Quick break from the multi-week process of birthing the 700-pound SpaceX baby that’s been growing in my womb for a mini-post to discuss the recent big announcement about the Hyperloop.

The Hyperloop is an Elon Musk brainchild that would bring people from Los Angeles to San Francisco in about a half hour—on the ground. The idea first popped into Musk’s head when California unveiled their plans for a much-hyped “high speed rail” connecting LA to San Francisco. He says:1

When the California “high speed” rail was approved, I was quite disappointed, as I know many others were too. How could it be that the home of Silicon Valley and JPL—doing incredible things like indexing all the world’s knowledge and putting rovers on Mars—would build a bullet train that is both one of the most expensive per mile and one of the slowest in the world?

Musk wasn’t angry at California…just disappointed (which California reports “hurt a lot more actually”). Musk said California was “going for records in all the wrong ways,” building the most expensive public works project in United States history2 ($68.4 billion), one that wouldn’t be finished until 2029, and one that would only go 220 mph, when Japan, China, Italy, and other countries have already built trains that can go faster. Why was the US finally joining the high-speed party and seemingly aiming for mediocrity? Musk had higher aspirations for the US:

The underlying motive for a statewide mass transit system is a good one. It would be great to have an alternative to flying or driving, but obviously only if it is actually better than flying or driving. The train in question would be both slower, more expensive to operate (if unsubsidized) and less safe by two orders of magnitude than flying, so why would anyone use it? If we are to make a massive investment in a new transportation system, then the return should by rights be equally massive. Compared to the alternatives, it should ideally be:

- Safer

- Faster

- Lower cost

- More convenient

- Immune to weather

- Sustainably self-powering

- Resistant to Earthquakes

- Not disruptive to those along the route

Is there truly a new mode of transport—a fifth mode after planes, trains, cars and boats—that meets those criteria and is practical to implement?

That last part is key. Musk wasn’t thinking about a faster train—he was thinking about a new mode of transport entirely.

So he and some of his SpaceX engineers took a few days off from trying to colonize Mars to think from the ground up about what California should be trying to do with their time and money. They came up with what Musk called the Hyperloop and laid out the concept in a now-famous white paper. Here’s how it would work:

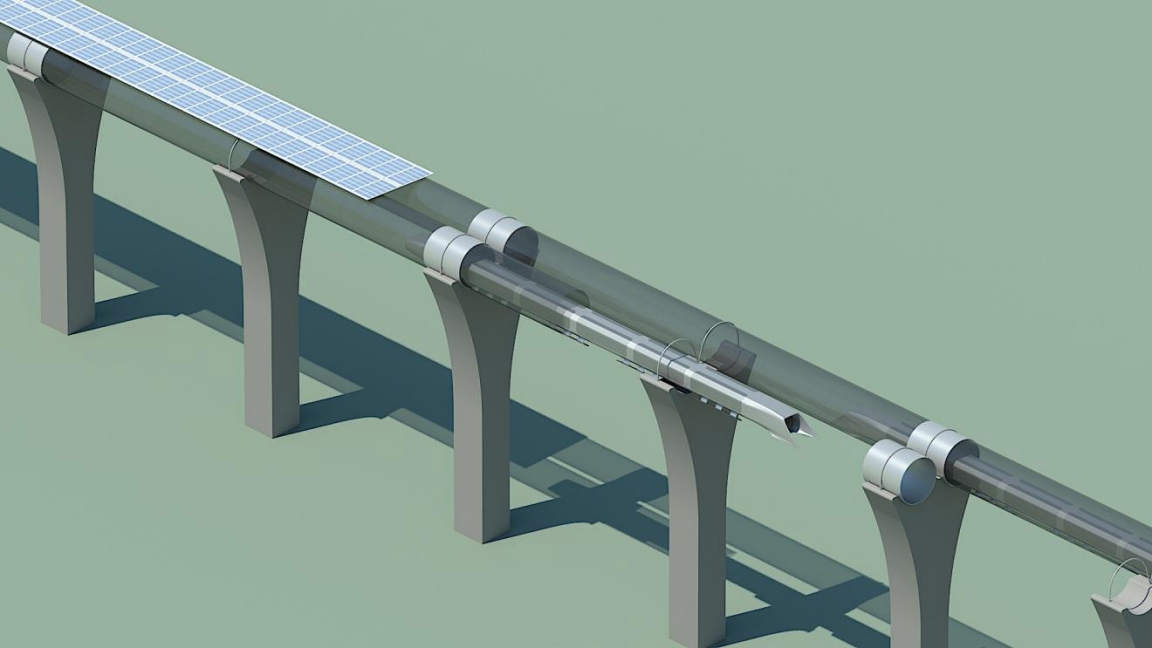

The main body would be a steel tube 7’4″ (2.23m) in diameter, connecting two cities together—in their example, it was LA and San Francisco. The tube would be about 20ft (6m) above the ground, raised up on concrete pylons spaced about every 100ft (30m). Passengers would travel in a small capsule that would hold 28 people. There would be two of these tubes, side by side, so the loop could go in both directions. Here’s a depiction of what it would look like, with the tube cut out over part of it for illustration:

The idea is that the capsule would whiz from LA to San Francisco in only 35 minutes (compared with 3 hours and 10 minutes for the planned CA high-speed railway). It would do this with a top speed of 760mph (1,220km/h), which it would reach during long straightaways. During windier parts, it would go 300mph (483km/h), and the average speed from LA to SF would be 598mph (962km/h).

Propulsion

In figuring out how the Hyperloop would get this fast, Musk and his engineers bumped into a few walls. Traditional wheels and axles were out of the question because they’d be too unstable and inefficient at super high speeds. Pushing the capsule with a column of air (like those tubes used to send mail and packages between buildings) wouldn’t work because the friction would be way too high for a system so big and fast. The vacuum idea was intriguing, but it couldn’t be a total vacuum system, because there would be no way to make such a large system truly airtight.

They ended up finding a potential solution with a near-vacuum chamber that had a small amount of air in it. The capsule would ride on a little cushion of air, kind of like an air hockey table, except the air would be coming out of the puck in this case (the bottom of the capsule), not the table (the tube). To avoid the problem of the air “bunching up” in front of the capsules (like a syringe pushing liquid), pumps on the front of the capsule would direct air from the front of the capsule to the back.

Of course, the whole thing would be solar-powered and electrically-propelled. There would be solar panels on top of the tube, which Musk says would “generate far in excess of the energy needed to operate.” And propulsion would happen in the same way it does for the Model S—electrical induction. In this case, instead of a round, pigs-in-a-blanket motor, you’d have it “rolled out flat” so that there would be stator panels on the inside of the tube which would “push” on rotor panels on the outside of the capsule to fling it forward. These “motors” in the tube (the stator panels) would only need to be in sparse locations. With very little friction, most of the time the capsule would just be gliding on inertia.

