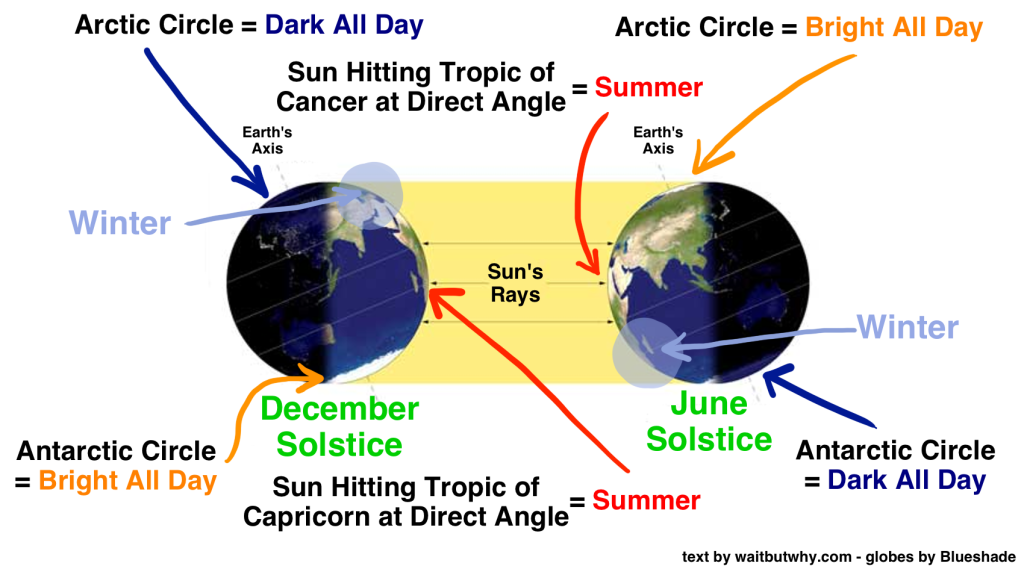

- Way more extreme than the temperature is Greenland’s sunlight situation. Being at such a high latitude, most of the country is dark all winter, even during the day, and light all summer, even at night. In the far north of the country, there are 120 days a year when the sun never sets, 108 days a year when the sun never rises, and only 137 days that include both light and dark.

- While we’re here, quick discussion of the five major latitude lines:

- The Arctic Circle is the lowest latitude in the Northern Hemisphere that experiences at least one winter day with no sunrise and at least one summer day with no sunset. The higher you go above the Arctic Circle, the more of those days there are each year. The Antarctic Circle is the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent situation.

- The Tropic of Cancer is the highest latitude at which the sun is directly overhead at some point throughout the year—in the case of the Tropic of Cancer, that point is the summer solstice around June 21st. The Tropic of Capricorn is the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent, with the sun overhead around December 21st.

- You all know what The Equator is. The sun is directly over the equator on the Spring and Fall Equinoxes in March and September.

Most of Greenland is above the Arctic Circle, which is why its light/dark situation is so extreme.

- Greenland is the largest island in the world (continents don’t count as islands—if they did, everything would be an island), except some archeologists think that Greenland’s ice has weighed down the land so much that if you removed the ice, Greenland would actually be a group of smaller islands now, not one big one.

- Greenland is called Greenland because that’s what famous viking Erik the Red decided to call it when he started the first European settlement there in 982 AD. He went with the name Greenland to make it sound all fuzzy to people back in Europe because in order to start a successful settlement, he needed a lot of settlers willing to migrate there. So the name is a remnant of a 10th century scam.2