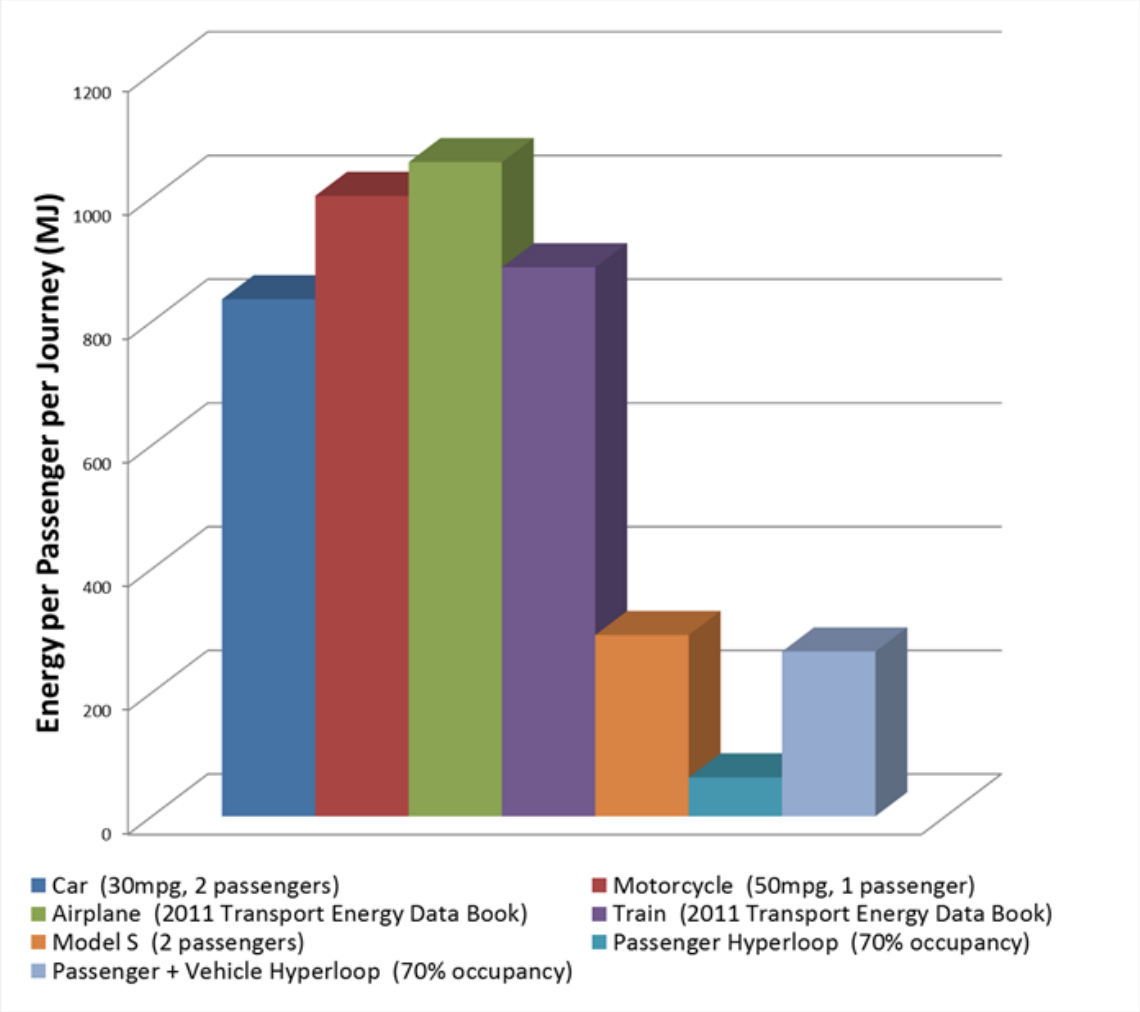

The result would be the lowest energy cost per passenger in history to get people from LA to SF:

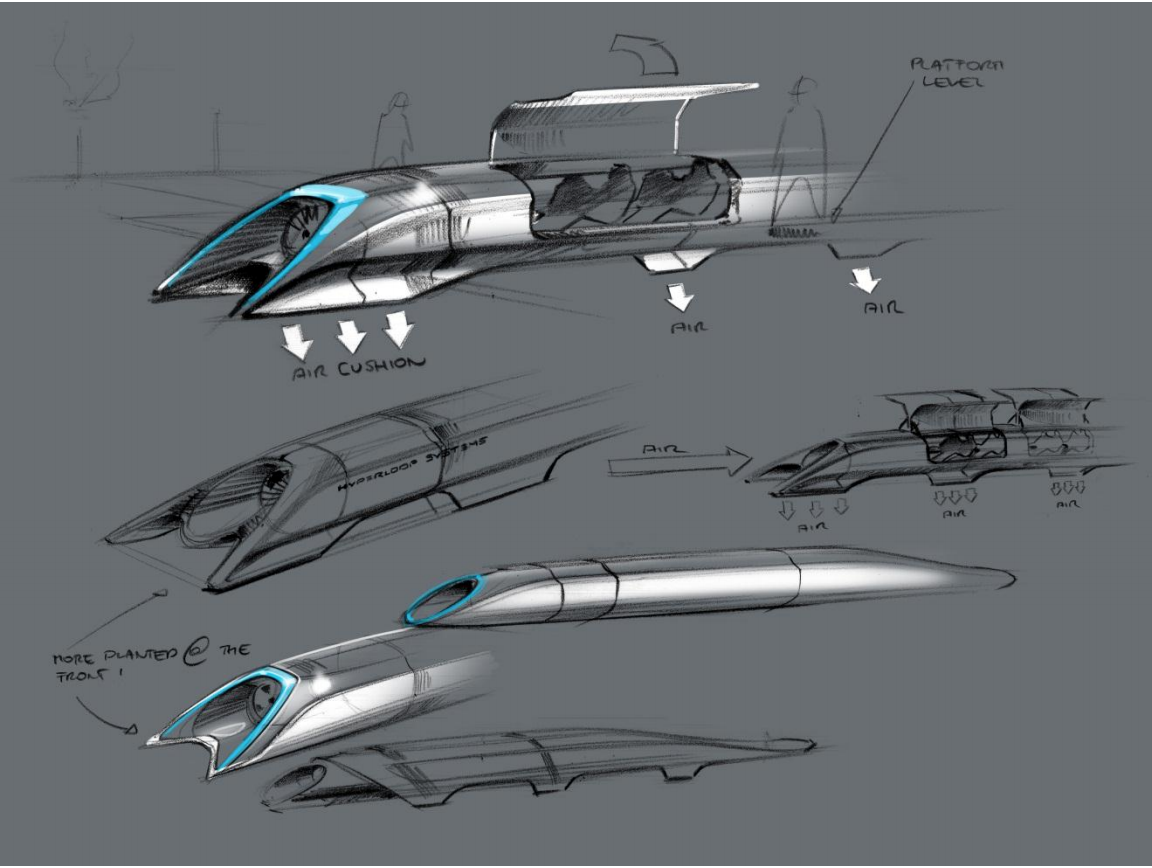

The capsule itself would need to be small—4.43ft (1.35m) wide and only 3.61ft (1.10m) high. No standing room. Here were some early sketches of the capsule, included in the white paper:

The inside would be two columns of 14 seats:

There would be no windows (no point with a steel tube surrounding the capsule) but Musk says that “beautiful landscapes” would be displayed inside the cabin, and that each passenger would have their own entertainment system.

It’s About Commuting

The purpose of the Hyperloop wouldn’t be to make taking vacations easier. It would mostly be a method of commuting—i.e. people living in LA could now get a job in SF as easily as they could in LA, or vice versa. One version of the envisioned Hyperloop only carries passengers, but the white paper also laid out a possible second version, which would be able to carry three full-size cars as well. So someone could drive right onto the capsule in LA, hang out in their car for 35 min, and then drive out in San Francisco.

The whole system would have 40 capsules. Each would be on a continuous 80-minute loop of 35 min from LA to SF, 5 min at the SF station, 35 min back to LA, 5 min at the LA station, and repeat. 40 capsules each on an 80-minute loop means capsules depart every two minutes. This would be plenty to achieve the goal of 840 total passengers commuting back or forth per hour, which would easily accommodate the 6 million passengers that travel between LA and SF each year.

Routes

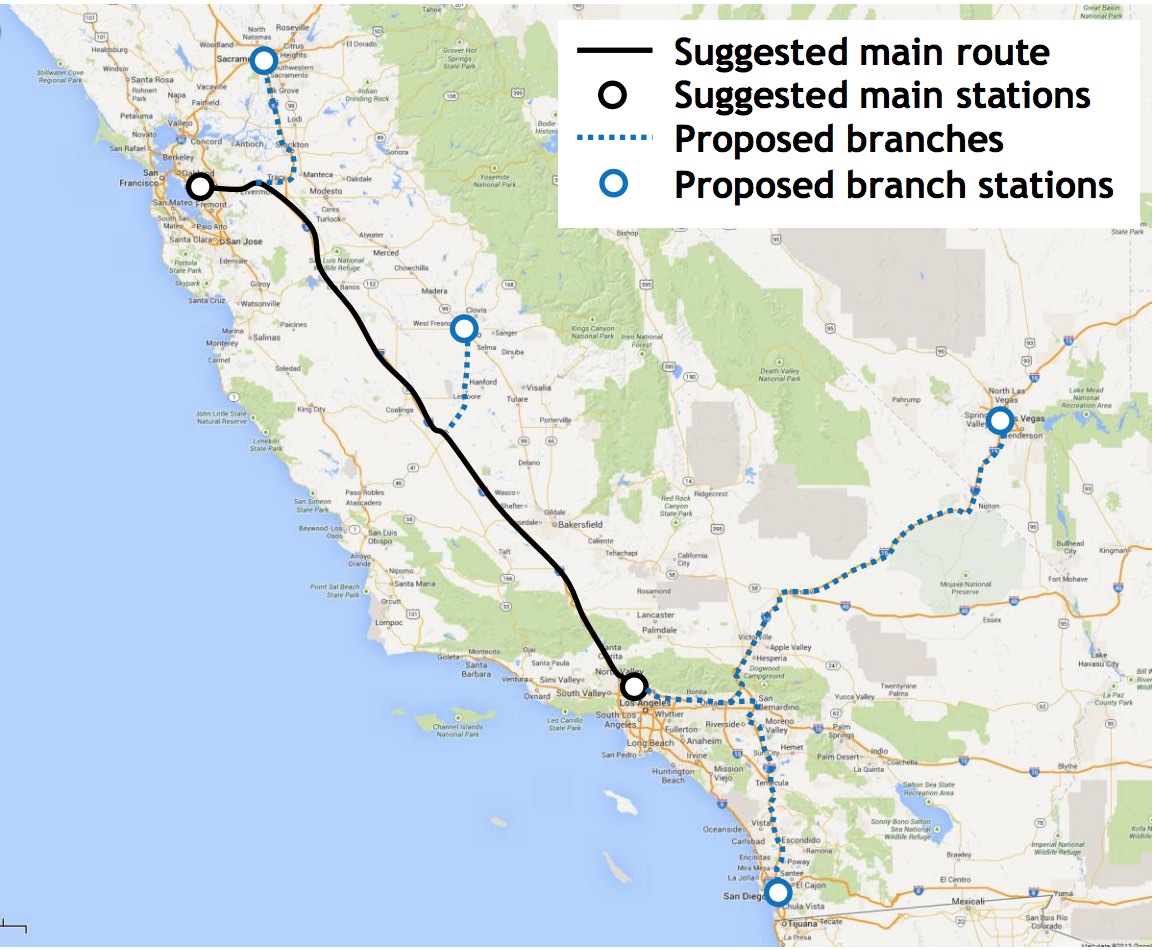

The white paper focuses on LA to SF, and there could be several splits in the tube along the way to service multiple stations:

Unlike California’s planned high-speed railway, the Hyperloop wouldn’t take up much existing land—because it would be built right into the I-5 median (the I-5 is the major highway connecting LA and SF).

Musk thinks Hyperloop-type transport should connect places that are less than 900 mi (1,500 km) apart. He believes the long-term future of air transport will be electrically powered, high-altitude, supersonic planes, and that that type of air travel will be faster and cheaper than a Hyperloop for distances longer than 900 miles. But when the distance is shorter, Musk says that “having a supersonic plane is rather pointless, as you would spend almost all your time slowly ascending and descending and very little time at cruise speed.”

Cost

In the white paper, Musk breaks down the expected cost of building the Hyperloop and comes to a figure of $6 billion ($7.5 billion for the version that can carry cars). The bulk of this cost is the tube, while the capsules are relatively cheap to build. If Musk is anywhere near correct, that would be significantly cheaper than the $68.4 billion California high-speed rail. Cheaper building costs means cheaper ticket prices, and Musk estimates the cost of a one-way trip on the Hyperloop at $20.

Criticism