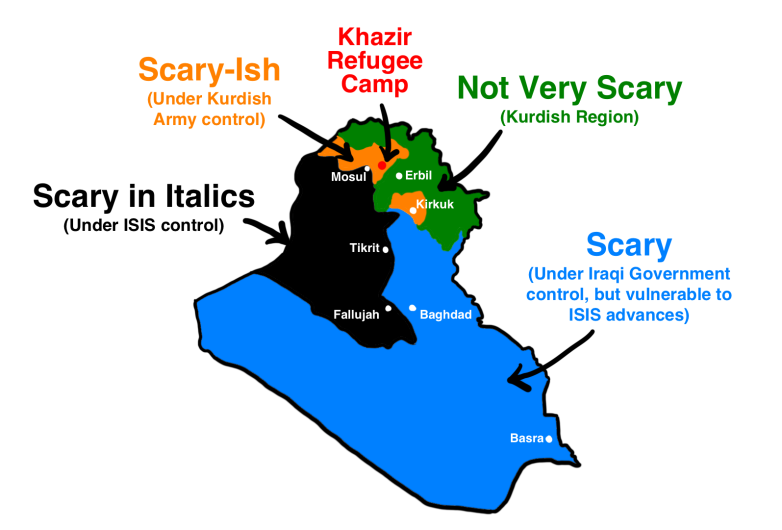

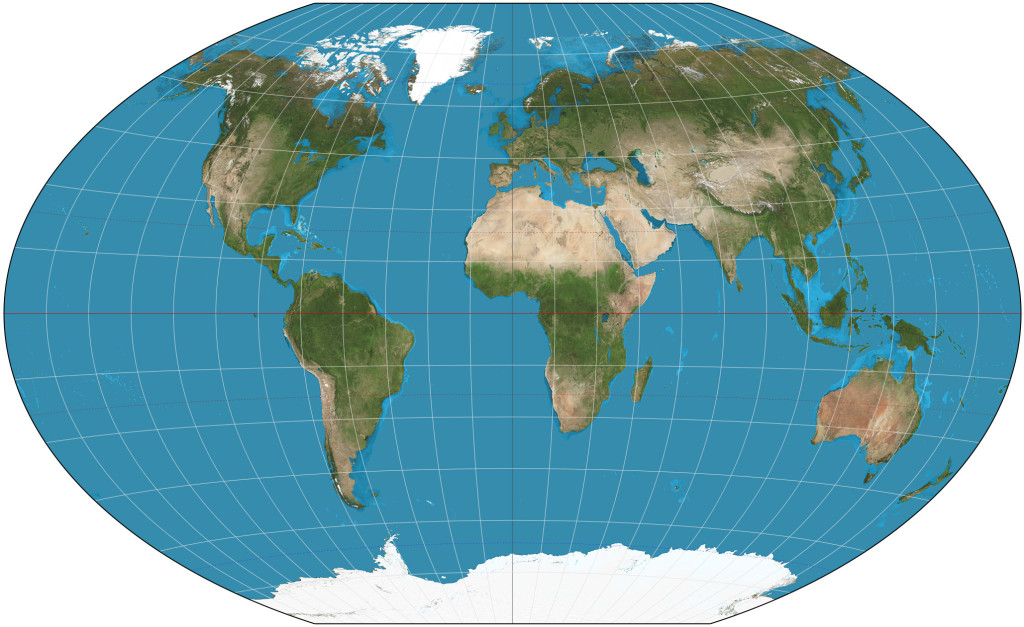

- Given its post-Pangaea predicament, the world decided to throw Greenland a bone and pretend that it’s the size of Africa on maps.

Google Maps

If someone told an alien about a distant planet called Earth and showed him the above map, it would look to him like there was ocean, land, and Greenland, our Overlord.

Some maps are less ridiculous but even they make Greenland far too large:

The reason this happens is twofold: 1) Many maps (like the top one above) are north-centric and vertically stretch the Northern Hemisphere while vertically squishing the Southern Hemisphere by putting the equator below the center, and 2) In order to make a round surface into a flat rectangle, you need to make each latitude line the same length even though on a globe they get much shorter as you move towards the poles—which stretches the highest and lowest latitudes out horizontally (the second map above uses an oval shape to be more accurate, but the poles are still stretched horizontally). Greenland is the most affected by both of these distortions, leaving it looking huge, when an accurate, Arctic-centered globe image shows its actual size to be much smaller, about the size of Saudi Arabia or the Sudans:

And a few weeks ago, it was finally time to stop staring up at the large, mysterious Arctic island that no one talks about and go see what was actually going on there.

I was there for half a month, and here’s what I found:

1) 56,483 People

Of the 7.2 billion humans on today’s Earth, 56,483 of them are living out their lives in Greenland. That’s less than the population of East Village in Manhattan, making Greenland the least densely populated country on Earth (one person for every 15 square miles). Mongolia is the third least dense country on Earth, and it’s 65 times denser than Greenland. Even if you just take the ice-less areas of Greenland around the fringe of the country (that coastal land combines to be about the same as the area of Sweden), Greenland is still by far the least dense country in the world.

So who are these 56,483 people, and how did they end up on Greenland?

For the most part, they’re the Kalaallit, an Inuit people,3 whose ancestors were the Thule people, who migrated out of Asia and over the Bering Strait a few thousand years ago. But the route to Greenland is long, going all the way through Alaska and Northern Canada, and the Thule finally got to Greenland around the same time the Spanish were arriving in the New World, making them no more indigenous to Greenland than European-descended people are to the Americas.

More than 4/5ths of Greenland’s population lives on the southern half of the west coast, and if they want to get from place to place, they do it by snowmobile, dogsled, or if they have a large budget, air or sea. There are no roads connecting towns in Greenland. As for the towns, they’re delicious-looking, with brightly colored houses:

The national language is Greenlandic, but most people speak Danish too, and some speak English. They speak Danish because Denmark established sovereignty over the land in the early 18th century.4 Greenland was granted home rule in 1979 and is running mostly like an independent country these days (I was told the younger generation is especially bored by Denmark and into their own Greenlandic culture).

When it comes to Greenland’s economy, fishing is everything—fish and fish products, especially shrimp, make up 89% of exports.

There are also some dark things going on within the population. According to the World Health Organization, the worldwide suicide rate is 16 per 100,000 people. Country rates range from less than 1 to as high as 31 per 100,000 in Lithuania, the country with the highest rate. The thing is, Greenland isn’t on this list because it’s not an independent country. If it were, it would be the country with by far the highest rate, at 107 suicides per 100,000 people. The government reported that 1 in 5 Greenlanders attempts to kill themselves at some point in their lives, and some I talked to there said almost every Greenlander knows someone who has taken their own life. The logical conclusion would be that suicides spike in the winter when it’s dark almost all the time, but it’s the opposite—the brighter months bring a rise in insomnia, and suicides are more frequent then.

There’s also a large problem with alcoholism in the country, which may be connected to the suicide rate, or they could both be symptoms of something else—one theory blames rapid modernization in what until recently has been a very traditional culture.

In my limited time there, I found the people to be overall very kind, but also quite shy and somewhat wary of foreigners, which made it harder here than other places this summer to get to know locals beyond a surface level.

2) A 2,565,000,000,000,000 Tonne Ice Cube

Ice ages happen when a subtle shift in the Earth’s orbit make world temperatures just a bit cooler. It doesn’t have to be a huge change, but over time, it turns into an ice age, whereby huge ice sheets build up around the poles and then expand outward toward the equator, wreaking havoc while doing so—Long Island and Cape Cod are just shredded bits of land from the sweep of the huge North American ice sheet in the last glacial period, and the Great Lakes are just divots torn out of the Earth by the ice sheet and filled with meltwater as the ice sheet retreated.

These huge sheets don’t form and expand because there is more snow falling, but because the small changes in temperature mean that less of the snow melts each year and a slow buildup occurs. The white snow then reflects more of the sun’s rays, allowing the ground to absorb less of it, which exacerbates the effect. Layer after layer of snow builds up until it turns into rock solid ice under its own weight, and that’s how an ice sheet forms.

Ice ages are millions of years long, and they consist of alternating cold periods called glacials (which typically last 40,000 – 100,000 years) and short, temperate periods called interglacials (which last around 10,000 years). Think of interglacials as a time out from the ice age before it gets going on the next glacial. When you hear about the last ice age 10,000 years ago, you’re actually hearing about the last glacial in the ice age we’re currently in. We just don’t realize we’re smack in the middle of an ice age because we, and all of recorded human history, has taken place within one of those little interglacial timeouts. That’s why there are currently ice sheets in the Arctic and Antarctic, as well as glaciers in many other parts of the Earth, even temperate places like New Zealand—because we’re in an ice age. When there’s no ice age going on, there aren’t any ice sheets, anywhere (which has been the case for 85% of Earth’s history).

There have been 17 glacial/interglacial pairs so far in this ice age and scientists predict as many as 50 more, each pair lasting as long as 100,000 years, before the Earth is out of this ice age. And this interglacial we’re in has been unusually long already—it seems we’re due for the next glacial to start.