Unsurprisingly, not everyone is sold on the Hyperloop. Many have scoffed at Musk’s cost estimates—the Economist says the estimates are “unlikely to be immune to the hypertrophication of cost that every other grand infrastructure project seems doomed to suffer.” Others have raised eyebrows at Musk’s description of the silent, smooth, pristine experience for passengers, wondering if riding in a windowless cabin with no standing room might be more like hell. As far as the LA-SF route, there’s also the little matter of the California high-speed railway plans and the fact that they’re already very much underway—it will be a political nightmare to try to get the state to abort the mission.

A Spark

The thing about Musk’s Hyperloop idea and the white paper is that they’re not actual designs for execution—they’re a glimpse at what we could do. I’m sure Musk would love to take on the project himself, but he says he’s too committed to Tesla and SpaceX to do it right now anyway. What he wants is to remind people of what’s possible and to spur innovation in others.

That became a reality when, inspired by Musk’s white paper, a group of engineers, designers, architects, and contractors came together to form Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, a crowd-funded company with a mission to make the Hyperloop a reality. Their first crack will be to connect LA with Las Vegas (using the route along the highway I-15), something they predict can be finished by 2025, four years before the CA high-speed railway is complete.

To further accelerate Hyperloop innovation, SpaceX recently launched the SpaceX Hyperloop Pod Competition, “geared towards university students and independent engineering teams, to design and build the best Hyperloop pod.” SpaceX is building a one-mile test track at the SpaceX headquarters in LA, and teams will get to demonstrate their prototypes on the track one year from now, in June 2016.

This is their delicious 13-second ad for the competition:

Who knows if the Hyperloop will become a reality or not, but this is another example of Elon Musk pushing humanity to its limits and reminding us not to settle for unnecessary mediocrity. Let’s hope someone can make it work, because I’d love to live in a Hyperloop future where I can head to work in New York in the morning, zip out around noon to have a 12:45 lunch with my dad in Boston, finish up the work day in New York, catch an 8pm baseball game in DC, and be in my bed in New York by midnight.

___________

This was a mini-post that’s part of a larger series on Elon Musk and his companies:

Part 1: Elon Musk: The World’s Raddest Man

Part 2: How Tesla Will Change the World

Part 3: How (and Why) SpaceX Will Colonize Mars

Part 4: The Cook and the Chef: Musk’s Secret Sauce

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our unannoying-I-promise email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

Unless otherwise noted, all facts, figures, images, and quotes in this post are from this 2013 white paper Musk wrote about the Hyperloop.↩

http://theweek.com/articles/540002/most-expensive-publicworks-project-history↩