When it comes to global warming, while in the long run, two factors are well beyond human effects—the oncoming next glacial, which will cool our asses down whether we like it or not, and the eventual ending of this grand ice age, which will melt all the polar and Antarctic ice and raise ocean levels, no matter what we do—the geological clock moves so slowly that those things happen over thousands or millions of years, while the effects of global warming that terrify scientists can be disastrous for humans in the next few hundred years before any of these larger forces have moved much.

Back to Greenland. So as a result of that “more snow falling than melting” buildup phenomenon, Greenland now has what I enjoy calling a 2,565,000,000,000,000 tonne ice cube sitting on top of it. Some facts about this ice cube:

- No, it’s not a cube, it’s an ice sheet

- It weighs 2.565 quadrillion tonnes, which is equal to the weight of 7.5 billion Empire State Buildings

- Its mean height/thickness is over 2km, and over 3km at its thickest point. Picture 10 skyscrapers stacked on top of each other—they would still be under the ice. That’s how thick it is.

- If the whole thing were to melt, it would raise global sea levels by 23 feet and flood almost every coastal city

- Now take everything I just said and multiply it by ten and you have the Antarctic ice sheet

- Together, the two ice sheets contain more than 99% of the freshwater ice on Earth, and over 2/3 of the world’s fresh water5

I went to the edge of where the dry coastal land ends and the ice sheet begins one day. Here’s what it looks like:

Because of the weight of Greenland’s ice sheet, it has forced the interior of the island to sink down a bit, making Greenland kind of like a bowl, lined with mountains. Eventually, as more and more ice builds up, some inevitably “spills” out over the edge of the bowl. That’s what a glacier is. Elephant Foot Glacier in northeast Greenland is a perfect spillage example:

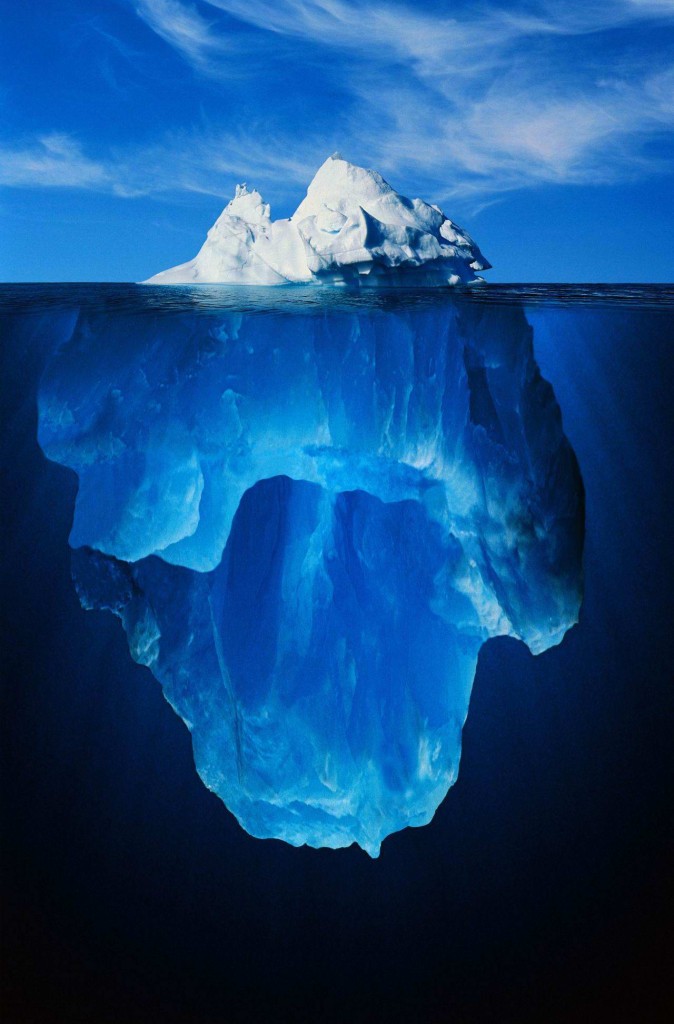

And as a glacier eventually gets to the ocean, pieces of it break off into the water—that’s where icebergs come from. Greenland glaciers calve off 12,000 – 15,000 icebergs a year.

The most active glacier in the Northern Hemisphere is near the town of Ilulissat, halfway up the west coast, where a huge glacier is spilling into the ocean at the mouth of a narrow fjord, filling the fjord with giant icebergs. Here’s the fjord, and that mountain through the fog isn’t a mountain—it’s a massive iceberg:

When you look at those icebergs, think about a drink with ice cubes in it. You know how most of a floating ice cube is beneath the surface with just a small corner of the cube poking out? That’s happening with these icebergs too—what you see above the surface is approximately 1/8th of the whole iceberg—

This fact kept blowing my mind. Like check out this photo of the part of the fjord where it meets the wider ocean:

I was told that the huge iceberg in the back is the height of a 40-story building—above water. That means the part below water extends down about 3,200 feet—farther down than the Burj Khalifa.

And that’s nothing. An iceberg bigger than Manhattan broke off the glacier and moved down the same fjord in May.6

In 1909, an iceberg broke off the same glacier in those pictures and spent three years making its way down the ice fjord and through the North Atlantic Ocean, where it sunk the Titanic in 1912:

3) 21,000 Wolves

They’re everywhere. And they’re not actually wolves, they’re an ancient breed of wolf-like dogs descended from dogs brought to Greenland by the first Inuit settlers. But they look like wolves, they howl like wolves, and when I’d be walking down a road, thinking life was normal, and then look to my left and see 40 of them right there, chained up, each staring intently at me as I walked by, they scared the shit out of me like wolves.7

The dogs are there, of course, for sledding purposes. With no long-distance roads, dog sledding is a key mode of transportation, as well as a competitive sport. I didn’t get a chance to try it because it was the summer, but I asked a lot of questions—apparently you don’t just sit there on your sled hanging out while the dogs take you on a fun ride, like I had pictured. You’re on skis, completely focused, working strenuously the whole time. And it can be dangerous—if you’re somewhere remote on the ice and you fall off the sled, it may be too loud in the running pack for the dogs to hear you yell for them to stop, and they can just run off, leaving you there to die. Dogs have also been known to attack and kill the human rider before. A fun fact is that dogs sometimes need to shit during the ride but the whole thing won’t stop just for that so they have to stop running and poop while their whole body is just dragged along at full speed while this happens.

Greenland dogs are perfectly built for rugged dog-sledding, and to keep them that way, Greenland prohibits dogs of any other kind from being taken above the Arctic Circle for fear that they’d interbreed with the Greenland dogs and ruin the purity of the breed. Likewise, no Greenland dog is allowed to be taken below the Arctic Circle—if it happens, they can never return.

I also got the distinct impression that the dogs were treated much more as equipment than as pets. Everywhere I saw them, they were just kind of sitting there, chained to a post, with no people around. I heard that there are only two veterinarians in the whole country, which suggests that doing anything but shooting a sick or injured dog is a ridiculous concept. Oh, and the laws are pretty strict about keeping your dogs chained up—in one town I visited, every Wednesday between noon and 2pm, a cop drives around and shoots any loose dog he sees.

4) The Word nalunaarasuartaateraliornialersaaraluaranimgooruna

It means lighthouse.

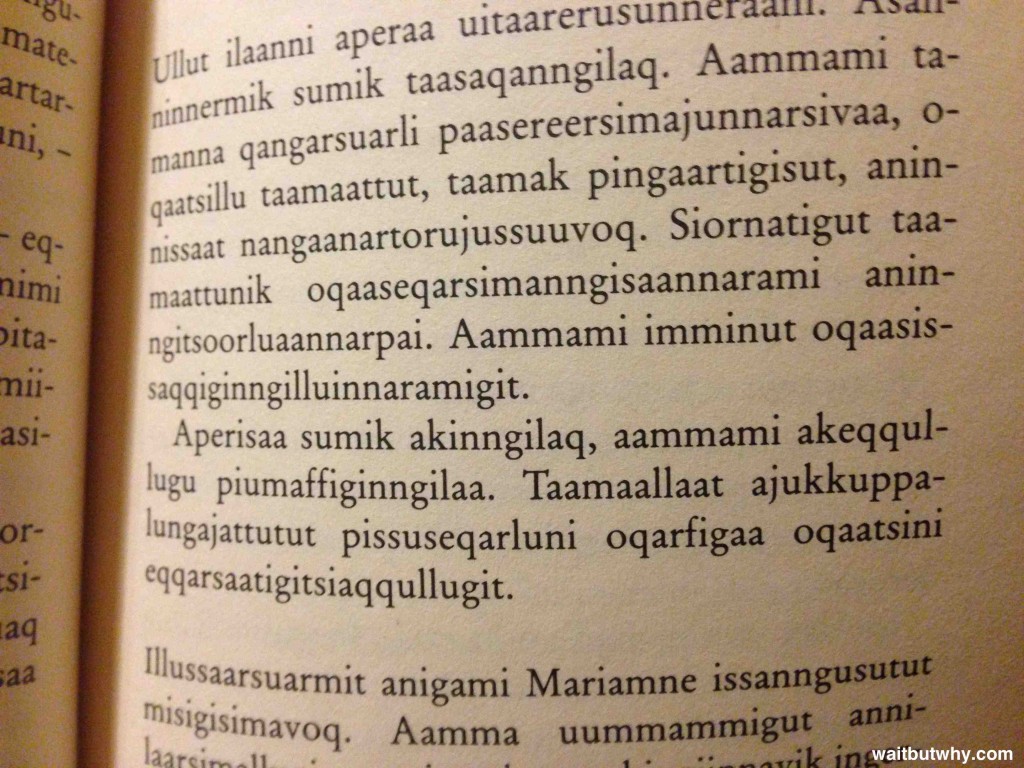

You know how Spanish and Italian are closely related languages and there are a lot of similar words and pronunciation between them? And how Spanish and English also have similarities but they’re more distantly related? And how Spanish and Norwegian are even more distant from each other? And how Spanish and Mandarin are really far away from each other and you will find almost no similarities? Linguistics is like evolution—it’s all related to each other somewhere back in the past, but the farther back the branch-off point between two languages happened, the stranger one language will seem to a speaker of the other.

Well Greenlandic is an Eskimo-Aleut language, which means it’s really, really far away on the linguistics tree from an Indo-European language like English.8

Look at this text. It’s weird, right?

I tried to work on getting some of the pronunciations down for a little before giving up and directing all of my focus to counting the letters in words and trying to find the longest word possible. Lighthouse.

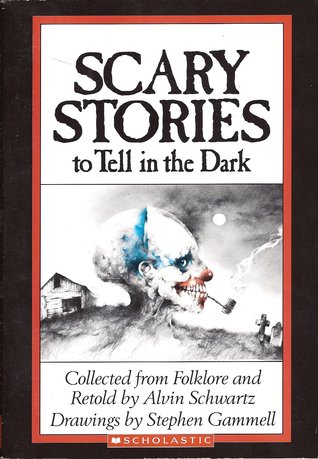

5) Spookiness

I had a hunch I might be going to a spooky place when I booked my Greenland flight, but I didn’t consider that I’d be spending two weeks inside this book:

Here’s the kind of shit that’s going on up there:

- We’ll start with the wolf howls that echo throughout the land.

- Then there was a conversation I had with a Danish guy who has lived there for ten years who said strange or upsetting things happen in Greenland sometimes that the rest of the world never hears about. He didn’t elaborate.

- On the side of the road, you’d see things like this plane wreck with this coke can there in the wreckage.

- A local showed me various crevasses in the Earth along a hiking trail where you can see human skeletons down below who had been buried there.

- A lot of Greenlanders believe in ghosts, and many sleep with the light on because of this fear.

- There are apparently things called qivitoqs in Greenland, that multiple people made sure to tell me about. The legend says that they’re half-dead, half-alive people with the strength of an animal who roam the land at night. One guy told me that they’re actually a real thing—that they’re real people who were either abused when they were younger and ran away or who were exiled from their village, and they spend their lives alone in the wilderness fending for themselves. Those who survive end up very strong, wanting revenge, and are often not in their right mind, and they’re known to reappear in a village after years away and murder people. He said sometimes people will see footprints in the snow outside their isolated home when they know no one in their family had walked there. Ticket back to fucking Iraq please.

- This landed me online looking up homicide rates by country statistics and learning that 24 of the 25 countries with the highest murder rates are all in Latin America and Africa. The other one? Greenland.

- Prisoners are required by law to be in their cells between 9:30pm and 6:00am, but they can leave as they please at all other times.

- Extra unhelpful are the sudden snaps and rumbles in the night that come from icebergs breaking and the wind blowing through huge ground crevasses that often make human-like sounds.

6) Santa

On the flip side, Santa Claus lives in Greenland.

So you know when kids write a letter to Santa and address the envelope to The North Pole and it’s highly inane and that’s that? Well what I’ve now learned is that in many places in the world, those letters are actually shipped somewhere—to a big red mailbox in Ilulissat, a 4,500-person town halfway up Greenland. I didn’t believe it either.

But when I got to Ilulissat and marched straight to where this supposed mailbox was, I was stunned to see not only the mailbox, but through its glass front, thousands of letters to Santa from all over the world.

Things got even crazier when the same guy who told me about the phantom snow footprints told me that a bunch of people in the town volunteer to write letters back to each child, and he was one of them—he was Santa Claus.

I asked him 2,500 questions about this, and learned the following:

- Santa uses Google Translate to write back to kids in whatever language they speak

- All letters are hand-written

- All letters receive a reply

- There were hundreds of pacifiers in the box, which boggled me when I saw them, and he explained that it’s common for parents to coax their kid to quit the pacifier by having the kid “mail it to Santa”

- Danish children aren’t told that Santa lives in the North Pole. They’re told he lives in Greenland. The Danish are the only parents in the Christian world not lying to their children

The Three Days I Was the Domestic Partner of Berthelina, the 72-Year-Old Grandmother of an Entire Greenlandic Town

We might as well end a weird series of posts on a weird note.

I never thought I’d spend three days as Berthelina Inukitsoq’s roommate, and she never thought she’d spend three days as mine. But when I started inquiring about the possibility of visiting a tiny village for a few days, a bunch of weird dominos fell that ended with me doing a homestay with her in a 46-person village called Oqaatsut.

Like all places in Greenland, it’s not easy to get to Oqaatsut. For me, it took two flights and a long boat ride. I finally arrived, here:

An isolated, 46-person town in The Arctic is an intense concept. This became clear right away, when I got to my new home, met Berthelina, and learned that it was her 72nd birthday. What this meant is that she was spending the day being visited by family and friends, so by sitting on the couch for the three hours after I arrived, I met 90% of the city. Not only that, I kept a count of people I met who were Berthelina’s children, children-in-law, or grandchildren, and it was over half of Oqaatsut’s population. I was staying with the town grandmother.

As the residents cycled through the living room, I tried to learn about the town from any of them who spoke a little English. I met Berthelina’s son, a competitive dog-sled racer who had won all the trophies on the shelf. He was also the shopkeeper. And the mayor. And later, when I asked about what happens if there’s a dispute, I learned that he’s also the sheriff. Legit.

His wife was the chef at the village’s restaurant, and his brother, also Berthelina’s son, was one of two village fishermen who supplied the bulk of the village’s food. I learned that it had been a great year for everyone because a few weeks ago, they had caught a whale:

They took a little of the whale for the village and sold the rest of it to 4,500-person Ilulissat.

Also at the party was the town’s teacher, along with both of its students, two teenage girls who really have to make sure they like each other.

The village has a small power station, which provides electricity to the homes, but there’s no plumbing. Sewage is collected by one of the village people every few days and dropped outside the village at a place they’ve designated their dump. There’s running water only in a communal shower house, open at certain specified hours, and drinking water comes by way of melting a little piece of one of the many icebergs floating in the water.9

The low point of the party was me trying to trick a 3-year-old into liking me by showing her a video I took once of a llama eating, except two seconds into the video, she decided I was irrelevant and left, but in those same two seconds, two adults had come over to see the video, so now two adults and I sat there together uncomfortably for 14 seconds while this video played:

Anyway, the party eventually died down, leaving Berthelina and me to confront the fact that we were roommates.

We had no ability to communicate with each other, so we went with Plan B, which was Berthelina giving 0% of a shit either way and me just hanging out near her like her dog. We found a nice groove, and after a little while, she headed up off to bed.

The house suddenly felt kind of creepy with no one else there (remember that I’m already in spooked mode by this point in the trip), so I decided to step outside and one second after I do, this happens:

Nope. I don’t know what that means but nope. So I do a U-turn back inside and head into my bedroom, and I see a bunch of not at all cool drawings lying around on the shelves.

I still don’t know who made those fucking drawings, but by then my psyche was in far too fragile a place to stumble upon them in my silent, dark bedroom. I spent the night alternating between expecting the shadow of a ghost to move by on the wall and expecting the door to burst open and see a qivitoq run in and murder me. Not good times.

The next couple days, aside from a visit to the schoolhouse and an afternoon out with the fisherman watching regretful fish flop around the plastic bin, I spent the meat of my time there shadowing Berthelina as she lived her normal life, listened to her radio, played bingo with her friend, baked muffins twice, cut up a fish, and melted ice blocks. It’s not bad being Berthelina.

Less than a week later, I was back in New York for the first time in almost three months, shocked by almost everything for two days before I immediately became jaded again and re-took everything for granted. And Oqaatsut suddenly seems astoundingly far away.

A three-minute sum-up of my time in Greenland:

The other stops:

Russia

Japan

Nigeria

Iraq

The genie question I asked people in all five countries

And another time, North Korea

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our unannoying-I-promise email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

For new readers: these numbered circles are for extra facts or thoughts or explanations along the way—they’re not for sources normally, so click them if you’re not pressed for time. Anyway, Note 1 is that Greenland is not an independent country—it’s part of the Kingdom of Denmark—but as of recently, it’s considered an “autonomous country,” meaning it functions as an independent country in most ways, just not in every way. In this post, I’ll refer to it as a country.↩

Erik the Red’s son is Leif Erikson, who was actually on his way from Norway to Greenland to introduce Christianity there when he was blown off-course and became the first European to land on the North American continent (which he named Vinland)—500 years before Columbus’s voyage.↩

So you know how you think the word “Eskimo” is old fashioned and derogatory and Inuit is the PC word to use? Well it’s actually more complicated than that. The indigenous people of Greenland, Northern Canada, and part of Alaska are Inuit people, and it’s okay to call them that. But a large portion of native Alaskans are the Yupik people, who are not Inuit, and it’s offensive to call them Inuit. And because Alaska has some Inuit and some non-Inuit, it’s actually preferred that you call them all Eskimos, which can refer to all native Alaskan people. On the other hand, in Northern Canada and Greenland, where the vast majority of people are Inuit, Eskimo is considered offensive. Part of the reason the word carries a negative connotation is that it was believed for a long time that imperialists invented the word and it meant “one who eats raw meat,” and who wants to be called that. In fact, it’s now believed to be derived from an ancient Eskimo-Aleut word which means “one who nets snowshoes,” which is apparently less offensive. Confusing. Just remember—call Alaskans Eskimos and call everyone else Inuit (or if you want to actually be a not dumb person, call them by their real sub-ethnicities—Yupik, Inupiat, etc.—but you and I both know you’re not gonna remember to do that).↩

The US offered Denmark $100 million for Greenland in 1946 and they declined.↩

I did a short post on this once.↩

In 2012, two guys caught a Manhattan-size ice chunk breaking off a Greenland glacier on camera. The largest iceberg ever recorded was the size of Jamaica and broke off Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf in 2000—it took 12 years to melt.↩

While reading about wolves and dogs in my research, I learned that barking makes up only 2.3% of all wolf vocalizations and is considered a rare event. It’s wolf puppies who do most of the barking. Domesticated dogs, though, bark all the time, no matter what age. This is explained as a side product of breeding tameness in dogs—by selecting for tameness, domestication has inadvertently created dogs who act juvenile their whole lives, in the way they’re submissive, their whining, their floppy ears, and the fact that they bark. I heard almost no barks in Greenland because they’re not the kind of dogs I’m used to—they’re wolves.↩

Fun fact: “igloo” and “kayak” are both Greenlandic words adopted by English.↩

At some point, I reazlized this was cool water to be drinking. It was in liquid form for the first time since humans were all hunter-gatherers. It fell on top of the ice sheet as snow over 10,000 years ago and had spent the time since then as ice. Sucks to finally become water again only to have someone drink you immediately.↩